Karen Solie’s first collection of poems, Short Haul Engine, won the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize and was shortlisted for the 2002 Griffin Poetry Prize, the ReLit and the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award. Her second, Modern and Normal, was shortlisted for the Trillium Book Award for Poetry. Her poetry, fiction and non-fiction have appeared in numerous North American journals. She is a native of Saskatchewan and now lives in Toronto.

- 2010

- 2002

Judges’ Citation

Karen Solie’s first book of poems, Short Haul Engine – a nice phrase for poetry – stood out for its mix of physical impressions, perceptual strength, and – especially – mental grace.

Judges’ Citation

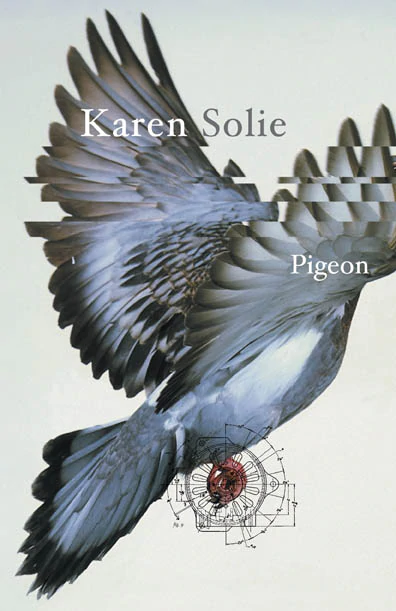

Among the greatest of Solie’s talents, evident throughout the poems of Pigeon, is an ability to see at once into and through our daily struggle, often thwarted by our very selves, toward something like an honourable life.

Selected poems

by Karen Solie

It was the summer some rank fever weed

sunk her bitch hooks in, sowed my skin

to itch and ooze, that we shared a bed

for the first time. It’s not so bad,

you said, looking for a clean place

to put your hands while I stuck to the sheets

and stunk up the room with creams

and salves. You didn’t cringe,

(though in those days my back was often turned)

took your showers at the usual time, rose,

a bank of muscled cloud above

my poisoned field, and blew cool

across the mess. I said, eyes shining

with antihistamines, that you were potent

as a rare bird sighting, twenty on the sidewalk,

straight flush. It was only falling

into sleep that your body twitched away

from mine, a little more each time

I’d scratch, and I knew then we were made

for each other, that you lie as well as me,

my faithful drug, my perfect match.

Copyright © Karen Solie 2001

Anniversary

It seemed needlessly cruel

that I couldn’t coax even the hardiest,

homeliest, dullest of plants to grow

in the one west-facing window

of that place, with its air conditioner, sealed

with duct tape, that didn’t work,

and its mouse-hole, stuffed with steel

wool, that did. And an equally

needless kindness even more

unbearable, that unexpected flowering

inside the cheap circumference

of the pot while I was nearly

bedridden, of seeds borne on a broad wind

that flew in, and volunteered.

Copyright © 2009 Karen Solie

Geranium

Night blind through Rogers Pass,

engine popping like a rabbit gun

after an ambush of tunnels,

I brake for tinfoil, bottles,

dead stares of twisted deer.

This moon-shot boneyard

is a seam of eyes.

Immigrant rail crews lost

to the slides of March

a century ago. Two Japanese dug out

clasped in each other’s arms,

a Norwegian frozen in the act

of filling his pipe. No time

even to bruise.

Hidamo. Wafilsewki. Mitsumi. Sodiatis. Sanquist.

Bronze and marble statues

for the meat ride to Glacier Station.

And the whores who died cold,

full of holes, in clapboard Columbia

or the pockmarked skin village

of Golden. A drunken doctor drowned

in a puddle of horse piss.

Years later, slide shooters

and dozers shoved 92 miles of highway

through the Selkirks’ seismic muscle,

and now my four seizing cylinders

whine for a tail wind

to Saskatchewan. I Go All The Way,

Number One croons

over archival mutterings caught

in the black throat of the old Connaught Tunnel

buried at the Summit. Accordian ballads

of accidents that wait to happen

in the rock face, snow

fall, concentrated gravity of the gorge.

My odometer books odds of sleep

in hands and head. The cat knows it,

moving through luggage in the back seat,

throwing sparks.

Copyright © Karen Solie 2001.

In Passing

Above, blue darkens as it thins to an airlessness wheeling

with sparkling American junk

and magnetic brains of astronauts. We are flung

across our seats like pelts.

Some of us are eating small sandwiches.

Some of us have taken pills and are swallowing

glass after glass of gin.

We were never intended to view the curve of the earth

so they give us televisions, a film

about a man and his daughter who teach a flock

of Canada geese to fly.

Wind shear hates the sky and everything in it,

slices at right angles across the grain of currents

like a cross-cut saw.

Fog loves surprises.

We have fuel, fire, Starbuck’s coffee, finite

possibilities of machinery. A pilot with human hands

and nothing for us to do, turbulence being to air

what hope is to breathing.

A property.

Far below, a light comes on in the kitchen of a farmyard

turning with its piece of the world into shadow.

Someone can’t sleep

an engine noise falls around the house like snow, vapour trails

pulled apart by frontal systems locked overhead

since high school. Imagines

alien weathers that unfurl in time zones

beyond the horizon.

Copyright © Karen Solie 2001.

In-Flight Movie

for Cathy

Snow is falling, snagging its points on frayed

surfaces. There’s lightning

over Lake Ontario, Erie. In the great central

cities, debt accumulates along baseboards

like hair. Many things were good

while they lasted. Long dance halls

of neighbourhoods under the trees,

the qualified fellow-feeling no less genuine

for it. West are silent frozen fields and wheels

of wind. In the north, frost is measured

in vertical feet, and you sleep sitting because it hurts

less. It’s not winter for long. In April

shall the tax collector flower forth, and language

upend its papers looking for an entry adequate

to the sliced smell of budding

poplars. The sausage man will contrive

once more to block the sidewalk with his truck,

and though it’s illegal to idle one’s engine

for more than three minutes, every one of us will idle

like hell. After all that’s happened. We’re all

that’s left. In fall, the Arctic tern will fly

12,500 miles to Antarctica as it did every year

you were alive. It navigates by the sun and stars.

It tracks the earth’s magnetic fields

Sensitively as a compass needle and lives

on what it finds. I don’t understand it either.

Copyright © 2009 by Karen Solie, Pigeon (House of Anansi Press)

Migration

They stayed at home. They didn’t go far.

Trends do not move them.

From picture windows of family homes

they cast wide gazes of manifest pragmatism:

hopeful and competent, boundlessly integrated,

fearless, enviable, eternal.

Vegas, Florida, Mexico, Florida, Vegas.

With children they travel backroads

in first and last light to ball fields

and arenas of the Dominion.

We have no children. We don’t own,

but rent successively, relentlessly,

to no real end. The high-school reunion

was a disaster. Our husbands got wasted

and fought one another, then with an equanimity

we secretly despised, made up over

anthem rock, rye and water. Our

grudges are prehistoric and literal.

It seems they will survive us. The girls

share a table, each pitying the others their looks,

their men, their clothes, their lives.

Copyright © 2009 Karen Solie