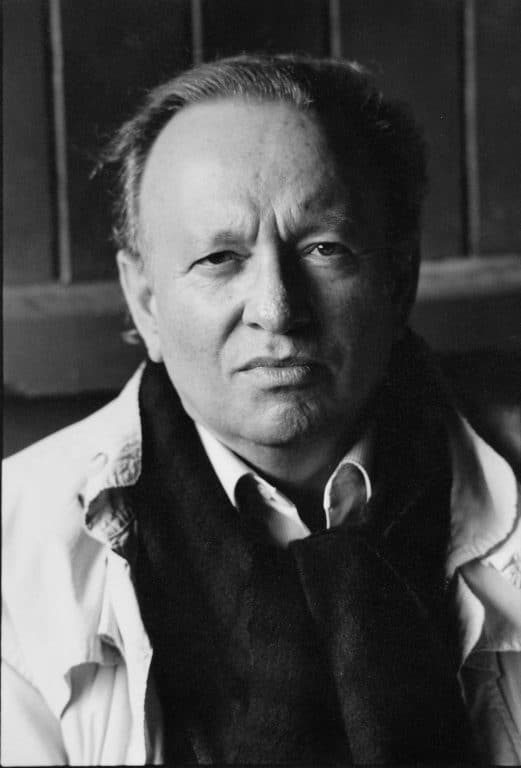

Alan Shapiro captures an unpleasant experience we can all admit to sharing – having to reluctantly enter and avail ourselves of a derelict and dirty restroom facility (washroom, toilet, lavatory or loo). How does he manage to take that experience, not flinch from describing it, but somehow transcend it?

Certainly, he renders the repulsive setting…

Alan Shapiro captures an unpleasant experience we can all admit to sharing – having to reluctantly enter and avail ourselves of a derelict and dirty restroom facility (washroom, toilet, lavatory or loo). How does he manage to take that experience, not flinch from describing it, but somehow transcend it?

Certainly, he renders the repulsive setting and its filthy components accurately, from the towel to the mirror to the sink … to, ahem, the bowl, the seat and the surrounding atmosphere. How does Shapiro keep us reading, even as he’s forcing us to relive visits to places we’d rather forget?

Some interesting repetitions and hints of rhymes seem to propel us forward to … well, we’re not sure what, starting with the clever and resonant lines:

“The present tense

is the body’s past tense

here”

followed by an incantation of the word “hence”, which also rhymes with “scents”, of course.

“Paul

becoming Saul”

intrigues because it suggests something biblical and presumably more elevated in tone than what we’ve confronted so far in this poem. But hold on – didn’t Saul become Paul? What does the reversal mean?

Characterizing the typical graffiti found in places like this as “cave-like scribblings and glyphs” is both whimsical and possibly portentous. What Shapiro contends that it portends is the biggest reversal (or “inversion”, as he also hints at) of all. The immediacy at all levels of the grimy restroom is actually a kind of heaven, and that which is bleached and sanitized and deodorized is the true hell. If he hasn’t convinced all of us, Shapiro has certainly held our attention with this unlikely version of paradise right to the end of his thesis.