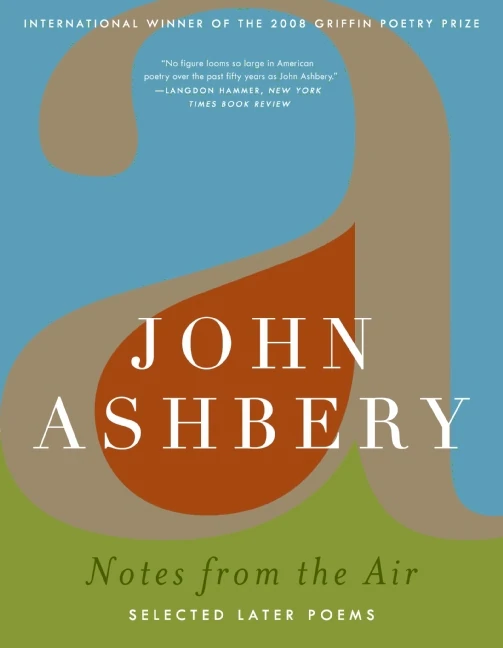

John Ashbery was born in Rochester, New York in 1927. Best known as a poet, he is the author of over 20 books of poetry including Some Trees, which was selected by W.H. Auden for the Yale Younger Poets Series and Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, which received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, the National Book Critics Circle Award and the National Book Award. He has served as executive editor of ARTnews magazine and as the art critic for New York and Newsweek magazines. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Ashbery served as Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets from 1988 to 1999. He has received two Guggenheim Fellowships and was a MacArthur Fellow from 1985 to 1990. His work has been translated into more than 20 languages. John Ashbery lives in New York.

Judges’ Citation

The pleasure of reading John Ashbery’s poetry defies explanation.

The pleasure of reading John Ashbery’s poetry defies explanation. The YOU the author makes reference to is ME, the transcription being rendered, paradoxically, by a poet who eschews autobiography; thus the I as well as the YOU names the reader. Ashbery’s is one of the best and most intense poetry productions of the twentieth century. Its famous difficulty does not repel: it invites. It offers a ‘site of survival,’ a real mirror for human beings today, providing a place of honour and dignity for the very personal and secret hidden in everyone. His poems reach the private part of each individual. No wonder he has declared in interviews that he’s ‘like everybody else’ – the body breathing inside the poem is as much himself as ourselves. But the person who knows how to observe and therefore how to be unique is John Ashbery, ungraspable, inexplicable and as mysterious as the Delphic oracle. In Notes from the Air, Ashbery has taken the opportunity provided a long-living poet not to collect but to select what in his opinion constitutes the best part of his later production. These ‘notes’ proceeding from the air or written by it honour the defining economy of poetry, unique lexical territory where one cannot go against the plurality of meaning embodied in words. He grants unity to this volume by sequencing poems deftly linked, forged with the delicateness of time, its overwhelming theme. The vigilant eye cast on this selection is omnipresent, and does not let a single detail go loose. With this personal organization of the most meaningful part of his work, Ashbery offers a new way of reading it, testing language by virtue of the American tongue, making it a true ‘remnant of energy’ for which only the poet can take responsibility.

Selected poems

by John Ashbery

It was a night for listening to Corelli, Geminiani

Or Manfredini. The tables had been set with beautiful white cloths

And bouquets of flowers. Outside the big glass windows

The rain drilled mercilessly into the rock garden, which made light

Of the whole thing. Both business and entertainment waited

With parted lips, because so much new way of being

With one’s emotion and keeping track of it at the same time

Had been silently expressed. Even the waiters were happy.

It was an example of how much one can grow lustily

Without fracturing the shell of coziness that surrounds us,

And all things as well. “We spend so much time

Trying to convince ourselves we’re happy that we don’t recognize

The real thing when it comes along,” the Disney official said.

He’s got a point, you must admit. If we followed nature

More closely we’d realize that, I mean really getting your face pressed

Into the muck and indecision of it. Then it’s as if

We grew out of our happiness, not the other way round, as is

Commonly supposed. We’re the characters in its novel,

And anybody who doubts that need only look out of the window

Past his or her own reflection, to the bright, patterned,

Timeless unofficial truth hanging around out there,

Waiting for the signal to be galvanized into a crowd scene,

Joyful or threatening, it doesn’t matter, so long as we know

It’s inside, here with us.

But people do change in life,

As well as in fiction. And what happens then? Is it because we think nobody’s

Listening that one day it comes, the urge to delete yourself,

“Take yourself out,” as they say? As though this could matter

Even to the concerned ones who crowd around,

Expressions of lightness and peace on their faces,

In which you play no part perhaps, but even so

Their happiness is for you, it’s your birthday, and even

When the balloons and fudge get tangled with extraneous

Good wishes from everywhere, it is, I believe, made to order

For your questioning stance and that impression

Left on the inside of your pleasure by some bivalve

With which you have been identified. Sure,

Nothing is ever perfect enough, but that’s part of how it fits

The mixed bag

Of leftover character traits that used to be part of you

Before the change was performed

And of all those acquaintances bursting with vigor and

Humor, as though they wanted to call you down

Into closeness, not for being close, or snug, or whatever,

But because they believe you were made to fit this unique

And valuable situation whose lid is rising, totally

Into the morning-glory-colored future. Remember, don’t throw away

The quadrant of unused situations just because they’re here:

They may not always be, and you haven’t finished looking

Through them all yet. So much that happens happens in small ways

That someone was going to get around to tabulate, and then never did,

Yet it all bespeaks freshness, clarity and an even motor drive

To coax us out of sleep and start us wondering what the new round

Of impressions and salutations is going to leave in its wake

This time. And the form, the precepts, are yours to dispose of as you will,

As the ocean makes grasses, and in doing so refurbishes a lighthouse

On a distant hill, or else lets the whole picture slip into foam.

Copyright © 2007 by John Ashbery

Someone You Have Seen Before

As one turns to one in a dream

smiling like a bell that has just

stopped tolling, hold out a book

and speaks: “All the vulgarity

of time, from the Stone Age

to our present, with its noodle parlors

and token resistance, is as a life

to the life that is given you. Wear it,”

so must one descend from checkered heights

that are our friends, needlessly

rehearsing what we will say

as a common light bathes us,

a common fiction reverberates as we pass

to the celebration. Originally

we weren’t going to leave home. But made bold

somehow by the rain we put our best foot forward.

Now it’s years after that. It

isn’t possible to be young anymore.

Yet the tree treats me like a brute friend;

my own shoes have scarred the walk I’ve taken.

Copyright © 2007 by John Ashbery