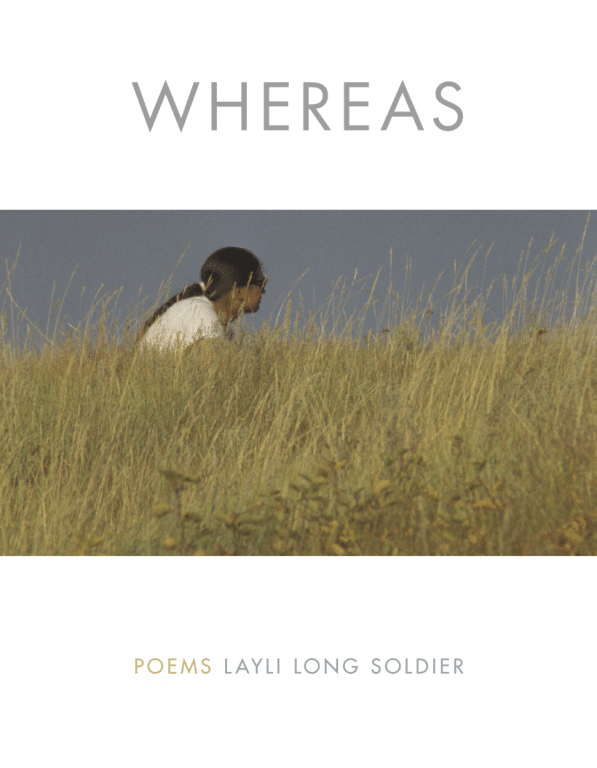

Layli Long Soldier earned a BFA from the Institute of American Indian Arts and an MFA with honours from Bard College. She is the author of the chapbook Chromosomory (2010) and the full-length collection Whereas (2017), which was a finalist for the National Book Awards. She has been a contributing editor to Drunken Boat and is poetry editor at Kore Press; in 2012, her participatory installation, Whereas We Respond, was featured on the Pine Ridge Reservation. In 2015, Long Soldier was awarded a National Artist Fellowship from the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation and a Lannan Literary Fellowship for Poetry. A citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation, Long Soldier lives in Tsaile, Arizona, in the Navajo Nation, with her husband and daughter. She is an adjunct faculty member at Diné College.

Judges’ Citation

Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas repurposes congressional doublespeak in order to lay bare the murderous hypocrisy lurking behind the official language of the state.

Selected poems

by Layli Long Soldier

Keep in mind, I am not a historian.

So I will recount facts as best as I can, given limited resources and understanding.

Before Minnesota was a state, the Minnesota region, generally speaking, was the traditional homeland for Dakota, Anishnaabeg and Ho-Chunk people.

During the 1800s, when the US expanded territory, they “purchased” land from the Dakota people as well as the other tribes.

But another way to understand that sort of “purchase” is: Dakota leaders ceded land to the US government in exchange for money and goods, but most importantly, the safety of their people.

Some say that Dakota leaders did not understand the terms they were entering, or they never would have agreed.

Even others call the entire negotiation, “trickery.”

But to make whatever-it-was official and binding, the US government drew up an initial treaty.

This treaty was later replaced by another (more convenient) treaty, and then another.

I’ve had difficulty unraveling the terms of these treaties, given the legal speak and congressional language.

As treaties were abrogated (broken) and new treaties were drafted, one after another, the new treaties often referenced old defunct treaties and it is a muddy, switchback trail to follow.

Although I often feel lost on this trail, I know I am not alone.

However, as best as I can put the facts together, in 1851, Dakota territory was contained to a twelve-mile by one-hundred-fifty-mile long strip along the Minnesota River.

But just seven years later, in 1858, the northern portion was ceded (taken) and the southern portion was (conveniently) allotted, which reduced Dakota land to a stark ten-mile tract.

These amended and broken treaties are often referred to as the Minnesota Treaties.

The word Minnesota comes from mni which means water; sota which means turbid.

Synonyms for turbid include muddy, unclear, cloudy, confused and smoky.

Everything is in the language we use.

For example, a treaty is, essentially, a contract between two sovereign nations.

The US treaties with the Dakota Nation were legal contracts that promised money.

It could be said, this money was payment for the land the Dakota ceded; for living within assigned boundaries (a reservation); and for relinquishing rights to their vast hunting territory which, in turn, made Dakota people dependent on other means to survive: money.

The previous sentence is circular, which is akin to so many aspects of history.

As you may have guessed by now, the money promised in the turbid treaties did not make it into the hands of Dakota people.

In addition, local government traders would not offer credit to “Indians” to purchase food or goods.

Without money, store credit or rights to hunt beyond their ten-mile tract of land, Dakota people began to starve.

The Dakota people were starving.

The Dakota people starved.

In the preceding sentence, the word “starved” does not need italics for emphasis.

One should read, “The Dakota people starved,” as a straightforward and plainly stated fact.

As a result—and without other options but to continue to starve—Dakota people retaliated.

Dakota warriors organized, struck out and killed settlers and traders.

This revolt is called the Sioux Uprising.

Eventually, the US Cavalry came to Mnisota to confront the Uprising.

More than one thousand Dakota people were sent to prison.

As already mentioned, thirty-eight Dakota men were subsequently hanged.

After the hanging, those one thousand Dakota prisoners were released.

However, as further consequence, what remained of Dakota territory in Mnisota was dissolved (stolen).

The Dakota people had no land to return to.

This means they were exiled.

Homeless, the Dakota people of Mnisota were relocated (forced) onto reservations in South Dakota and Nebraska.

Now, every year, a group called the The Dakota 38 + 2 Riders conduct a memorial horse ride from Lower Brule, South Dakota to Mankato, Mnisota.

The Memorial Riders travel 325 miles on horseback for eighteen days, sometimes through sub-zero blizzards.

They conclude their journey on December 26th, the day of the hanging.

Memorials help focus our memory on particular people or events.

Often, memorials come in the forms of plaques, statues or gravestones.

The memorial for the Dakota 38 is not an object inscribed with words, but an act.

Yet, I started this piece because I was interested in writing about grasses.

So, there is one other event to include, although it’s not in chronological order and we must backtrack a little.

When the Dakota people were starving, as you may remember, government traders would not extend store credit to “Indians.”

One trader named Andrew Myrick is famous for his refusal to provide credit to Dakotas by saying, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.”

There are variations of Myrick’s words, but they are all something to that effect.

When settlers and traders were killed during the Sioux Uprising, one of the first to be executed by the Dakota was Andrew Myrick.

When Myrick’s body was found,

his mouth was stuffed with grass.

I am inclined to call this act by the Dakota warriors a poem.

There’s irony in their poem.

There was no text.

“Real” poems do not “really” require words.

I have italicized the previous sentence to indicate inner dialogue; a revealing moment.

But, on second thought, the particular words “Let them eat grass,” click the gears of the poem into place.

So, we could also say, language and word choice are crucial to the poem’s work.

Things are circling back again.

Sometimes, when in a circle, if I wish to exit, I must leap.

And let the body

swing.

From the platform.

Out

to the grasses.

From Whereas by Layli Long Soldier

Copyright © 2017 by Layli Long Soldier

38

Keep in mind, I am not a historian.

So I will recount facts as best as I can, given limited resources and understanding.

Before Minnesota was a state, the Minnesota region, generally speaking, was the traditional homeland for Dakota, Anishnaabeg and Ho-Chunk people.

During the 1800s, when the US expanded territory, they “purchased” land from the Dakota people as well as the other tribes.

But another way to understand that sort of “purchase” is: Dakota leaders ceded land to the US government in exchange for money and goods, but most importantly, the safety of their people.

Some say that Dakota leaders did not understand the terms they were entering, or they never would have agreed.

Even others call the entire negotiation, “trickery.”

But to make whatever-it-was official and binding, the US government drew up an initial treaty.

This treaty was later replaced by another (more convenient) treaty, and then another.

I’ve had difficulty unraveling the terms of these treaties, given the legal speak and congressional language.

As treaties were abrogated (broken) and new treaties were drafted, one after another, the new treaties often referenced old defunct treaties and it is a muddy, switchback trail to follow.

Although I often feel lost on this trail, I know I am not alone.

However, as best as I can put the facts together, in 1851, Dakota territory was contained to a twelve-mile by one-hundred-fifty-mile long strip along the Minnesota River.

But just seven years later, in 1858, the northern portion was ceded (taken) and the southern portion was (conveniently) allotted, which reduced Dakota land to a stark ten-mile tract.

These amended and broken treaties are often referred to as the Minnesota Treaties.

The word Minnesota comes from mni which means water; sota which means turbid.

Synonyms for turbid include muddy, unclear, cloudy, confused and smoky.

Everything is in the language we use.

For example, a treaty is, essentially, a contract between two sovereign nations.

The US treaties with the Dakota Nation were legal contracts that promised money.

It could be said, this money was payment for the land the Dakota ceded; for living within assigned boundaries (a reservation); and for relinquishing rights to their vast hunting territory which, in turn, made Dakota people dependent on other means to survive: money.

The previous sentence is circular, which is akin to so many aspects of history.

As you may have guessed by now, the money promised in the turbid treaties did not make it into the hands of Dakota people.

In addition, local government traders would not offer credit to “Indians” to purchase food or goods.

Without money, store credit or rights to hunt beyond their ten-mile tract of land, Dakota people began to starve.

The Dakota people were starving.

The Dakota people starved.

In the preceding sentence, the word “starved” does not need italics for emphasis.

One should read, “The Dakota people starved,” as a straightforward and plainly stated fact.

As a result—and without other options but to continue to starve—Dakota people retaliated.

Dakota warriors organized, struck out and killed settlers and traders.

This revolt is called the Sioux Uprising.

Eventually, the US Cavalry came to Mnisota to confront the Uprising.

More than one thousand Dakota people were sent to prison.

As already mentioned, thirty-eight Dakota men were subsequently hanged.

After the hanging, those one thousand Dakota prisoners were released.

However, as further consequence, what remained of Dakota territory in Mnisota was dissolved (stolen).

The Dakota people had no land to return to.

This means they were exiled.

Homeless, the Dakota people of Mnisota were relocated (forced) onto reservations in South Dakota and Nebraska.

Now, every year, a group called the The Dakota 38 + 2 Riders conduct a memorial horse ride from Lower Brule, South Dakota to Mankato, Mnisota.

The Memorial Riders travel 325 miles on horseback for eighteen days, sometimes through sub-zero blizzards.

They conclude their journey on December 26th, the day of the hanging.

Memorials help focus our memory on particular people or events.

Often, memorials come in the forms of plaques, statues or gravestones.

The memorial for the Dakota 38 is not an object inscribed with words, but an act.

Yet, I started this piece because I was interested in writing about grasses.

So, there is one other event to include, although it’s not in chronological order and we must backtrack a little.

When the Dakota people were starving, as you may remember, government traders would not extend store credit to “Indians.”

One trader named Andrew Myrick is famous for his refusal to provide credit to Dakotas by saying, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.”

There are variations of Myrick’s words, but they are all something to that effect.

When settlers and traders were killed during the Sioux Uprising, one of the first to be executed by the Dakota was Andrew Myrick.

When Myrick’s body was found,

his mouth was stuffed with grass.

I am inclined to call this act by the Dakota warriors a poem.

There’s irony in their poem.

There was no text.

“Real” poems do not “really” require words.

I have italicized the previous sentence to indicate inner dialogue; a revealing moment.

But, on second thought, the particular words “Let them eat grass,” click the gears of the poem into place.

So, we could also say, language and word choice are crucial to the poem’s work.

Things are circling back again.

Sometimes, when in a circle, if I wish to exit, I must leap.

And let the body

swing.

From the platform.

Out

to the grasses.

Copyright © 2017 by Layli Long Soldier

from 38

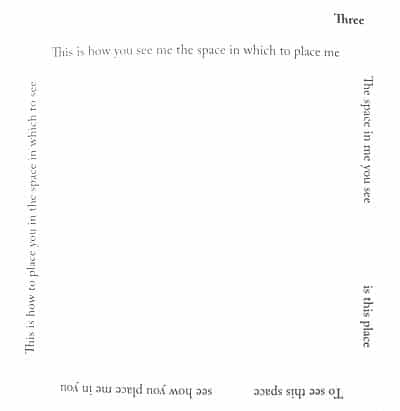

Three

This is how you see me the space in which to place me

The space in me you see is this place

To see this space see how you place me in you

This is how to place you in the space in which to see

Copyright © 2017 by Layli Long Soldier

from He Sápa

However a light may come

through vaporative

glass pane or dry dermis

of hand winter bent

I follow that light

capacity that I have

cup-sized capture

snap-like seizure I

remember small

is less to forget

less to carry

tiny gears mini-

armature I gun

the spark light

I blink eye blink

at me to look

at me in

light eye

look twice

and I eye

alight

again.

Copyright © 2017 by Layli Long Soldier

from Vaporative

But

is the small way to begin.

But I could not.

As I am limited to few

words at command, such as wanblí. This

was how I wanted to begin, with the little

I know.

But could not.

Because this wanblí, this eagle

of my imagining is not spotted, bald,

nor even a nest-eagle. It is gold,

though by definition, not ever the great Golden Eagle.

Much as the gold, by no mistake, is not ground-gold,

man-gold or nugget. But here, it is

the gold of light and wing together.

Wings that do not close, but in expanse

angle up so slightly; plunge with muscle

and stout head somewhere between

my uncle, son, father, brother.

But I failed to begin there, with this

expanse. Much as I failed to start

with the great point in question.

There in muscle in high inner flight always

in the plunge we fear for the falling, we buckle to wonder:

What man is expendable?

Copyright © 2017 by Layli Long Soldier