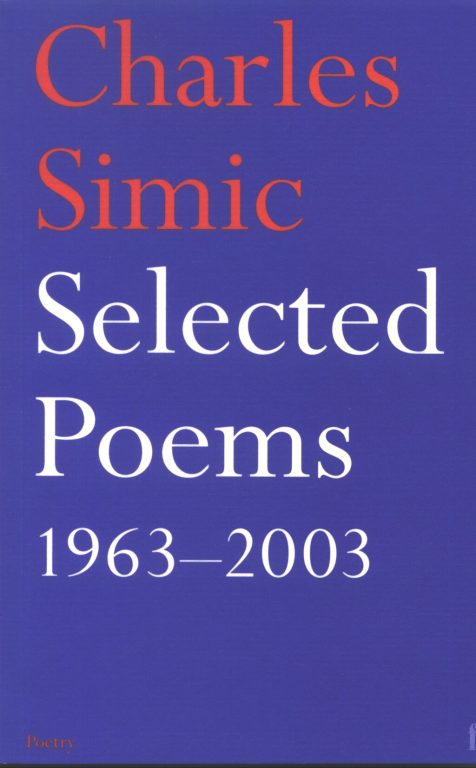

In his prolific career, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Charles Simic published seven books of essays, a memoir, numerous translations, and over twenty collections of poetry. Born in 1938 in Belgrade Yugoslavia, Simic immigrated to the United States in 1952 and saw his first poems published in 1959. In 1961 he was drafted into the US Army and in 1966 earned his Bachelor’s degree at New York University, publishing his first full-length collection of poems What the Grass Says in 1967. Simic published more than 60 books in the United States including No Land in Sight (2022), The Lunatic (2015), New and Selected Poems: 1962-2012 (2013), My Noiseless Entourage (2005), Jackstraws (Notable Book of the Year in the New York Times 1999), Walking the Black Cat (finalist for the National Book Award in Poetry 1996), A Wedding in Hell (1994), Hotel Insomnia (1992), The World Doesn’t End: Prose Poems (for which he received the Pulitzer for Poetry in 1990), Selected Poems: 1963 – 1983 (1990), and Unending Blues (1986). He also published many translations of French, Serbian, Croatian and Macedonian and Slovenian poetry and has twice won the Pen International Translation Award.

Amongst his many accomplishments and accolades, Simic was the Guest Editor of The Best American Poetry 1992, was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 2000, and received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. Simic was our 2005 International Griffin Poetry Prize winner and was selected by the Griffin trustees as a judge for the 2007 Griffin Poetry Prize.

Simic was the 2007 recipient of the Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets. The $100,000 (US) prize recognizes outstanding and proven mastery in the art of poetry. On the same day in August, 2007 that Simic received this award, the U.S. Library of Congress announced that he had been chosen as the new U.S. Poet Laureate.

From 1973-2023, Simic lived in New Hampshire where he was Professor of English at the University of New Hampshire.

We were deeply saddened by the announcement of Simic’s death on January 9, 2023.

Judges’ Citation

Simic is something of a magician, a conjuror. Out of nothing it seems, out of thin air, the poems appear before our eyes.

Simic is something of a magician, a conjuror. Out of nothing it seems, out of thin air, the poems appear before our eyes. One apparently casual observation leads to another, and suddenly, exponentially, we are spellbound. It is a trick many have tried to imitate but few have achieved. At the centre of Simic’s art is a disarming, deadpan precision, which should never be mistaken for simplicity. Everything appears pared back to the solid and the essential, and it is this economy of vocabulary and clarity of diction which have made his poetry so portable and so influential wherever it is published. Simic is one of the few poets of our time to achieve both critical and popular acclaim; he is genuinely quotable, and it is entirely possible that some of his phrases and lines will lodge in the common memory. Without any hint of loftiness, then, and from a position which is entirely his own, Simic manages to speak to the many and not just the few.

Selected poems

by Charles Simic

I grew up bent over

a chessboard.

I loved the word endgame.

All my cousins looked worried.

It was a small house

near a Roman graveyard.

Planes and tanks

shook its windowpanes.

A retired professor of astronomy

taught me how to play.

That must have been in 1944.

In the set we were using,

the paint had almost chipped off

the black pieces.

The white King was missing

and had to be substituted for.

I’m told but do not believe

that that summer I witnessed

men hung from telephone poles.

I remember my mother

blindfolding me a lot.

She had a way of tucking my head

suddenly under her overcoat.

In chess, too, the professor told me,

the masters play blindfolded,

the great ones on several boards

at the same time.

Copyright © Charles Simic, 2004

Prodigy

Poet of the dead leaves driven like ghosts,

Driven like pestilence-stricken multitudes,

I read you first

One rainy evening in New York City,

In my atrocious Slavic accent,

Saying the mellifluous verses

From a battered, much-stained volume

I had bought earlier that day

In a second-hand bookstore on Fourth Avenue

Run by an initiate of the occult masters.

The little money I had being almost spent,

I walked the streets my nose in the book.

I sat in a dingy coffee shop

With last summer’s dead flies on the table.

The owner was an ex-sailor

Who had grown a huge hump on his back

While watching the rain, the empty street.

He was glad to have me sit and read.

He’d refill my cup with a liquid dark as river Styx.

Shelley spoke of a mad, blind, dying king;

Of rulers who neither see, nor feel, nor know;

Of graves from which a glorious Phantom may

Burst to illumine our tempestuous day.

I too felt like a glorious phantom

Going to have my dinner

In a Chinese restaurant I knew so well.

It had a three-fingered waiter

Who’d bring my soup and rice each night

Without ever saying a word.

I never saw anyone else there.

The kitchen was separated by a curtain

Of glass beads which clicked faintly

Whenever the front door opened.

The front door opened that evening

To admit a pale little girl with glasses.

The poet spoke of the everlasting universe

Of things … of gleams of a remoter world

Which visit the soul in sleep …

Of a desert peopled by storms alone …

The streets were strewn with broken umbrellas

Which looked like funereal kites

This little Chinese girl might have made.

The bars on MacDougal Street were emptying.

There had been a fist fight.

A man leaned against a lamp post arms extended as if crucified,

The rain washing the blood off his face.

In a dimly lit side street,

Where the sidewalk shone like a ballroom mirror

At closing time—

A well-dressed man without any shoes

Asked me for money.

His eyes shone, he looked triumphant

Like a fencing master

Who had just struck a mortal blow.

How strange it all was … The world’s raffle

That dark October night …

The yellowed volume of poetry

With its Splendors and Glooms

Which I studied by the light of storefronts:

Drugstores and barbershops,

Afraid of my small windowless room

Cold as a tomb of an infant emperor.

Copyright © 2005 by Charles Simic, Selected Poems: 1963-2003 (Faber and Faber)

Shelley

The great labor was always to efface oneself,

Reappear as something entirely different:

The pillow of a young woman in love,

A ball of lint pretending to be a spider.

Black boredoms of rainy country nights

Thumbing the writings of illustrious adepts

Offering advice on how to proceed with the transmutation

Of a figment of time into eternity.

The true master, one of them counseled,

Needs a hundred years to perfect his art.

In the meantime, the small arcana of the frying pan,

The smell of olive oil and garlic wafting

From room to empty room, the black cat

Rubbing herself against your bare leg

While you shuffle toward the distant light

And the tinkle of glasses in the kitchen.

Copyright © 2004

The Lives of the Alchemists

The obvious is difficult

To prove. Many prefer

The hidden. I did, too.

I listened to the trees.

They had a secret

Which they were about to

Make known to me–

And then didn’t.

Summer came. Each tree

On my street had its own

Scheherazade. My nights

Were a part of their wild

Storytelling. We were

Entering dark houses,

Always more dark houses,

Hushed and abandoned.

There was someone with eyes closed

On the upper floors.

The fear of it, and the wonder,

Kept me sleepless.

The truth is bald and cold,

Said the woman

Who always wore white.

She didn’t leave her room.

The sun pointed to one or two

Things that had survived

The long night intact.

The simplest things,

Difficult in their obviousness.

They made no noise.

It was the kind of day

People described as “perfect.”

Gods disguising themselves

As black hairpins, a hand-mirror,

A comb with a tooth missing?

No! That wasn’t it.

Just things as they are,

Unblinking, lying mute

In that bright light–

And the trees waiting for the night.

Copyright © Charles Simic, 2004