In the 2019 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted work The Blue Clerk, Dionne Brand scrutinizes in unique and lyrical fashion how writing happens and what it produces, in part through an ongoing dialogue between a poet and a clerk who keeps secure watch over the poet’s work. Along the way, Brand tackles eternal questions around how…

In the 2019 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted work The Blue Clerk, Dionne Brand scrutinizes in unique and lyrical fashion how writing happens and what it produces, in part through an ongoing dialogue between a poet and a clerk who keeps secure watch over the poet’s work. Along the way, Brand tackles eternal questions around how art is realized and received. Verso 32.2 is part of a contemplation of whether or not works can and should be separated from their human, fallible and sometimes cruel creators.

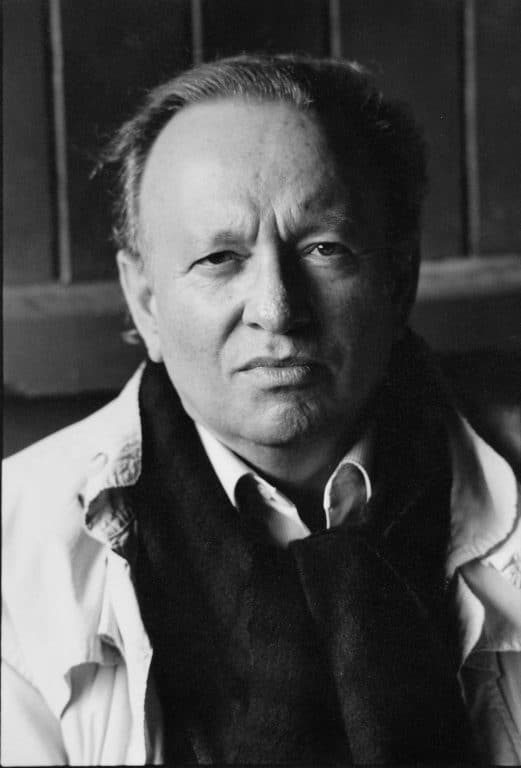

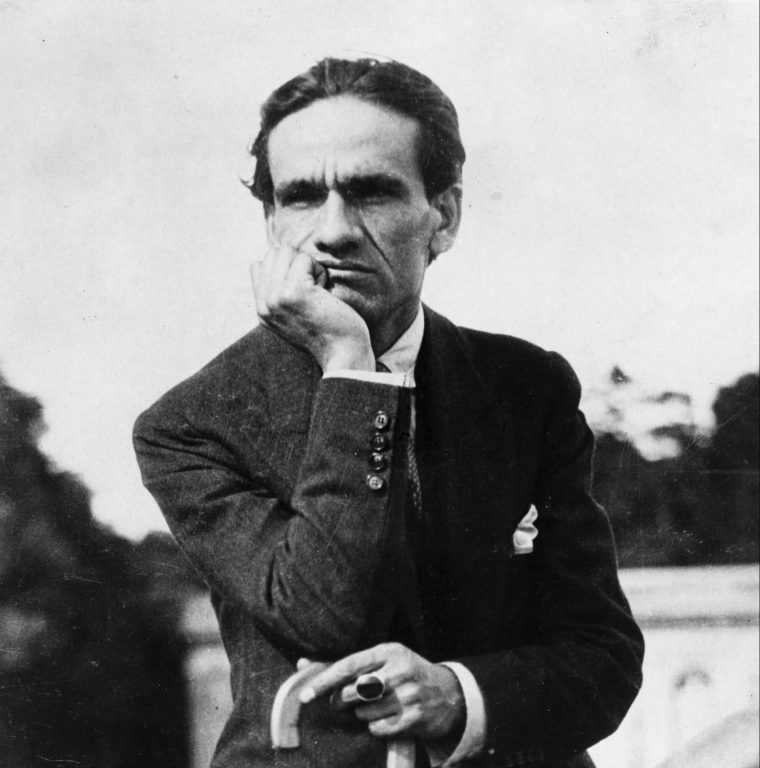

Verso 32.2 is part of a series within The Blue Clerk that references shameful and racist connections in the lives of poet T.S. Eliot and philosopher Plato, as well as philosopher and physician John Locke, whose “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” is mentioned here. Brand’s narrator struggles with how Locke can create a seminal work contemplating the foundation of human knowledge and understanding, and blithely juxtapose that with his involvement and championing of organizations and causes that persecute and harm human beings.

“these identifiers can lie beside each other with no discomfort, apparently.”

the narrator declares with understandably bitter rage and weariness.

“I cannot get past this.”

she declares with heartwrenching bluntness. But when she goes on to state

“I am just a lover with a lover’s weaknesses, with her manifest of heartaches.”

does that mean she still loves Locke’s stirring works? Or can she not get past his heinous acts and associations to still love his work, or can she not get past reconciling the two? If that’s the case, we’re asked as readers to consider whether or not she should …

Contemporary musings on the dilemma of needing to separate the work from the ignoble creator so one can still admire the work can be found everywhere. Recent examples here, here and here illustrate that it is both a constant issue and a perennially unresolved one.

But something more critical than just musing is necessary for what Brand’s narrator raises here, isn’t it? The narrator’s “I am a soft-hearted person” could be construed as ironic, surely. And surely this is no longer an either/or, particularly where the works and achievements, the tributes and monuments to the creators, the explorers but also the oppressors all demand urgent reevaluation.