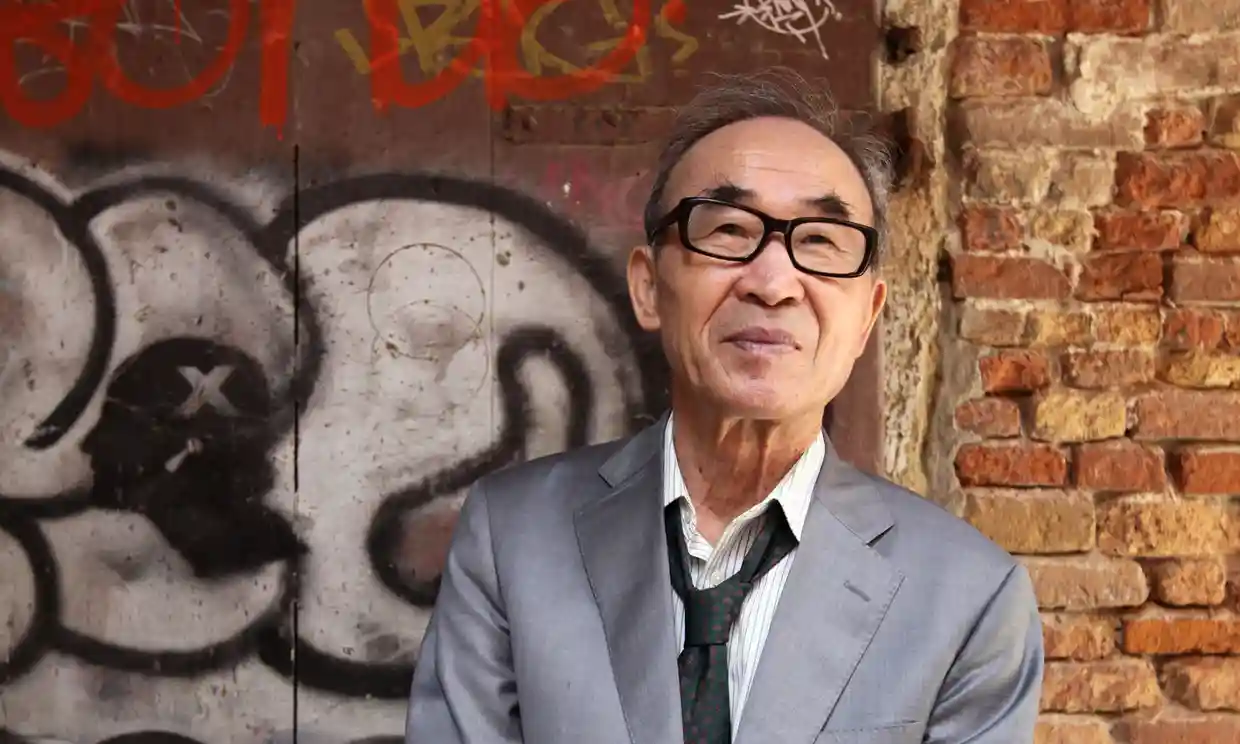

On June 3, the distinguished Korean poet Ko Un was honoured with our Lifetime Recognition Award. Griffin trustee Robert Hass paid tribute to Ko Un and Scott Griffin presented him with his award.

Robert Hass pays tribute to Ko Un

Biography of Ko Un

Ko Un is generally acknowledged to be Korea’s foremost contemporary writer. He is at the same time a poet, an essayist, a novelist, a translator, and a literary critic, with an immense literary achievement consisting of more than 130 books. Still, he says he has more to write in the years to come than he has written so far.

Ko Un was born in 1933 in Kunsan, Chollabuk-do. He began to write poems at an early age. During the horrors of the Korean War (1950-1953) he went through a mental breakdown and made his first attempt at suicide, which was followed by another four attempts over the next 20 years. Before the end of the war he joined a Buddhist monastery and became a monk. For the next decade he practised intense Zen meditation and traveled throughout the country. In 1957 he founded the “Buddhist Newspaper” and began to publish poems, essays, and novels. In 1962, being already widely known as a poet and having served as head monk of several major temples, he left the Buddhist community after publishing a “Resignation Manifesto”.

During the period 1963-1966 he isolated himself in Cheju Island, founding a charity school, teaching Korean and art, writing most beautiful symbolist poems and suffering from severe insomnia and alcohol abuse. In 1967-1973, now back in Seoul, while dedicating himself thoroughly to nihilism, he produced many works. In 1973 he was awakened to the reality of his country by the self-immolation of an uneducated laborer and became engaged in political and social activities opposing the military regime, also joining the struggle for human rights and the labour movement.

After the formation of the Association of Writers for Practical Freedom in 1974, he became its first secretary general. During 1974-1982 he was, many times and for long periods, persecuted by KCIA with arrests, house arrests, detentions, tortures, and imprisonments. In 1980 he was sentenced to 30 years imprisonment. After serving two and a half years, he was set free in a general pardon.

In 1983 he married Sang-Wha Lee, a professor of English literature, at the age of 50, and settled in Ansong, south of Seoul. Two years later their daughter was born. With his marriage began a time of productivity unparalleled in the history of Korean literature – one critic has called it an “explosion of poetry” – in which a seven-volume epic Mountain Paekdu, many volumes of Ten Thousand Lives, a five-volume autobiography, and numerous volumes of poems, essays, and novels poured out. He is often called “The Ko Uns” instead of “Ko Un” by literary critics because of his incredible activity, a volcano of productivity. “He writes poetry as he breathes,” a literary critic once said. “Perhaps he breathes his poems before putting them to paper. I can imagine that his poems spring forth from his enchanting breath rather than from his pen.”

Ko Un was elected Chairman of the Association of the Writers for National Literature and honoured as a resident professor of the graduate school, Kyong-gi University. He was a visiting research scholar at the Yenching Institute of Harvard University and the University of California, Berkeley. He has received many prestigious literary awards in Korea, his books have been translated into more than 15 Asian and European languages, and he has been acclaimed as one of the most important poets of the world. He is now a visiting professor at Seoul National University and the President of the Compilation Committee of the Grand Inter-Korean Dictionary.

Ko Un has written far more than any other Korean poet, and manifested an immense diversity – epigrams of a couple of lines; long discursive poems; epic; pastoral; and even a genre of poems he has himself created, of which Maninbo (Ten Thousand Lives) is the main example, termed popular-historical poetry. He once said that if the quantity of his works did not guarantee the quality of his works he would immediately stop writing.

In the foreword to his poetry collection Sea Diamond Mountain, he says of his sense of poetic creation: “If someone opens my grave a few years after my death, they will find it full, not of my bones, but of poems written in that tomb’s darkness … Am I too attached to poetry? Because my poems exist side-by-side with a farewell to poetry, my attachment is one aspect of a deliverance from poetry.”

The famous American beat poet Allan Ginsberg said of the poet: “Ko Un is a demon-driven Bodhisattva of Korean poetry, exuberant, abundant, obsessed with poetic creation – a magnificent poet, combined of Buddhist cognoscente, passionate political libertarian, and natural historian.”

Poet and peer Robert Hass, who has worked with Ko Un, says: “he is a remarkable poet and one of the heroes of human freedom in this half century, a religious poet who got tangled by accident in the terrible accidents of modern history. But he is somebody who has been equal to the task, a feat rare among human beings.”

If someone opens my grave a few years after my death, they will find it full, not of my bones, but of poems written in that tomb’s darkness.

Ko Un