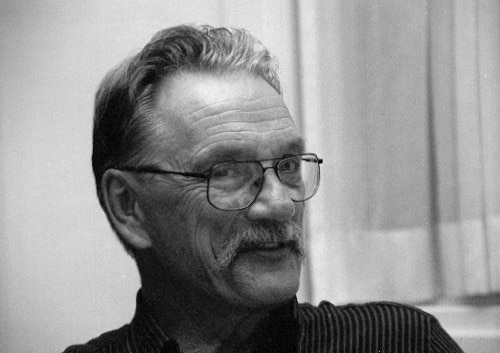

Born in Penticton, British Columbia in 1935, George Bowering has had a multi-faceted career as poet, novelist, essayist, critic, teacher, historian, and editor. After serving as an aerial photographer in the RCAF, he attended the University of British Columbia where he earned a BA in History and an MA in English, and took part in establishing the post modernist, avant-garde movement in B.C. by co-founding and co-editing TISH. Bowering taught at the University of Calgary, the University of Western Ontario, and Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. He is one of Canada’s most prolific writers of poetry, short stories and novels with more than 100 titles to his credit.

In recognition of his extraordinary accomplishments, Bowering was named Canada’s First Poet Laureate in 2002. The much-lauded Officer of the Order of Canada has won the Governor General’s Award for Poetry in 1969, the Governor General’s Award for Fiction in 1980, the bP Nichol Chapbook Award for Poetry in both 1991 and 1992, the Canadian Author’s Association Award for Poetry in 1993 and was awarded an Honorary Degree (D. Litt.) from the University of British Columbia in 1994. His collections of poems include Sticks and Stones (1963), Rocky Mountain Foot (1969), The Gangs of Kosmos (1969), Touch: Selected Poems (1960-1969), In the Flesh (1974), Delayed Mercy and Other Poems (1986), Sticks and Stones (1989), Urban Snow (1992), George Bowering Selected Poems 1961-1992 (1993), Vermeer’s Light, Poems 1996-2006 (2006), and more. He lives in Vancouver, B.C.

Judges’ Citation

In George Bowering’s flight changes, lyric takes to the air – with spareness, resiliency and irrepressible humour.

In George Bowering’s flight changes, lyric takes to the air – with spareness, resiliency and irrepressible humour. This collection from 40 years of playful seriousness extends lyric form in a marvellous variety of ways, condensing a remarkable agility, an exuberance in the singular voice and in feelings’ construct and presentation. It is irreverent, yet leaves us in the hush of reverence. Bowering’s voice is instantly recognisable throughout, in all its variants, its pulling of high into ‘low’ culture, its borrowings from older poetries we all know. Bowering is the poet of delight in earthly matters, of bemusement at the self. His lyrics turn out the streetlights (who needs them!) and light up the stars. And his lines try to understand what it is to exist, in the face of fears we all have, ‘fears that I may cease to be.

Selected poems

by George Bowering

This sudden snow:

immediately

the prairie is!

Those houses are:

dark

under roofs of snow –

That hill up to the cloud is:

markt

by snow creeks down to town –

This footpath is:

a bare line

across white field –

This woman appears

thru drift of snow:

a red coat.

Copyright © 2004 by George Bowering, Changing on the Fly, Raincoast Books

A Sudden Measure

I walkt to the back of the house in the

yard near the garage & saw him in a

white shirt playing ping pong with a patient

or friend or someone else who lived in the

house & there he was.

I sat at the table where we were reading

aloud together & heard him from behind where

he was crying aloud & wearing his pink

leather number on the west coast & I

must tell you he is a star.

Maybe Holofernes.

He tried to grow a mustache & took his

vacation in a classy hotel in bermuda where

he sat & drank bourbon with ice, a poet

taking his own kind of holiday, hooray.

Judy lookt as if she wanted to be him

or be with him or kill him.

I think that all the time he was listening

to the ice in the glass his ear was thinking

ping

pong

ping

pong

pingngngngng

One time he placed a bottle of Pinch on the

coat hook on the back of the door in our

clothes closet & we opened & closed the door

for two months before we found the bottle

of Pinch & it should have fallen off many

times so we drank it & later I bought him

a bottle of Pinch in August because the night

before we had been drinking bourbon on his

credit card in the bar where he goes to

drink his own way, the poet.

There he was, on the tape, all over the

country, making personal appearances, Captain

Poetry, listening to the voice of the four

horsemen in the children’s fiery

chamber of verse.

Copyright © 2004 by George Bowering, Changing on the Fly, Raincoast Books

bpNichol

I’m going to write a poem about life & death, I said, but mostly about death. But you are always doing that, said D, your last poem was about death. The poem before that one was about death. In fact if you looked at all your writing, especially the poems, you would find pretty near nothing but death. A lot of the time you seem to be laughing about it, but that doesnt fool anyone.

Yes, but this time I am going to make it a real poem about life but mainly death, I’ll grant you that. None of that lacy Rilke death, none of that ho ho Vonnegut death. I mean real death or I should say real thinking about death. For instance? asked D. Well, for instance, take the way you feel like how awful it would be when you cant put an arm around a perfect waist, & there is that swelling out of hip upon which it is natural to rest an arm. How wonderful, and how terrible not to be able to look forward to that ever again.

You see? said D, you announce that you are going to say something straight about death, and there you are talking about life, as far as I can see. That’s just my point, I said. Death will be horrible because it won’t have anything of life in it, no matter how many fancypants graduate students have told me that you can’t really submerge yourself in life unless you are fully conscious of your death. They have all been reading Albert Camus lately, & they are so much wiser than I am.

I suppose you are using all of the things I have been saying as part of your poem, said D. Of course, I said. You are to this poem as a swelling out of lovely hip is to an arm that has snaked around a dear waist.

Just then I realized that I had made D up in my imagination, & now there was no D at all, & I had to forget about writing another poem about life & death, but especially about death, especially about death from a straight point of view, because M came into the room while I was typing & had a persistent gripe about C, & no matter how interrupted I managed to make myself look on the chair in front of the keyboard, M just kept on & on till the poem had followed D to some place we will never find the way to.

Copyright © 2004 by George Bowering, Changing on the Fly, Raincoast Books