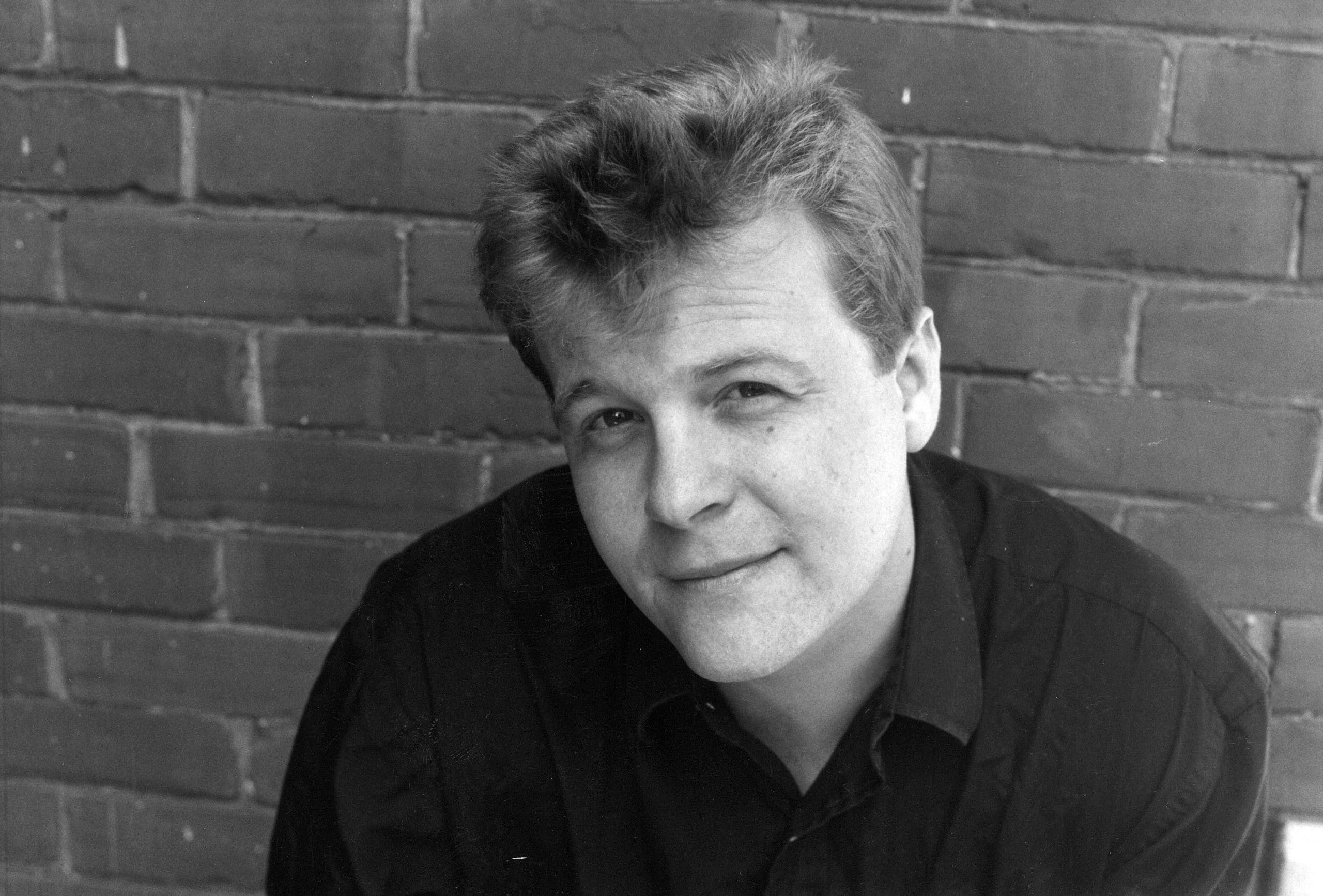

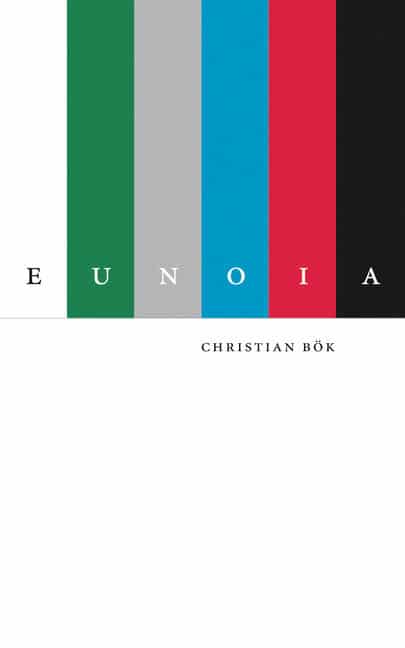

Christian Bök is a Canadian poet, essayist, and professor renowned for his experimental approach to language and poetry. Born in 1966 in Toronto, he is the author of several books that push the boundaries of language and poetic invention, including his acclaimed book Eunoia (Coach House Books, 2001), which won the 2002 Griffin Poetry Prize.

Bök’s other notable works include Crystallography (Coach House Books, 1994), a pataphysical encyclopedia nominated for the Gerald Lampert Award for Best Poetic Debut, Pataphysics: The Poetics of an Imaginary Science (Northwestern University Press, 2001), and The Xenotext, a long-term project that aims to encode a poem into the DNA of a bacterium.

Nature has interviewed Bök about his work on The Xenotext (making him the first poet ever to appear in this journal of science). Bök has exhibited artworks derived from The Xenotext at galleries around the world; moreover, his poem from this project has hitched a ride, as a digital payload, aboard a number of probes exploring the Solar System (including the InSight lander, now at Elysium Planitia on the surface of Mars).

In addition to his literary work, Bök’s conceptual artwork has appeared at the Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York City as part of the Poetry Plastique exhibit. He has also created artificial languages for the TV shows, Gene Roddenberry’s Earth: Final Conflict and Peter Benchley’s Amazon. Bök has also earned many accolades for his virtuoso performances of sound poetry (particularly the Ursonate by Kurt Schwitters).

Bök is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and he teaches at Leeds School of Arts in the U.K.

Judges’ Citation

Christian Bök has made an immensely attractive work from those ‘corridors of the breath’ we call vowels, giving each in turn its dignity and manifest, making all move to the order of his own recognition and narrative.

Selected poems

by Christian Bök

Enfettered, these sentences repress free speech. The

text deletes selected letters. We see the revered exegete

reject metred verse: the sestet, the tercet – even les

scènes élevées en grec. He rebels. He sets new precedents.

He lets cleverness exceed decent levels. He eschews the

esteemed genres, the expected themes – even les belles

lettres en vers. He prefers the perverse French esthetes:

Verne, Péret, Genet, Perec – hence, he pens fervent

screeds, then enters the street, where he sells these let-

terpress newsletters, three cents per sheet. He engen-

ders perfect newness wherever we need fresh terms.

Relentless, the rebel peddles these theses, even when

vexed peers deem the new precepts ‘mere dreck.’ The

plebes resent newer verse; nevertheless, the rebel per-

severes, never deterred, never dejected, heedless, even

when hecklers heckle the vehement speeches. We feel

perplexed whenever we see these excerpted sentences.

We sneer when we detect the clever scheme – the emer-

gent repetend: the letter E. We jeer; we jest. We express

resentment. We detest these depthless pretenses – these

present-tense verbs, expressed pell-mell. We prefer

genteel speech, where sense redeems senselessness.

Copyright ©2001 by Christian Bök, Eunoia, Coach House Books

from “Chapter E”

Writing is inhibiting. Sighing, I sit, scribbling in ink this pidgin script. I sing with nihilistic witticism, disciplining signs with trifling gimmicks — impish hijinks which highlight stick sigils. Isn’t it glib? Isn’t it chic? I fit childish insights within rigid limits, writing schtick which might instill priggish misgivings in critics blind with hindsight. I dismiss nitpicking criticism which flirts with philistinism. I bitch; I kibitz – griping whilst criticizing dimwits, sniping whilst indicting nitwits, dismissing simplistic thinking, in which philippic wit is still illicit.

Copyright ©2001 by Christian Bök, Eunoia, Coach House Books