Let’s revisit Joanna Trzeciak’s translation from the Polish of Tadeusz Rozewicz’s poem “Unde malum?” It captures strikingly the age-old philosophical struggle with the problem of evil, how one can reconcile the existence of evil with that of an all knowing, all powerful and benevolent deity. Not only do Rosewicz’s ruminations add to the body of…

Let’s revisit Joanna Trzeciak’s translation from the Polish of Tadeusz Rozewicz’s poem “Unde malum?” It captures strikingly the age-old philosophical struggle with the problem of evil, how one can reconcile the existence of evil with that of an all knowing, all powerful and benevolent deity. Not only do Rosewicz’s ruminations add to the body of thought about this dilemma, but they spark responses in fellow thinkers and poets.

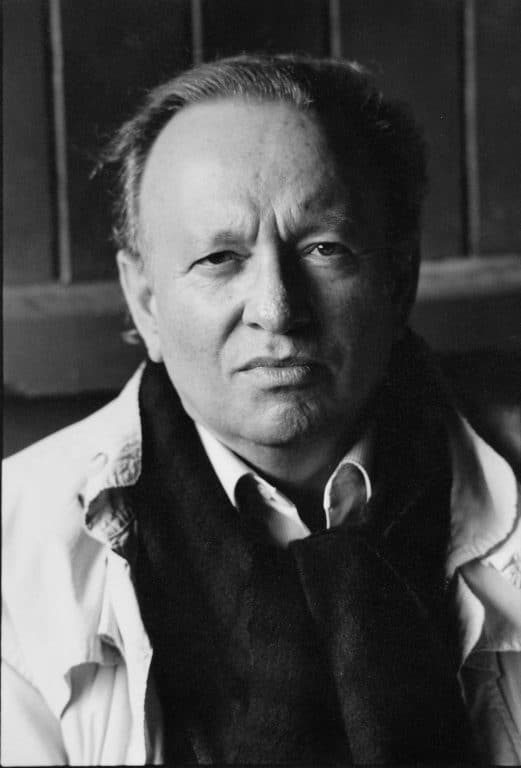

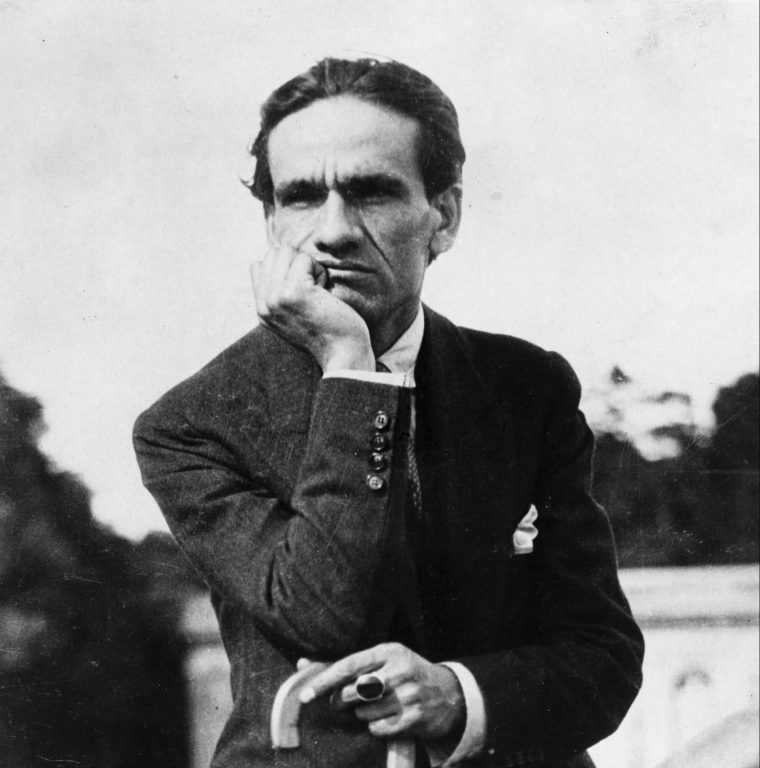

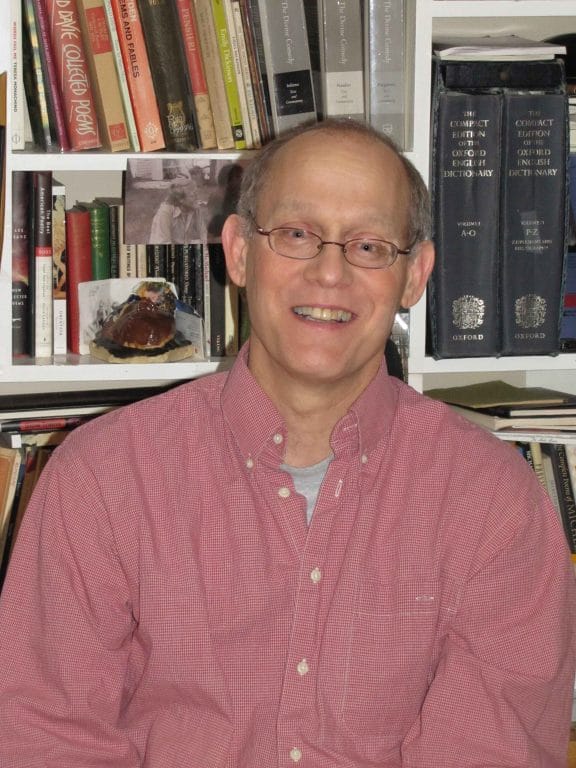

The original version of Rozewicz’s poem in Polish was published in 1998, in a collection entitled zawsze fragment. recycling. Fellow Polish writer Czeslaw Milosz then responded to that poem in Polish, and then it was translated into English and featured in The Guardian in 2001. After you read Joanna Trzeciak’s translation on this page, you can read Milosz’s response here.

The tradition of answer or response poems is a long one, and as one essayist observes, “for the answer-poet the verse exchange represents a means of imposing an alternate outlook upon a contending poetic statement.” This course material also discusses many methods that the answering artist can employ to craft a response to a work that has inspired debate. What do you think of the approach Milosz has taken, and do you think his response is effective?

As Rosewicz, in Trzeciak’s translation, observes:

“human beings are the only beings

who use words

which can serve as tools of crime”

In tandem, Rozewicz/Trzeciak and Milosz also use words as positive tools to advance a challenging subject with poetic conversation.