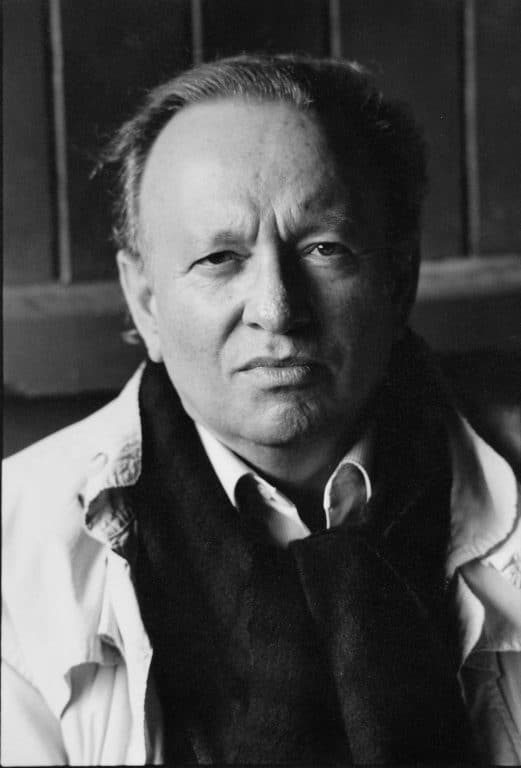

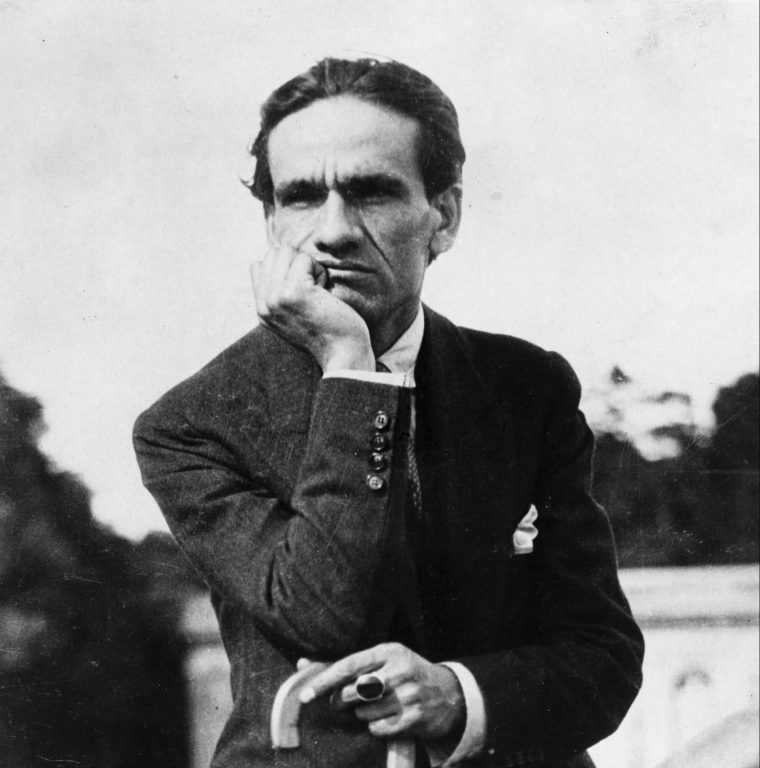

We were sorry to learn this past week of the passing of respected poet and translator Clayton Eshleman. We are grateful for the poetry and translation works he has left us. He was immensely dedicated to poetry and translation throughout his career, with distinguished work on Aimé Césaire, Pablo Neruda, Antonin Artaud and more. His translation of César Vallejo’s work was shortlisted for the 2008 Griffin Poetry Prize, and we are going to revisit one of those powerful pieces this week.

In January, 2019, Poem of the Week considered again how Eshleman beautifully transformed into English the work in Spanish of César Vallejo. That work is encompassed in The Complete Poetry: A Bilingual Edition. In the fall of 2018, we also pondered Eshleman’s work in the poem “Spain, Take This Cup From Me”.

If one is proficient in both Spanish and English, the delight and the challenge of reading work like this is the facility with which one can alternate between the meaning and nuance of the original and translated text. Knowledge of both languages gives one the privilege of assessing the quality of the translation.

The bilingual reader is afforded the luxury of determining if the poem has traveled safely and soundly from one language and culture to another and is still, arguably, poetic. But if one is reading work that has arrived in English from an origin in which one is not conversant, what then? Trust in the translator is essential, not just to employ linguistic accuracy, but to apply cultural sensitivity, historical context and more, along with an ear for the original’s lyricism and music. Here is an interesting collection of reactions to what can and cannot be translated when poetry moves from one language to another.

Ellen Welcker ponders this and more in her 2009 essay “Only Poems Can Translate Poems: On the Impossibility and Necessity of Translation” in The Quarterly Conversation. Her piece includes ruminations by 2016 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted poet Joy Harjo, who performs a startling type of translation in her work by, as a person of Muskogee heritage, not writing in her native tongue but in, as the essay describes it, “the language of her people’s colonizers”. This powerful essay posits:

“In poetry, as well as in translation, there is no ultimate meaning. Indeed, the “trans” in translation and trans-creation indicates that we are always moving across languages, across cultures.”

and concludes:

“As post-colonial translation and trans-creation become bolder and more experimental, the idea of ownership of language falls away. Each newly created text becomes the author’s, and simultaneously becomes the world’s. These poetries are dialogues, conversations. Language becomes three-dimensional as it encompasses more of its history and culture. Poems to be translated are no longer mathematical equations filled with estimations and “equals” signs. As new poetries assert that there can be both “homage and reappropriation,” new methods of translation arise and language is stretched, tested, discovered, and discovered anew.”

When we read poetry in translation, we either trust poetic and linguist guides such as Clayton Eshleman, Susan Wicks, Heather McHugh, Mira Rosenthal, Joanna Trzeciak and more to present us with a faithful rendition of the original work, or we are in a position to critique the quality of their work because we’re conversant in the original and translated languages. Either way, we can appreciate that translators undeniably embark on daunting missions, often crossing thorny terrain, often crossing it alone, to bring us poetry from a place of origin to a new place that still respects and holds precious a work’s roots and essence.

As Welcker observes, “translation and trans-creation are not only about what is lost, but also about new solidarities, built by a fusion of language.”