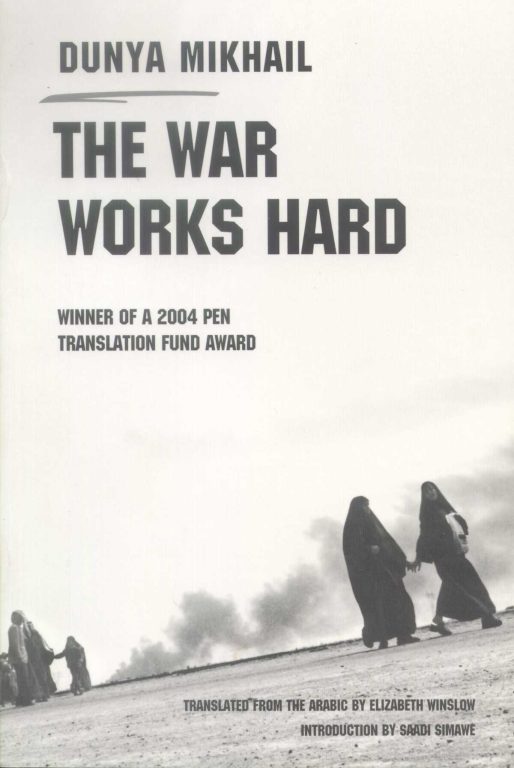

Born in Iraq in 1965, Dunya Mikhail worked as Literary Editor for The Baghdad Observer. Facing increasing threats and harassment from the Iraqi authorities for her writings, she fled Iraq in the late 1990s and studied Near Eastern Studies at Wayne State University. In 2001, she was awarded the UN Human Rights Award for Freedom of Writing. Mikhail has published four collections of poetry in Arabic (she speaks and writes in Arabic, Aramaic, and English), and one lyrical multi-genre text, The Diary of a Wave Outside the Sea. She currently lives in Michigan.

Judges’ Citation

These are political poems without political rhetoric, Arabic poems without Arabic poetical flourishes, an exile’s letter with neither nostalgia nor self-pity, an excavation of the ruins of her homeland

We know that Dunya Mikhail was raised in Saddam’s Iraq and sent into exile to follow the news of its devastation from afar. So the very first line of The War Works Hard comes as a surprise: ‘What good luck!’ The second line crystallizes both the contemporary reality and Mikhail’s sensibility: ‘She has found his bones.’ In her poems, war is a monstrous fact of ordinary life, and her particular skill is the invention of unadorned images that capture the often unexpected human responses. Brecht wrote, ‘We’d all be human if we could,’ and Mikhail, despite all the contrary evidence, shows that we can, and sometimes are. These are political poems without political rhetoric, Arabic poems without Arabic poetical flourishes, an exile’s letter with neither nostalgia nor self-pity, an excavation of the ruins of her homeland where the Sumerian goddess Inana is followed on the next page by the little American devil Lynndie England. In Elizabeth Winslow’s perfect translations, poetry takes on its ancient function of restoring meaning to the language. Here is the war in Iraq in English without a single lie.

Selected poems

by Dunya Mikhail

How magnificent the war is!

How eager

and efficient!

Early in the morning,

it wakes up the sirens

and dispatches ambulances

to various places,

swings corpses through the air,

rolls stretchers to the wounded,

summons rain

from the eyes of mothers,

digs into the earth

dislodging many things

from under the ruins …

Some are lifeless and glistening,

others are pale and still throbbing …

It produces the most questions

in the minds of children,

entertains the gods

by shooting fireworks and missiles

into the sky,

sows mines in the fields

and reaps punctures and blisters,

urges families to emigrate,

stands beside the clergymen

as they curse the devil

(poor devil, he remains

with one hand in the searing fire) …

The war continues working, day and night.

It inspires tyrants

to deliver long speeches,

awards medals to generals

and themes to poets.

It contributes to the industry

of artificial limbs,

provides foods for flies,

adds pages to the history books,

achieves equality

between killer and killed,

teaches lovers to write letters,

accustoms young women to waiting,

fills the newspapers

with articles and pictures,

builds new houses

for the orphans,

invigorates the coffin makers,

gives grave diggers

a pat on the back

and paints a smile on the leader’s face.

The war works with unparalleled diligence!

Yet no one gives it

a word of praise.

Copyright © 2006 Elizabeth Winslow

The War Works Hard

the Arabic written by Dunya Mikhail