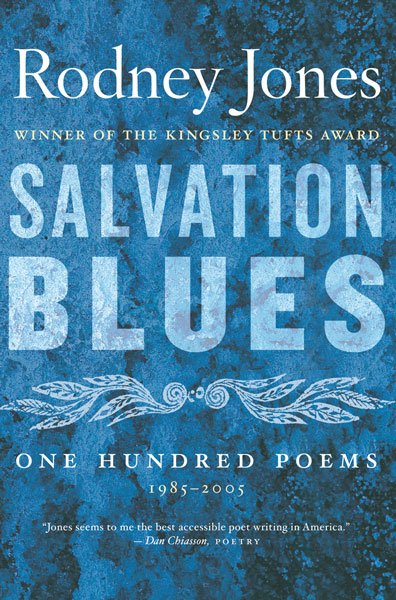

Salvation Blues is Rodney Jones’ eighth book of poetry. Previous collections include Kingdom of the Instant: Poems (2004); Elegy for the Southern Drawl (1999); Things That Happen Once (1996); Apocalyptic Narrative (1993); Transparent Gestures (1989); The Unborn (1985); and The Story They Told Us of Light (1980). He was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the winner of the 1989 National Book Critics Circle Award. His other honours include a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Peter I.B. Lavan Award from the Academy of American Poets, the Jean Stein Award from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, a Southeast Booksellers Association Award, and a Harper Lee Award. Rodney Jones is a professor of English at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale.

Judges’ Citation

His poems are angry, bawdy, funny, wise and deeply moving. They sing to remind us of our humanity and to heal the language of its long service as a mere tool.

There are not many poets who get as much of American life in their poems as Rodney Jones. His Salvation Blues, a book made up of one hundred poems taken from six previous collections published over the last twenty years, brings to mind Whitman. Jones asks in a poem, what happened to all the people the older poet cheered westward across the continent? They are all here in his poems, making ends meet, working as farmers, shipping clerks, waitresses, car mechanics, butchers, strippers and teachers, while trying their best to believe in the American dream and a religion whose preachers tend to be actors and salesmen whose pulpit is television. Jones is a marvelous story teller and a contemplative man with an interest in both character and the way the world works. ‘Most of us are compositions that begin in error,’ he says. He never forgets that. His poems are angry, bawdy, funny, wise and deeply moving. They sing to remind us of our humanity and to heal the language of its long service as a mere tool.

Selected poems

by Rodney Jones

I find joy in the cemetery trees.

Their roots are in our hearts.

In their leaves the soul

of another century is in ascension.

I hear the rustling of their branches

and watch the exhausted laborers

from the Burgreen Construction Company

sit down in the shade,

unwrapping their ham and salami

and popping open their thermoses.

Apparently, they too are enamored

of the hickory and willow

at the edge of our cemetery.

They are stretching twine, building a wall

as though this could be contained.

Probably they do not think

of our grandmothers who are pierced,

and probably do not want

to hear about Thomas Hardy,

who, if I remember, has been dead

longer than they have been alive,

And who gave to the leaves of one yew

the names of his own dead. Anyway

the only spirits I can call in this place

are the stench of a possum

suppurating in secret weeds

and the flies, who are marvelous

because their appetite is our revulsion.

Let the laborers go on. Right now

I wish I could admire the trees simply

for their architecture. All winter

the dying have set their tables

and now they are almost as black

as the profound waters off Guam.

A few minutes ago, when they started

in a slight breeze off the lake,

the many and patient sails,

I could see in those motions

a little of the world that owns me —

and that I cannot understand —

rise in its indifferent passion.

Copyright © 2006 by Rodney Jones

I Find Joy In the Cemetery Trees

The front seats filled last. Laggards, buffoons,

and kiss-ups falling in beside local politicos,

the about to be honored, and the hard of hearing.

No help from the middle, blenders and criminals.

And the back rows: restless, intelligent, unable to commit.

My place was always left-center, a little to the rear.

The shy sat with me, fearful of discovery.

Behind me the dead man’s illegitimate children

and the bride’s and groom’s former lovers.

There, when lights were lowered, hands

plunged under skirts or deftly unzipped flies,

and, lights up again, rose and pattered in applause.

Ahead, the bored practiced impeccable signatures.

But was it a movie or a singing? I remember

the whole crowd uplifted, but not the event

or the word that brought us together as one—

One, I say now, when I had felt myself many,

speaking and listening: that was the contradiction.

Copyright © 2006 by Rodney Jones

Sitting with Others

Willie Cooper, what are you doing here, this early in your death?

To show us what we are, who live by twisting words—

Heaven is finished. A poet is anachronistic as a blacksmith.

You planted a long row and followed it. Signed your name X

for seventy years.

Poverty is not hell. Fingers cracked by frost

And lacerated by Johnson grass are not hell.

Hell is what others think we are.

You told me once, “Never worry.”

Your share of worry was as small as your share of the profits,

Mornings-after of lightning and radiator shine,

The beater Dodge you bought in late October—

By February, its engine would hang from a rafter like a ham.

You had a free place to stay, a wife

Who bore you fourteen children. Nine live still.

You live in the stripped skeleton of a shovelbill cat.

Up here in the unforgivable amnesia of libraries,

Where many poems lie dying of first-person omniscience,

The footnotes are doing their effete dance, as always.

But only one of your grandsons will sleep tonight in Kilby Prison.

The hackberry in the sand field will be there long objectifying.

Once I was embarrassed to have to read for you

A letter from Shields, your brother in Detroit,

A hick-grammared, epic lie of northern women and money.

All I want is to get one grain of the dust to remember.

I think it was your advice I followed across the oceans.

What can I do for you now?

Copyright © 2006 by Rodney Jones

The Work of Poets

All the preachers claiming it was Satan–

And now the first sets seem more venerable

Than Abraham or Williamsburg

Or the avant-garde, but then nothing,

Not even the bomb, had ever looked so new,

So it seemed almost heretical watching it

When we visited relatives in the city,

Secretly delighting, but saying later,

After church, probably it would not last,

It would destroy things: the standards,

And the sacredness of words in books.

So it was well into the age of color,

And Korea and Little Rock long past,

Before anyone got one, and then some

Of them in the next valley had one,

And you would know them by their lights

Burning late at night, and the recentness

And distance of events entering their talk,

But not one in our valley; for a long time

No one had one, so when the first one

Arrived in the van from the furniture store

And the men had set the box on the lawn,

At first we stood back from it, circling it

As they raised the antenna and staked in

The guy wires before taking it in the door,

And I seem to recall a kind of blue light

Flickering from inside and then a woman

Calling out that they had got it tuned in–

A little fuzzy, a ghost picture, but something

That would stay with us, the way we hurried

Down the dirt road, the stars, the silence,

Then everyone disappearing into the houses.

Copyright © 2006 by Rodney Jones