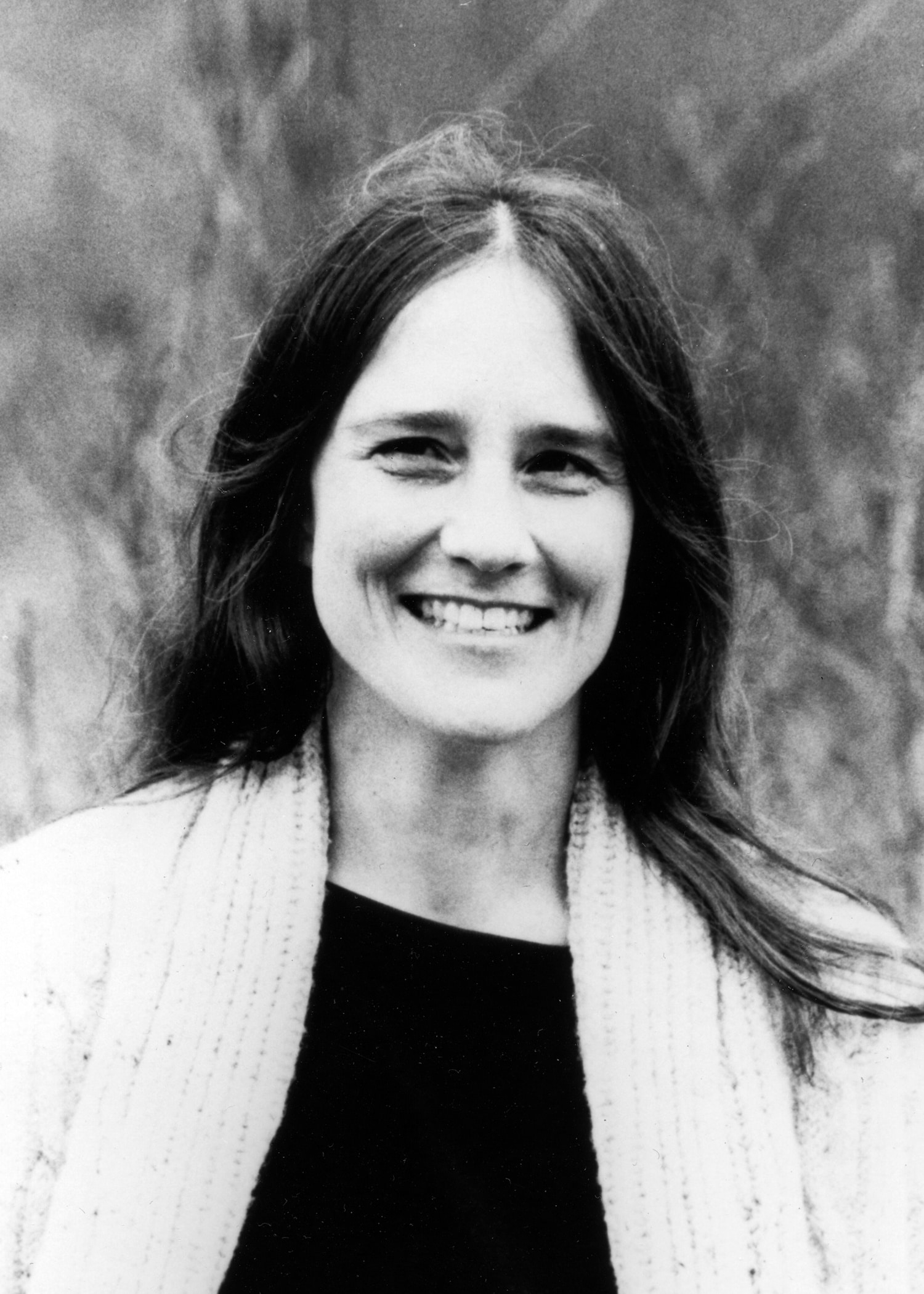

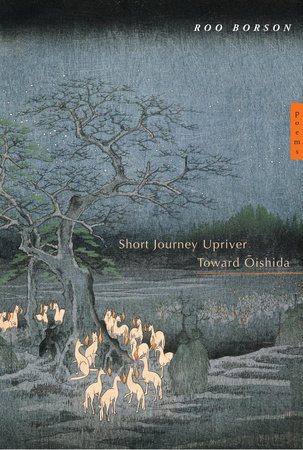

Born in California in 1952, Roo Borson has made her home in Canada since graduating with a Master of Fine Arts Degree from the University of British Columbia in 1977. Short Journey Upriver Toward Oishida, also winner of the Governor General’s and Pat Lowther Memorial Awards and shortlisted for the Trillium Book Prize, is her tenth book of poems, which include Water memory (1996) and Night Walk: Selected Poems (1994), a finalist for the Governor General’s Award. In addition to her prize winning essays, Borson’s poetry has won many awards including the CBC Prize for Poetry in 1982 and 1989, and has been a finalist for the National Magazine Awards in 1990 and 1993, the Governor General’s Award in 1984 as well as 1994, and in collaboration with Kim Maltman and Andy Patton as PAIN NOT BREAD, won the Long Poem Prize in the Malahat Review in 1993. Among her publications are: In the Smokey Light of the Fields (1980), Intent, Or, the Weight of the World (1989), Landfall (1977), Rain (1980), A Sad Device (1981), The Transparence of November; Snow (1985) and The Whole Night Coming Home (1984).

Borson has given readings across Canada, in the United States and in Australia, and has been published in a wide array of anthologies including The New Oxford Book of Canadian Verse, the Norton Introduction to Poetry, the Norton Introduction to Literature and The Morningside Papers. She has served as the writer in residence at both Concordia and the University of Western Ontario. Currently living in Toronto with poet and physicist Kim Maltman, along with Andy Patton and Maltman, Borson is a member of the Collaborative performance poetry ensemble PAIN NOT BREAD.

When the Griffin Trust took part in the Dublin Writers Festival in 2005, Roo Borson kept a blog of her observations and impressions – you can read it here.

Judges’ Citation

The book is a small perfection in its construction, moving deftly through seasons and forms: poetic prose for a garden of persimmons, haiku rising out of prose sequences for the autumn record, and the book’s fulcrum, the ‘Water Colour’ poems…

To lose ‘North’, in some idioms, is to lose all direction. In her journey, Borson finds North. This is the work of a poet writing at the height of her powers. It is a poetic journal of mortality, of the ‘why be born?’ and ‘do you still love poetry?’, of entering middle age, and of journeying through landscape, seasons, plants, pasts, to find it again. The book is a small perfection in its construction, moving deftly through seasons and forms: poetic prose for a garden of persimmons, haiku rising out of prose sequences for the autumn record, and the book’s fulcrum, the ‘Water Colour’ poems, not haiku but poems that bear haiku’s arrested feeling and succinct observation. As for Basho, Borson’s mentor and poetic ancestor, setting off toward North – lost, loss, losing – is to find the journey itself and one’s own corporeality, out of grief and into the light of words.

Selected poems

by Roo Borson

…

I followed the path into the woods, and just as my friend described, it led across the old railway bridge. The water beneath the bridge was wide and deep and not particularly clear. It seemed to swell as it flowed, as if pushing something unseen downriver. Indeed a large dredging barge was planed in the midst of the river, doing its unseen work. At one point along the right-hand side of the bridge was a bronze plaque, along with three poems and some plastic flowers tacked to the wooden railing. A boy had jumped to his death here some time ago it seemed, and the poems – one by his parents – were there not only to mark the loss, but also as a means of speaking with him directly. The poems, expressed in commonplaces, were not fine art, but they were communication. They were the sort of poems that say what they mean. Amazingly, almost superstitiously, people still fall back on writing poetry when they feel they have something truly important to communicate.

…

I understand the parents’ wish, despite everything, to speak to their son, though if it were up to me I’d take the poems and flowers down. Yet I too would like to place a poem on the bridge for those who’ve gone under, as well as those of us who’ve stayed above.

On the last night of the year

the swans set sail at evening.

Then among the boats and fireworks

we can see the black water,

the city in the river.

That’s where all our life is,

beyond the grief and failure,

the wake among the reeds.

Down there

down there

what is that place now

but a hill studded with lights

and a pine tree that doesn’t move with the wind?

Wherever there is summer,

wherever the crickets sing to it,

that place is.

But longing is a wind that blows through you,

and like the pine that is nowhere

you do not move.

Copyright © 2004 by Roo Borson

from A Bit of History

As for you, world –

you’ll have become small, and round, and lavender-coloured: ode

to the ewer, the comb, the water cooler.

And you? You lived in a place which was once a town,

you’ve seen it on maps before, others loaded ships

as in a dream: mood, appetite, memory, learning –

the demands seemed endless, all marsh-lights and loveliness,

the final estimates for the real world

or these propositions, for instance, which are sometimes true.

Indeed such unconscious concentration is possible,

in the neon light of early spring

and later, those evenings no longer fully spring

yet not quite summer either,

when the scent pulls back into the flower

and blackbirds bathe among violets,

half aspect, half unreal, in the slow rain of leaves.

Day after day, some days not returning,

and the boughs painted with light green lichen,

the detailed pink of the flowering apricot –

don’t go there unless to banish yourself,

because you are banished, beech,

oak, birch, and yew, among the hazel woods

of the elder world, where feathers flash

among the branches and hide in the darkening varnish

and history becomes the history of bad ideas,

a gloom of rotten nuts and nut-skins,

bitter paper. And tonight

the half-light in which paper glows –

walls, porticos, arches, places (who lived there?),

the print invisible, and the ocean sounding

all night long, clavicle to vena cava,

clavicle to vena cava,

it’s not a description.

Copyright © 2004 by Roo Borson