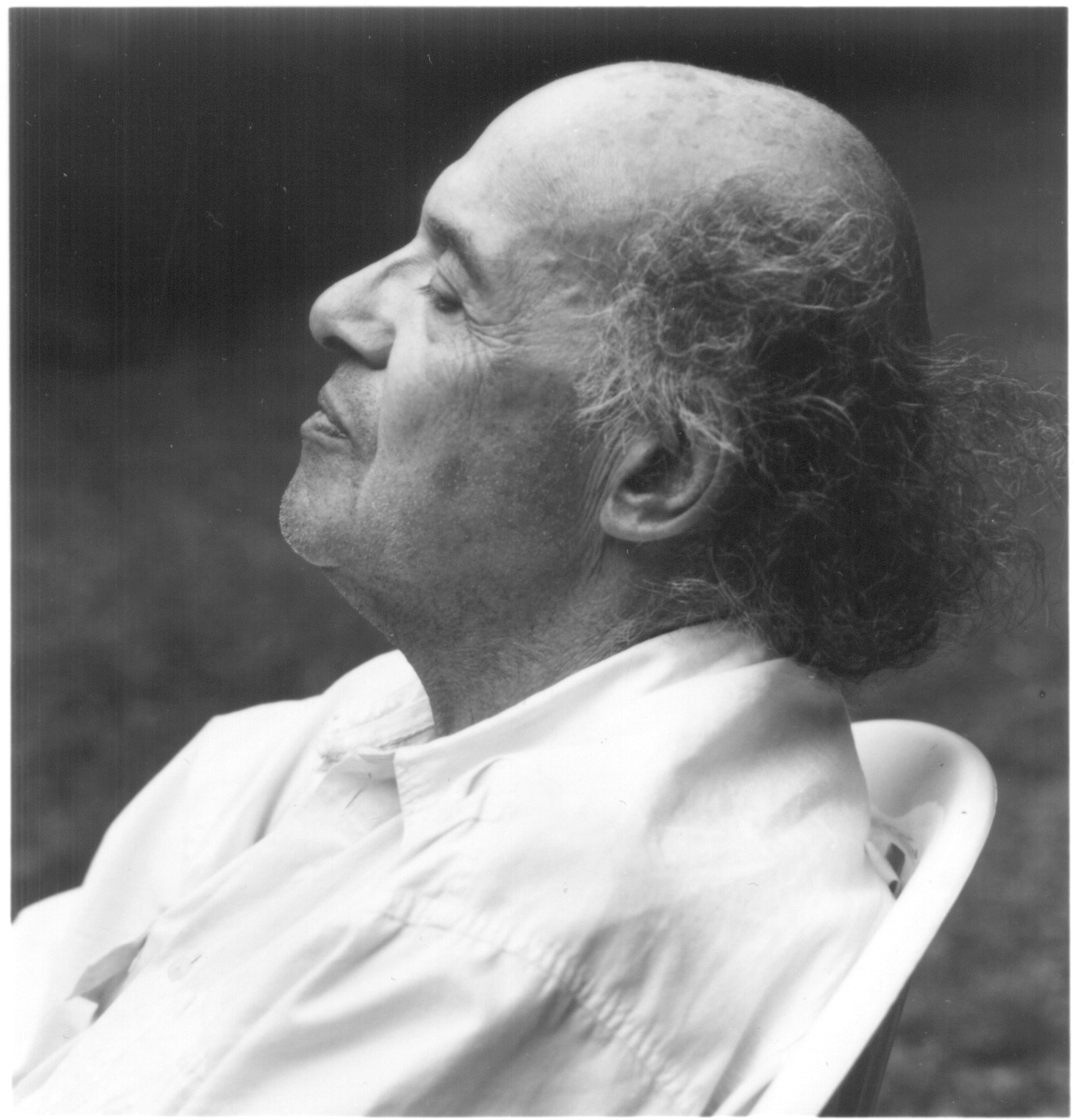

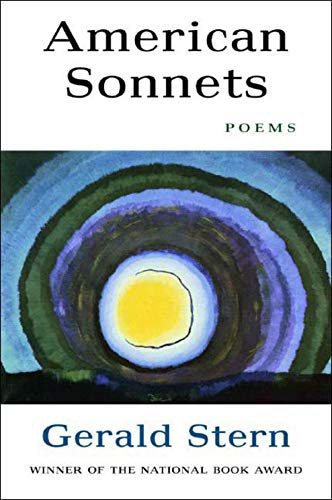

Gerald Stern is the author of numerous books of poetry, most recently Everything is Burning. Among his many honors are the Lamont Prize, the National Book Award, a Guggenheim fellowship, three NEA awards, a fellowship from the Academy of Arts and Letters, and the Ruth Lilly Prize. Stern taught at the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa until his retirement in 1995, and has served as a member of the faculty at Columbia University, New York University, Sarah Lawrence College, and the University of Pittsburgh. Today he lives in New Jersey and continues to write both poetry and prose.

See also: Griffin Trustee Robin Robertson, Griffin Poetry Prize 2004 shortlisted poets Leslie Greentree and David Kirby, and Griffin Poetry Prize 2003 shortlisted poet Gerald Stern were joined by the 2005 Canadian and International winners Roo Borson and Charles Simic on a triumphal tour to the Dublin Writers Festival in June, 2005. Leslie, David and Roo kept a lively blog of the trip, which you can read here.

Judges’ Citation

Gerald Stern’s poems are astonishing; they have profound suppleness, tenderness, and power.

Gerald Stern’s poems are astonishing; they have profound suppleness, tenderness, and power. When we finish one of these American sonnets, we laugh or cry out loud, incredulous. Each one seems to begin in pure freedom, then the last line, like a magnet, turns out to have been pulling the whole poem toward itself with the momentum of history and eros. The work is both intimate and inclusive, and the implied reader seems to be unusually present to the speaker’s spirit! The poems are alive with passion and with ironic energy, an irony so in love with the earth it seems to need a new name – milk and honey irony – and yet the tragic knowledge of the world here is hard as iron. This is the great art of a fierce mourning ecstatic, whose genius nourishes us.

Selected poems

by Gerald Stern

When I fought the dog we almost danced

we loved each other that much and he was strong,

not counting even his teeth and claws, and I had

trouble pushing against him even though his

shoulders were weaker in that position nor was he

intended, as Aristotle might say, for fighting

standing up like that the way maybe a

bear was more intended or certainly an

ape with his gross imitation of a

human, or a human of him, if I can

step into that muck a minute, and he was

taller than me, as I remember, which made him

huge for a dog and made me feel small standing

on two legs with my weak left knee impaired

as it was and smelling his breath and shocked by his giant

head and what had to be a look I never

expected in his eyes, though I had to know

it would be like that for who was I anyhow

to bicker as I did or think that love

as I called it, all I did for him, the food

and water I gave him I could barter, I couldn’t

even find my pocket, I couldn’t take out a dollar.

Copyright © Gerald Stern, 2002

All I Did For Him

I had to see La Bohème again just to

make sure for there was a little part of

me that kept the regret though when I tried

the argument again I used both hands

in order to explain and I was especially

sensitive to the landlord for I lived

both inside and outside even when I was angry

I paid my debts for I have listened to

and lived with grasshoppers and they bore me, but

Mimi, Mimi, when your hand dropped every

woman in my row was weeping and I

gave in too instead of gripping the armrest

or rubbing the back of my head; I loved it the most that

you lived inside and outside too, the snowdrop

was what you thought of, wasn’t it? You were

the one who came back, three times, it was your stubbornness,

your loyalty. One time I stood in the street

and watched a moon so thin the clouds went through it

as if there were no body, as if the cold

was so relentless nothing could live there, you with

the blackened cancle, you who stitched the lily.

Copyright © Gerald Stern, 2002

Mimi

What was I thinking of when I threw one of my

peach stones over the fence at Metro North,

and didn’t I dream as always it would take

root in spite of the gravel and the newspaper,

and wasn’t I like that all my life, and who isn’t?

I thought of oranges and, later, watermelon

and yellow mangoes hanging from sweetened strings,

but it was peaches, wasn’t it, peaches most of

all I thought about and if the two trees that

bore such hard little fruit would only have lived

a few years more how I would have had a sister

and I would have watched her blossom, her brown curls

her blue eyes, though given her family she would have

been wild and stubborn, harsh maybe, she would

be the angry one — how quiet I was — the Chinese

grew their peaches for immortality — the

Russians planted theirs so they could combine

beauty and productivity, that was

my aesthetic too, I boiled my grape leaves,

I ate my fallen apples, loving sister.

Copyright © 2002, Gerald Stern

Peaches

The thing about the dove was how he cried in

my pocket and stuck his nose out just enough to

breathe some air and get some snow in his eye and

he would have snuggled in but I was afraid

and brought him into the house so he could shit on

the New York Times, still I had to kiss him

after a minute, I put my lips to his beak

and he knew what he was doing, he stretched his neck

and touched me with his open mouth, lifting

his wings a little and readjusting his legs,

loving his own prettiness, and I just

sang from one of my stupid songs from one of my

vile decades, the way I do, I have to

admit it was something from trains. I knew he’d like that,

resting in the coal car, slightly dusted with

mountain snow, somewhere near Altoona,

the horseshoe curve he knew so well, his own

moan matching the train’s, a radio

playing the Inkspots, the engineer roaring.

Copyright © Gerald Stern, 2002