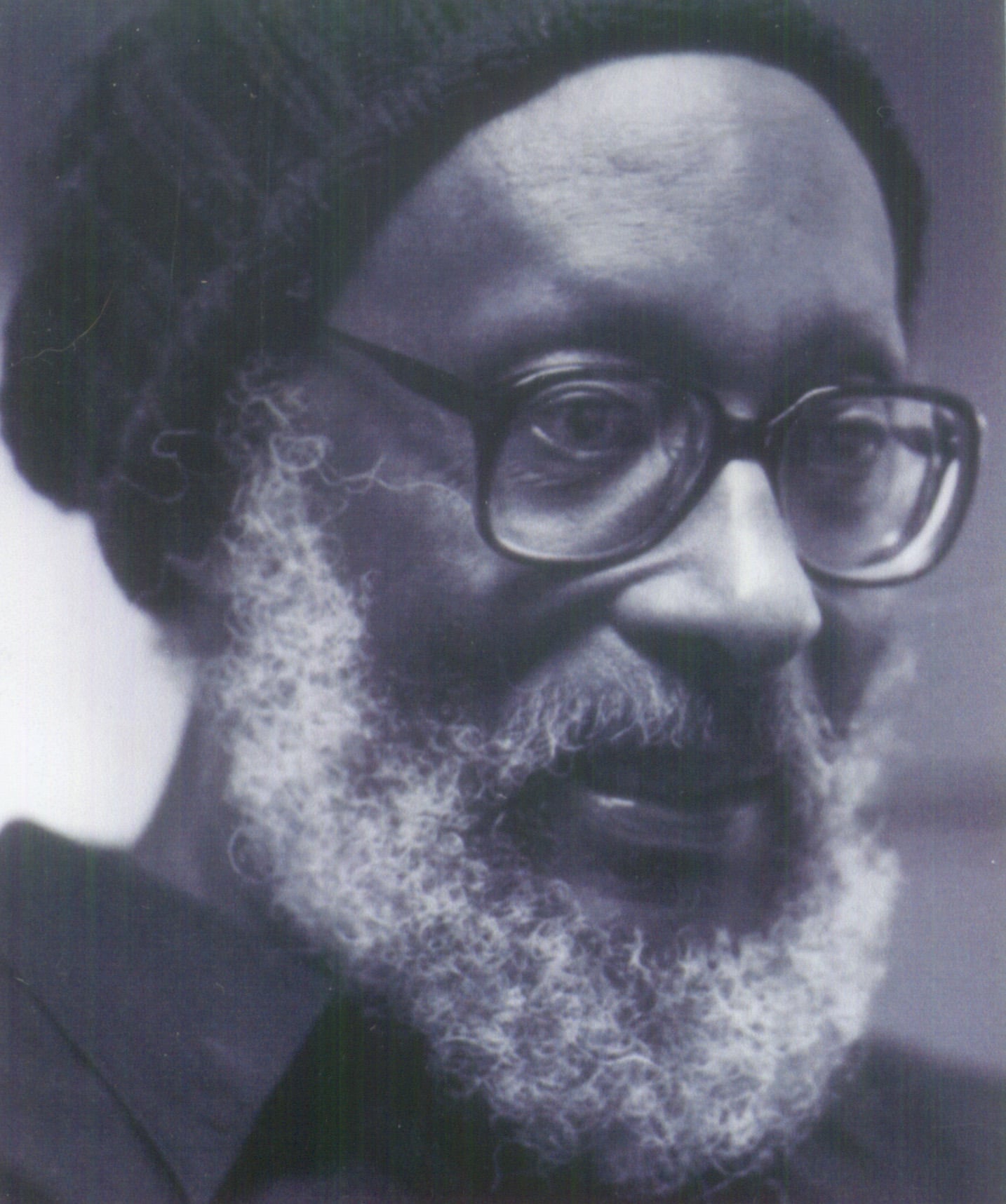

Kamau Brathwaite, born in Barbados in 1930, is an internationally celebrated poet, performer, and cultural theorist. Co-founder of the Caribbean Artists Movement, he was educated at Pembroke College, Cambridge and has a PhD from the University of Sussex in the UK. He has served on the board of directors of UNESCO’s History of Mankind project since 1979, and as cultural advisor to the government of Barbados from 1975-1979 and again since 1990. Brathwaite has received numerous awards, among them the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, the Bussa Award, the Casa de las Américas Prize, and the Charity Randall Prize for Performance and Written Poetry. He has received Guggenheim and Fulbright fellowships, among many others. His book, The Zea Mexican Diary (1992) was The Village Voice Book of the Year. Brathwaite has authored many works, including Middle Passages (1994), Ancestors (2001) and The Development of Creole Society, 1770-1820 (2005).

Over the years, he has worked in the Ministry of Education in Ghana and taught at the University of the West Indies, Southern Illinois University, the University of Nairobi, Boston University, Holy Cross College, Yale University and was a visiting fellow at Harvard University. Brathwaite is currently a professor of comparative literature at New York University. He divides his time between CowPastor, Barbados and New York City.

We were saddened to learn of Kamau Brathwaite’s passing in February, 2020. As tributes pour in acknowledging Brathwaite, his work and his accomplishments, Barbados Today offers these moving reflections.

Judges’ Citation

To read Kamau Brathwaite is to enter into an entire world of human histories and natural histories, beautiful landscapes and their destruction, children’s street songs, high lyricism, court documents, personal letters, literary criticism, sacred rites, eroticism and violence, the dead and the undead, confession and reportage.

Selected poems

by Kamau Brathwaite

And so this foreday morning w/out light or choice

i cannot swim

the stone, i can’t hold on to water, so i drown

i swallow left, i turn & fall-

ow into fear & blight, a night so deep it make you turn

& weep the line of spiders of yr future you see spinn-

ing here, their silver

voice of tears, their lid. less jewel eyes .

all thru this buffeting eternity i toss i burn

and when i rise leviathan from the deep . black shining from my skin

of seals, blask tooth, less pebbles mine the shore

haunted by dust & bromes . wrist, watches w/out tone or tides, communion

w/out broken

hands, x-

plosions of frustration, the trans-

substantiation of the sweat

of hate, the absent ruby lips

upon the wrinkle rim

of wine . i wake to tick

to tell you that in these loud waters of my land

there is no root no hope no cloud no dream no sail canoe or dang, le miracle .

good day cannot repay bad night. our teeth snarl snapp-

ing even at halp-

less angels’ evenings’ meetings’ melting steel

in this new farmer garden of the earth’s delights

this staggering stranger of injustices

come rumbelling down the wheel and grave-

yard of the wind, down the scythe narrow streets, clear

air for a moment. clear

innocence whe we are running. so so so so so many. the crowd flow-

to tell you that in these loud waters of my land there is no root no hope no cloud no dream no sail canoe or dang, le miracle . good day cannot repay bad night. our teeth snarl snapp- ing even at halp- less angels’ evenings’ meetings’ melting steel in this new farmer garden of the earth’s delights this staggering stranger of injustices come rumbelling down the wheel and grave- yard of the wind, down the scythe narrow streets, clear air for a moment. clear innocence whe we are running. so so so so so many. the crowd flow-

ing over Brooklyn Bridge. so so so many . i had not thought death

had undone so many melting away into what is now sighing . light

calp from the clear avenue forever

our souls sometimes far out ahead already of our surfaces

and our life looking back

salt. as in Bhuj. in Grenada. Guernica. Amritsar. Tajikistan

the sulphur-stricken cities of the plains of Aetna. Pelée, ab Napoli & Krakatoa

the young window-widow baby-mothers of the prostitutes .

looking back looking back as in Bosnia, the Sudan. Chernobyl

Oaxaca terremoto incomprehende. al’fata el Jenin. the Bhopal

babies sucking toxic milk, our growing heavy furry tongues

accustom to the what-is-the-word-that-is-not-here-in-English beyond ashadenfreude

not at all like fado or duende

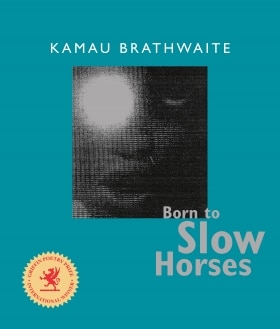

Copyright © 2005 by Kamau Brathwaite, Born to Slow Horses, Wesleyan University Press

from “Hawk”

the 21 days

on the first day

of yr death it is quiet it is dormant like a doormat

no one-foot touch its welcome. its dust on the floor

is not disturb nor are the sleeping spirits of this house

i sit here in this chair trying to unravel Time so that it wouldn’t happen twine

on the second day

of yr death. i break a small

bread

i can still smell the sweet flour of yr firstborn flesh

on the third day

of yr death. the water in my urine turn to blood

i cover the waterfront of the mirror w/a blue cloth where yr face stood

on the fourth day

yu shd be rising. knocking at the door of

darkness. coming back to me

i do not hear yr call

on the fifth day

after yr death. a young white rooster. white white white feathery & shining tail & tall

neigbour of sound from miles away in the next village

stands in the yard & from his red crown crows & crows & will not go away

he struts round to the back-a-wall

his one eye clicking as he crows

comes to the glissen of my window & he crows

loud like the overflowing voice of my Trelawny waterfall

on the sixth day

after yr death. there is this silence of flowers

their petals say their shining needs

soft water needs

sweet showers needs

sweet rain from heaven

•

i see them once again inside the chapel of my funeral

on the seventh day

after yr death. the yellow flour

in the cup-cakes in the kitchen have gone sour

there is an eye of rancid in the middle of their meal

i am unhappy like the wind & tides are restless rivers

i can’t find you. i can’t find you. i cannot cannot cannot be console to dreams

the mad dogs of the pasture kill the cock & pillage

it. madwoman wind is scattering white screaming feathers’ petals’ pedals over all

the brunt and burnin ochre-colour land

on the eiate day

after yr death

me do nothin. nothin. nothin . i cdn’t even get yr inglish ‘eighth’ spelt streight

on the nine / ff night

yu rise again from off the dead

•

i see you now & at the hour of yr o not soff not soffly dead

it is my pain it is my privilege . it is my own torn flesh torn fresh

o let me comfort us my chile . is not yr heart is broken

on this tenth day

i haffe go down to the Station today to find out

what they doin about yr det. about the ‘accident’

dem call it. bout the black-hearted man who a-kill

yu. an whe dem hide yu body

and po. lice who dealin w/ this case they cannot look me in the lips

and No One kno

whe the boy is or gone or when he will come-back

ten time dis ten dem mek me up & down & book & fourt

to fine my sun. an ten ten time dem ave no ansa for me for me for me

in dis dry-weatha tunda

dem seh because i poor & have no book to haul-out

inside dis station. an i inn got no song

to sing becau i colour in dis Marcus Garvey country proud an strong

an wrong – yu sun gone out & still you colour wrong.

inn got no i say song

i wonda whe Port Royal is. when de eart goin again goin crack

my daughta Ingriid walk beside me hurt

an strong an dress in black

her face inside she face int mekkin sport

on the tenth night after a long long distance silence

i born into this world w/ nothing but my breath & my bare back an hornets

in my chess

now i will haffe doubt if god is good & black & honesty

wha good good do fe me?

whe god dat cricket midnight criminal when Mark of god get call like dat & kill

Mark cyaan dead so if good. if god

my breath give birt to good like god

my sun dis gold is all my riches that cannot be replace

an suddenly me cannot fine him in dis place before dis good god face to face

wha good fe god. no god. what good. wha god. no god

if good Mark have no face to face dis god inside dis good god place

on the eleventh day after he dead

[Silence]

on the twelfth day

after yr debt – o pickney – it is as if me cyaaan wake up

Time has been drain from all my clocks. the sky is overcyas & lock

altho it isn’t rainin yet

[Silence]

this night we hold our wake. watch w/ the spirit of my sum before his daily funeral

. people cook food bring bread & drink & there’s some singing

of the old traditions by the older folks & country citizens

but they soon fall to arguing and they soon fall down to quarrellin

about the words the phrases time & tempo of these sookey tunes

it seem they isolated in the old traditions in these coffee hills

[poem continues in Born to Slow Horses]

Please note: This poem appears with different fonts in the original collection.

Copyright © 2005 by Kamau Brathwaite, Born to Slow Horses, Wesleyan University Press