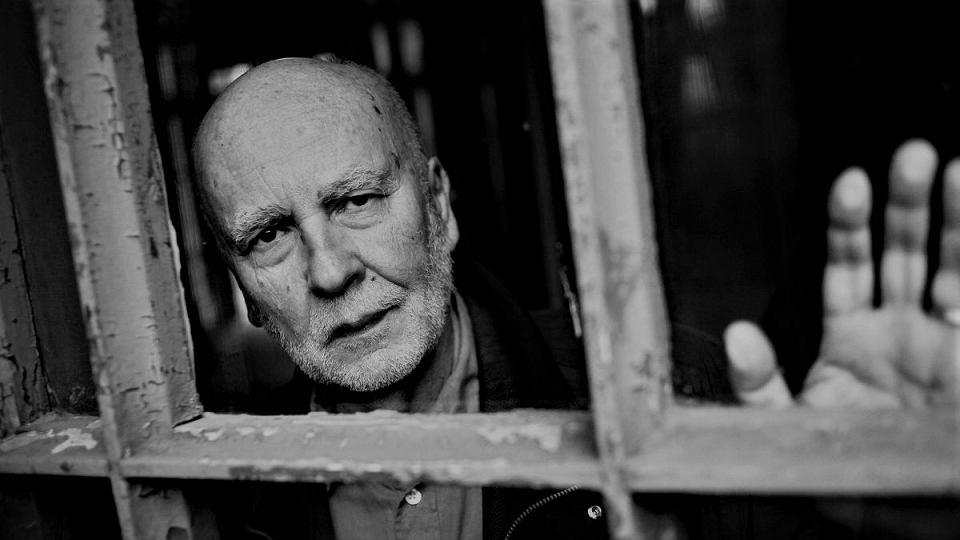

On June 1, Polish poet, novelist, translator and essayist Adam Zagajewski was presented with the Lifetime Recognition Award by trustee, Mark Doty.

Mark Doty pays tribute to Adam Zagajewski

Poets do not choose their relation to history. We are born when and where we are, some in the line of fire, some sheltered from difficult circumstances, most of us somewhere in between. Some are temperamentally at odds with their times, some prove just the right spirit to give voice to the complexities of the hour. Here in the still-new 21st century, readers who love poetry are fortunate nearly beyond measure, because we have a poet ideally suited to the tenor of these times, one whose work arises from the ash-heap of the 20tth century, and voices the real fears and tentative hopes of the 21st. I am profoundly honoured, on behalf of the Griffin trustees, to present the international award for lifetime achievement to one of the major poets of our era: Adam Zagajewski.

Adam Zagajewski was born in Lvov, Poland, in 1945. The deceptively neutral tone of that sentence disguises the fact that it is so freighted with the weight of history as to require us to immediately re-read it: Adam Zagajewski was born in Lvov, Poland, in 1945. The poet was born between occupations, in a city whose very name was recast again and again the language of whatever invader captured it. Lvov has in its time been Mongol, Galician, Austrian, Hungarian, Polish, Russian, Ukranian and German – a landscape of discontinuity, of radical uncertainty. This legacy may help to account for the quality Robert Pinsky identifies when he writes that Zagajewski’s poems are “about the presence of the past in ordinary life: history not as a chronicle of the dead … but as an immense, sometimes subtle force inhering in what people see and feel every day — and in the ways we see and feel.”

Those “ways we see and feel” are indeed shaped by history, but for a poet they are shaped by poetry as well. Although Zagajewski attended university in Krakow, his real education seems to have proceeded from the work of the poets he loved. The great Polish poets of the last century’s second half – Czeslaw Milosz, Zbigniew Herbert, Wislawa Syzmborska – belonged not just to Poland but to the world. They taught us how profoundly a poem that considered the past might take the temperature of the present, and how much a poem could say through indirection, and how deeply a poem contemplating the ordinary might penetrate into the depths of reality. Zagajewski began writing poems of protest against the repressions of the state – his work was, in fact, banned in Poland in 1975, and the poet lived in exile for 20 years, from 1982 until 2002. As his work has developed he has, like his great predecessors, moved in a contemplative direction, composing poems in which timeless experience intersects with the daily, historical world. “What really interests me,” he has written, “is the interweaving of the historical and the cosmic world, the motionless one, or rather (the one that moves) in a completely different motion. I will never understand how these two coexist.”

Zagajewski’s books of poetry in English include Unseen Hand: Poems (Farrar Straus, 2012), Eternal Enemies: Poems (2008); Without End: New and Selected Poems (2002); Mysticism for Beginners (1997); Tremor (1985); and Canvas (199). He is also the author of a memoir, Another Beauty (2000) and the prose collections, A Defense of Ardor (2005), Two Cities (1995) and Solitude and Solidarity (1990). He has received the Prix de la Liberte, the Kurt Tucholsky Priz, and fellowships from the Berliner Kunstlerprogramm, and the Guggenheim Foundation. He has taught at the University of Houston and the University of Chicago.

Zagajewski’s limpid, often spare poems are undeceived; they know the blade of the invader may appear at any time, or the muffling silence of repression. Yet he will not leave us without hope; his poems refuse the notion that we are powerless, even if all we can change are our own moments of perception. Here are just four lines of “Don’t Allow the Lucid Moment to Dissolve” as translated by Renata Gorczyinski:

Don’t allow the lucid moment to dissolve

Adam Zagajewski

Let the radiant thought last in stillness

though the page is almost filled and the flame flickers

We haven’t risen yet to the level of ourselves

That warm, clear voice feels trustworthy because it will not lie to us; it will not conceal the depredations of history, or the dangers of the present, yet calls us to our most human capacities. The possibilities that voice holds out to us mark what has become Zagajewski’s best-known poem in English, “Try to Praise the Mutilated World,” which was published in Clare Cavanagh’s translation on the back cover of The New Yorker just after September 11, 2001. It was written some time before, and when the world was torn again before the poem was published, its brave injunction remained just as necessary. Our capacity for praise may feel itself feel mutilated, it will be at times terribly difficult to find in ourselves the strength to praise, but Zagajewski’s essential poem reminds us that it is the human necessity to try. For what do we have, without praise, besides irony or bitterness? These poems make the work of affirmation more available to us; they remind us — gently, sometimes sardonically, but always with great compassion for what is mutilated in us — that the lucid moment is still possible.

Zagajewski’s limpid, often spare poems are undeceived; they know the blade of the invader may appear at any time, or the muffling silence of repression.

Mark Doty, Griffin trustee

Biography of Adam Zagajewski

Adam Zagajewski was born in Lvov in 1945, a largely Polish city that became a part of the Soviet Ukraine shortly after his birth. His ethnic Polish family, which had lived for centuries in Lvov, was then forcibly repatriated to Poland. A major figure of the Polish New Wave literary movement of the early 1970s and of the anti-Communist Solidarity movement of the 1980s, Zagajewski is today one of the most well-known and highly regarded contemporary Polish poets in Europe and the United States. His luminous, searching poems are imbued by a deep engagement with history, art, and life. He enjoys a wide international readership, and his poetry survives translation with unusual power. Author Colm Tóibín wrote in The Guardian: “With a sensibility damaged by history, a political conscience deformed by totalitarianism, a mind deeply affected by his study of philosophy, it would be easy to imagine Zagajewski writing veiled protest poetry (which he did in his youth) or poems entirely private and runic, bitter in tone and indecipherable in content, or even descending into shrill silence. He has instead been rescued by a fundamental belief in poetry itself, its autonomous and beautiful power in conflict always with its mundane roots in the visible and quoditian universe, ‘the whole coarse existence of the world’, as he puts it. He has been rescued also by the great pull in his work between a tragic conscience and a voice always on the verge of bursting with comic pleasure. He has been greatly assisted by his love of phrases and his talent for making them, and by a well-stocked mind and, most of the time, a glittering imagination.”

Zagajewski’s most recent books in English are Unseen Hand (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2011); Eternal Enemies (FSG, 2008); and Without End: New and Selected Poems (2002), which was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award. Zagajewski’s other collections of poetry include Mysticism for Beginners (1999), Canvas (1991), and Tremor: Selected Poems (1985). He is also the author of a book of essays and literary sketches, Two Cities: On Exile, History and the Imagination (1995), and of Solidarity, Solitude: Essays.

In his memoir, Another Beauty (2000), Zagajewski writes about growing up in a country “as dreary as the barracks” and documents the artistic and political ferment that occurred in Poland during his youth. Booklist called it an “elegant scrapbook” and said, “Full of pithy and compelling observations on art and society, of luminous descriptions of Krakow and Paris … this is a book to be read once through and returned to often, wherever one happens to open it or in search of a particular passage or statement.”

When, after September 11, The New Yorker published his poem, “Try to Praise the Mutilated World,” on its back page — a rare departure from the cartoons and parodies that usually occupy that space — it resonated with many readers. In an interview in Poets & Writers Magazine, Zagajewski said, “Don’t we use the word poetry in two ways? One: as a part of literature. Two: as a tiny part of the world, both human and pre-human, the part of beauty. So poetry as literature, as language, discovers within the world a layer that has existed unobserved in reality, and by doing so changes something in our life, expands somewhat the space of what we are. So yes, it has the power to restore the mutilated world, even if no statistics ever show it.”

Before his passing, Adam Zagajewski spent part of the year in Krakow, the city he lived in during the 1960s and 70s, and taught in Chicago.

On March 21, 2021 – World Poetry Day – we were deeply saddened to learn of Adam Zagajewski’s passing. As illustrated by the tribute above, as well as his captivating, self-effacing reading during the Griffin Poetry Prize festivities, Zagajewski honoured and delighted us with his charming presence and trenchant yet hopeful words when we celebrated him as our 2016 Griffin Lifetime Recognition award recipient. We will miss his voice as we are grateful for the beautiful poetry and prose – simultaneously down to earth and transcendent – he has left us.

- Adam Zagajewski profile Poetry Foundation

- Adam Zagajewski profile Poetry International Rotterdam

- “Dawn Always Tells Us Something”: On the Poetry of Adam Zagajewski Bookslut

- Lvov story The Guardian

- Adam Zagajewski, Poet of the Past’s Presence, Dies at 75 New York Times

- Acclaimed Polish poet Adam Zagajewski dies at age 75 Toronto Star