Carl Phillips is a graduate of Harvard University and the University of Massachusetts. He taught high school Latin for eight years and is the author of twelve books of poetry, including Speak Low (2009) that was a finalist for the National Book Award and Double Shadow (2011), also a finalist for the National Book Award and winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. He has received numerous awards and honours, including the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, the Theodore Roethke Memorial Foundation Award in Poetry, a Lambda Book Award and the Thom Gunn Award for Best Gay Male Poetry, as well as fellowships from the Academy of American Poets, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Guggenheim Foundation, and the Library of Congress. Phillips was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 2006. He teaches at Washington University, in St. Louis, Missouri.

Judges’ Citation

Carl Phillips is a poet of the line and a poet of the sentence, both at once.

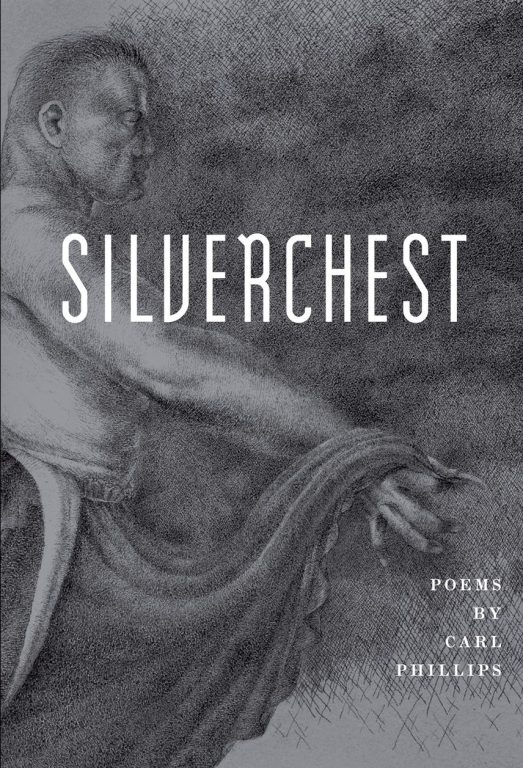

Carl Phillips is a poet of the line and a poet of the sentence, both at once. Rubbing these two intangible structures – one musical, the other linguistic – against one another is an ancient way of kindling verbal and intellectual fire, and Phillips does it in poem after poem with casual mastery. The lines are carved in low relief, shaped by internal assonance, not by end-rhyme, while the sentences trace a perfectly grammatical yet occasionally dizzying switchback trail, using the standard resources of prose to climb far beyond the prosaic domain. Phillips’s Silverchest consists in large part of reflections on a love affair gone bad. It is a gay male love affair in this case, but the anguish, the self-doubt, the sense of abandonment and loss, are captured here with a tenderness, depth, and precision that can dance through sociocultural fences as easily as deer can dance across the grass. Silverchest speaks, as great books do, out of its own profound particularity, to and for something wordless and shared by us all.

Selected poems

by Carl Phillips

There’s a weed whose name I’ve meant all summer

to find out: in the heat of the day, dangling pods hardly

worth the noticing; in the night, blue flowers . . . It’s as if

a side of me that he’d forgotten had forced into the light,

briefly, a side of him that I’d never seen before, and now

I’ve seen it. It is hard to see anyone who has become

like your own body to you. And now I can’t forget.

Copyright © 2013 by Carl Phillips, Silverchest, Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Just the Wind for a Sound, Softly

Sure, there’s a spell the leaves can make, shuddering,

and in their lying suddenly still again – flat, and still,

like time itself when it seems unexpectedly more

available, more to lose therefore, more to love, or

try to …

But to look up from the leaves, remember,

is a choice also, as if up from the shame of it all,

the promiscuity, the seeing-how-nothing-now-will-

save-you, up to the wind-stripped branches shadow-

signing the ground before you the way, lately, all

the branches seem to, or you like to say they do,

which is at least half of the way, isn’t it, toward

belief – whatever, in the end, belief

is … You can

look up, or you can close the eyes entirely, making

some of the world, for a moment, go away, but only

some of it, not the part about hurting others as the one

good answer to being hurt, and not the part that can

at first seem, understandably, a life in ruins, even if –

refusing ruin, because you

can refuse – you look

again, down the steep corridor of what’s just another

late winter afternoon, dark as night already, dark

the leaves and, darker still, the door that, each night,

you keep meaning to find again, having lost it, you had

only to touch it, just once, and it bloomed wide open …

Copyright © 2013 by Carl Phillips

My Meadow, My Twilight

Never mind the parts that came later, with all

the uselessness, as usual, of hindsight: regret’s

what it has to be, in the end, in which way it is

like death, any bowl of sliced-fresh-from-the-tree

stolen pears, this body that stirs

or fails to, as I

turn away, meaning Make it yours, or Hold tight,

or I begin to think maybe you were right – that

there’s nothing, after … thought whether or not like

one of those moments just past having woken to

yet another stranger,

how the world can seem

to have completely stopped when, finally, it’s just

a stillness – who can say? First I envied them,

then I came to love them for it, how the stars each

day become again invisible, while going nowhere.

Copyright © 2013 by Carl Phillips

Now Rough, Now Gentle

Squalor of leaves. November. A lone

hornets’ nest. Paper wasps. Place where

everything that happens is as who says it will,

because. As in Why shouldn’t we have

come to this, why not, this far, this

close to

that below-zero where we almost

forget ourselves, rise at last unastonished

at the wreckery of it, what the wreckage

somedays can seem all along to have

been mostly, making you wonder what fear

is for, what prayer is, if not the first word

and not the last one either, if it changes

nothing of what you are still, black stars,

black

scars, crossing a field that you’ve

crossed before, holding on, tight, though

careful, for you must be careful, so easily

torn is the veil diminishment comes

down to as it lifts and falls, see it falling,

now it lifts again, why do we love, at all?

Copyright © 2013 by Carl Phillips