The poem “The goat” is an excellent example of the unique ways in which Aisha Sasha John draws the reader into her experiences in her 2018 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted collection I have to live.

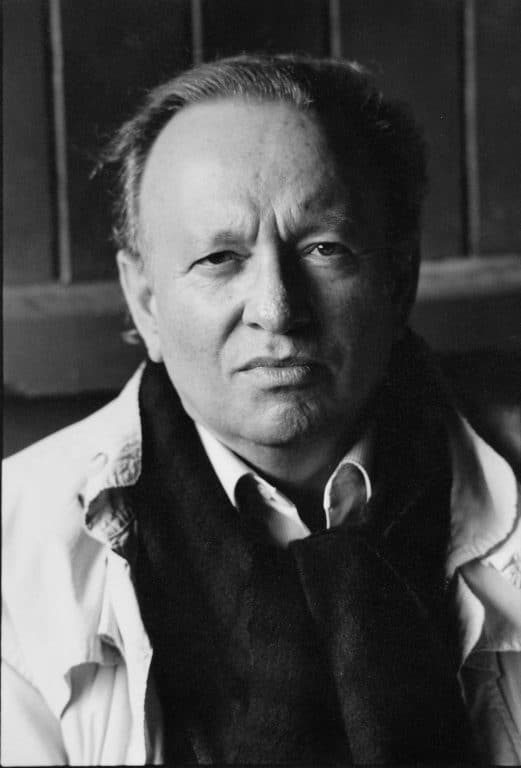

Griffin Poetry Prize judge Ian Williams offered a wonderful overview of what Aisha Sasha John accomplishes in her collection when he introduced her at the 2018 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlist readings:

“Aisha Sasha John delivers a master class in voice. In fact, the voice of her collection I have to live is so masterfully constructed that one can misapprehend it as effortless or easy. But better adjectives might be ‘confident’, ‘assured’, ‘secure in its right to exist and to speak’. Over the course of the book, that voice sustains itself through a number of complex intersections with gender, sexuality and race. In addition to the pleasure of the voice, this collection is also infectious. After reading it the first time, I set it down and found myself quoting it, after just one time. The very title I have to live, according to David B. Hobbs in The Globe and Mail, is ‘repeated enough to become a sort of heartbeat for the collection.’ True, the collection as a whole has a sort of recursive quality that draws you back to itself through some current, some magnetism, some need. One final pleasure is how Aisha Sasha John’s commitment to declarative sentences turn into affirmations. She courts a line between what is tacitly understood and what needs to be stated. It’s hard not to fill in your own name in a poem like this one: ‘He thinks I should be glad because they / Like the idea of Aisha. I am not the idea of Aisha. / I am Aisha. / You I know you / Love the idea of Aisha. / I am not the idea of Aisha. / I am not the idea of Aisha. / I am Aisha.’ Urgent, sincere, confident, unforgettable – here’s Aisha Sasha John and I have to live.”

(You can read the full review Williams mentions in his introduction here.)

Williams remarks on the power of Aisha Sasha John’s use of declarative sentences. If, in real life, someone spoke to you almost exclusively in this fashion, it might quickly become off-putting. The speaker would come across as too focused on self, with no inclusive or at least polite interest in you or others. In poems like “The goat”, the narrator balances her own story and observations with that of a goat who

“has to fucking bray

Because he is alive

And

Tied up.”

That this might be a justification for the narrator’s own tendencies, but that justification is illustrated with this creature, couches it with both acute, even harsh awareness and humility, and maybe even a bit of self-deprecating humour.

The use of proper names in the poem adds a layer of specificity and intimacy to the poem – it’s as if we’re invited to listen in on the narrator’s conversations with her friends – yet simultaneously it excludes us, as we don’t necessarily know who Fadwa and Manuela are. Similarly, the French/English mash-up with which she closes the poem suggests she is simultaneously striving to make her contentions clear, but maybe also striving to obscure them just a bit. What does she mean by

“To scorn you

But not enough to

Not scorn you –

D’accord?”

We are indeed drawn in and intrigued, even though we don’t know for certain if she wants to bring us closer or keep us at arms’ length.