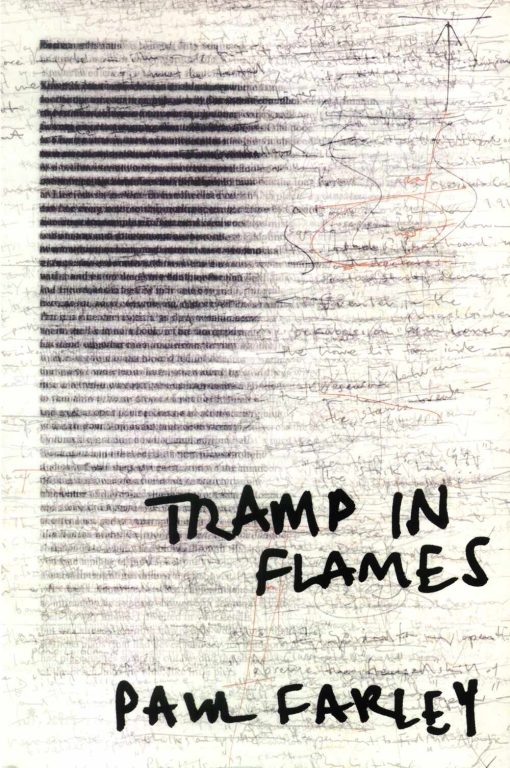

Paul Farley won the Arvon Poetry Competition Competition in 1996. His first poetry collection, The Boy From the Chemist is Here to See You (1998), won the Forward Poetry Prize for Best First Collection and a Somerset Maugham Award, and was shortlisted for the Whitbread Poetry Award. He was named Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year (1999). He received an Arts Council Writers’ Award in 2000. The Ice Age (2002) won the 2003 Whitbread Poetry Award and was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize. In addition to being shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize, Paul Farley’s Tramp in Flames won the 2006 Forward Prize for Best Individual Poem for ‘Liverpool Disappears for a Billionth of a Second’. Paul Farley currently lectures in Creative Writing at the University of Lancaster. He lives in England.

Judges’ Citation

Paul Farley is a poet of wit, sensuality and warmth.

Paul Farley is a poet of wit, sensuality and warmth. His work engages with the commonplace and the overlooked, the absurd and the catastrophic, the scientific and the mythic, in ways that make us stop and think again about what it is to be living in this particular world, at this particular moment in our history. Though he wears his learning lightly, Farley draws upon philosophy and natural science, as well as a deep, occasionally elegiac affection for the streets and fields and hillsides of the places he has called home, to create a poetry of exceptional formal skill. What makes his work so remarkable is that, whatever his subject matter, from the city of Liverpool to an old Ovaltine tin, everything is transformed by his imagination and his formal gifts, making us think again about what we know, and what we think we know. That said, however, what comes across most vividly here is the sheer music of the writing: every line sings off the page, and there can be few poets whose work is so memorable. If the best poetry aspires to the condition of music, as Mallarmé suggests, then this is poetry of the highest order: melodic, humane and intellectually engaging, Tramp in Flames renews our contract with the given world, yet challenges us to think again about what we see, and what we take for granted.

Selected poems

by Paul Farley

Shorter than the blink inside a blink

the National Grid will sometimes make, when you’ll

turn to a room and say: Was that just me?

People sitting down for dinner don’t feel

their chairs taken away/put back again

much faster than that trick with tablecloths.

A train entering the Olive Mount cutting

shudders, but not a single passenger

complains when it pulls in almost on time.

The birds feel it, though, and if you see

starlings in shoal, seagulls abandoning

cathedral ledges, or a mob of pigeons

lifting from a square as at gunfire,

be warned, it may be happening, but then

those sensitive to bat-squeak in the backs

of necks, who claim to hear the distant roar

of comets on the turn – these may well smile

at a world restored, in one piece; though each place

where mineral Liverpool goes wouldn’t believe

what hit it: all that sandstone out to sea

or meshed into the quarters of Cologne.

I’ve felt it a few times when I’ve gone home,

if anything, more often now I’m old,

and the gaps between get shorter all the time.

Copyright © Paul Farley 2006

Liverpool Disappears for a Billionth of a Second

My clock has gone although the sun has yet to take the sky.

I thought I was the first to see the snow, but his old eyes

have marked it all before I catch him in his column of light:

a rolled up metal shutter-blind, a paper bale held tight

between his knees so he can bring his blade up through the twine,

and through his little sacrifice he frees the day’s headlines:

its strikes and wars, the weather’s big seize up, runs on the pound.

One final star still burns above my head without a sound

as I set off. The dark country I grew up in has gone.

Ten thousand unseen dawns will settle softly on this one.

But with the streets all hushed I take the papers on my round

into the gathering blue, wearing my luminous armband.

Copyright © Paul Farley 2006

The Newsagent

The scarecrow wears a wire in the top field.

At sundown, the audiophilic farmer

who bugged his pasture unpicks the concealed

mics from his lapels. He’s by the fire

later, listening back to the great day,

though to the untrained ear there’s nothing much

doing: a booming breeze, a wasp or bee

trying its empty button-hole, a stitch

of wrensong now and then. But he listens late

and nods off to the creak of the spinal pole

and the rumble of his tractor pulling beets

in the bottom field, which cuts out. In a while

somebody will approach over ploughed earth

in caked Frankenstein boots. There’ll be a noise

of tearing, and he’ll flap awake by the hearth

grown cold, waking the house with broken cries.

Copyright © Paul Farley 2006