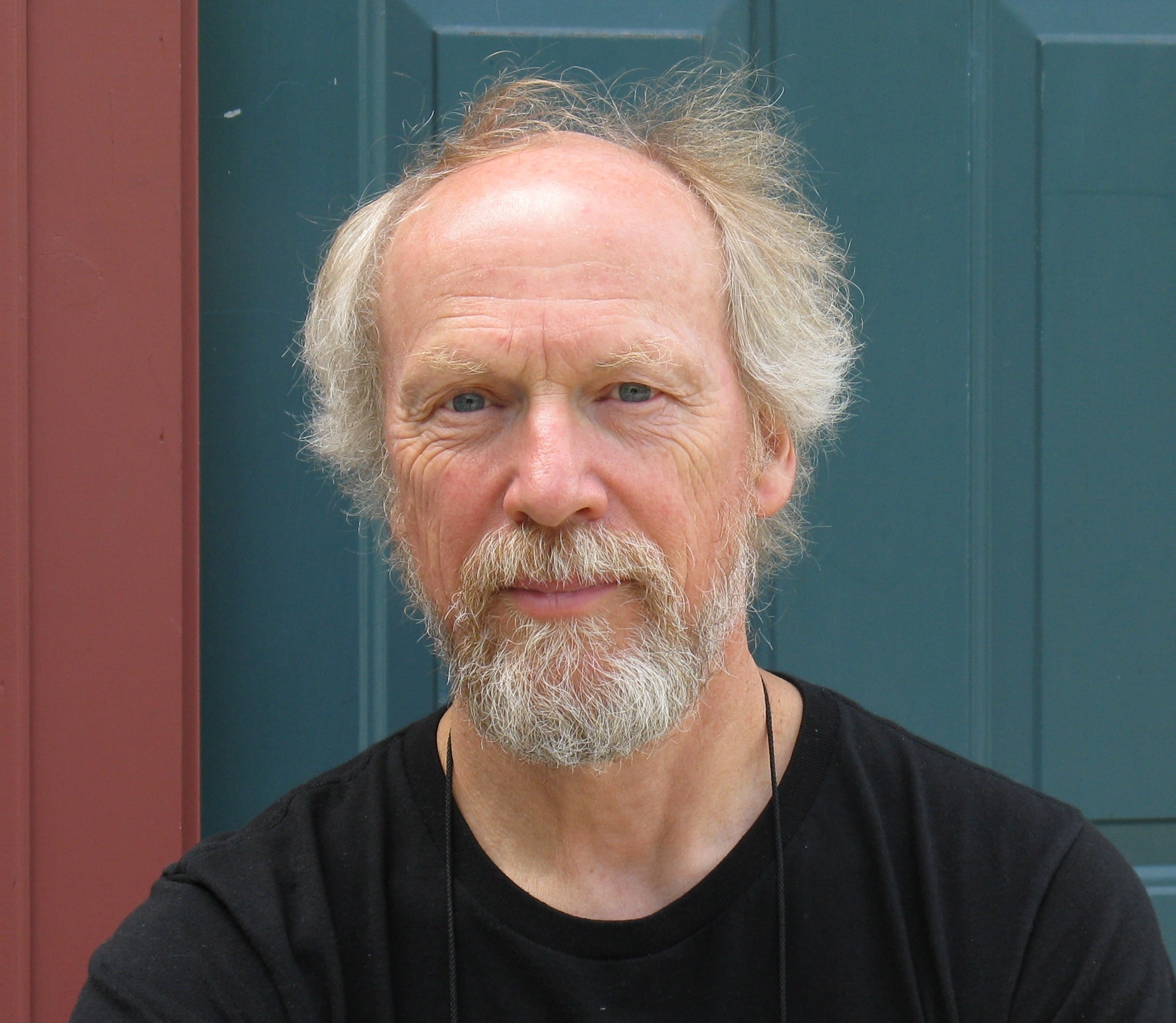

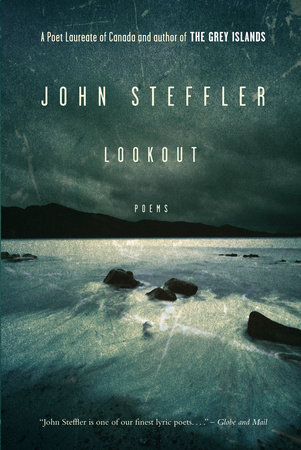

John Steffler was the Parliamentary Poet Laureate of Canada from 2006 to 2008. His previous books of poetry include The Grey Islands, That Night We Were Ravenous, winner of the Atlantic Poetry Prize, and Helix: New and Selected Poems, winner of the Newfoundland and Labrador Poetry Prize. Steffler is also the author of the award-winning novel The Afterlife of George Cartwright.

Judges’ Citation

The playful spontaneity that enlivens John Steffler’s Lookout moves through the poems like wind, revealing both their flexibility and their sturdiness.

The playful spontaneity that enlivens John Steffler’s Lookout moves through the poems like wind, revealing both their flexibility and their sturdiness. With a passionate naturalist’s trained and ever-curious eye, Steffler is interested in what happens both in and out of sight. In language that ranges from affable story-telling to tough, spare, startling lyrics, he probes the complex collisions between Nature and humankind without inflicting upon his subject any of the ecological ranting, self-dramatizing grief, or faux-mysticism that infects so much contemporary ‘nature poetry.’ Modest, plainspoken, and unsentimental in stance, his poems are at the same time untethered to the literal, which allows for sudden and unnerving swerves, poems that decisively and unpredictably break the membrane between realms, as when a vole with ‘a laugh like a snowplow’s blade’ begins to speak, or rifts appear in a loved one’s memory, allowing reality and fantasy, past and present, to dissolve into one another. Steffler’s quality of attention is so fierce and so assured that we trust it to lead us into new and often unsettling territory. In Lookout, his masterful inter-leaving of physical, philosophical, and psychological worlds entices us into a dream of wakefulness we recognize as our own.

Selected poems

by John Steffler

***

The neighbour’s lawn mower roars and recedes.

My mother sleeps on the loveseat, my father

on the couch. I shake out mats in the blinding

porch, gather grey tea towels for the laundry.

My father bustles stiffly out to plug in

the kettle, comes up from the cellar with chunks

of maple, measuring, figuring – how to make

wooden nuts and bolts – then is suddenly

sunk in an armchair, open-mouthed asleep,

while June sunlight storms through the house.

***

I ask about the empty mirror frame on the kitchen

wall. My father glances at me and away, looking

reluctant, caught. Then speaks with odd formality,

doggedly, against some current of shyness or disbelief

or sorrow or fear. He says while they were having

lunch there at the table a few weeks ago they heard

a loud bang like a gunshot close by. He looked around

and found the mirror down on the floor, its heavy glass

split up the middle. “You try to get that off of there,”

he points to the empty frame. A slotted hole in its back

locks the frame tight to a round-headed screw set deep

in a wall stud. I lift and slowly work it free, then press it

back into place, centred, anchored. Enclosed blank

wall. “There’s no way that could have come off

by itself,” he says, bare-headed under low dark cloud.

***

Curled on the loveseat under a blanket

much of each day, sleeping or merely

still, her open eyes travelling the room.

She never grieves for herself, never

stands apart disowning or lamenting

the ruin, but sometimes terrors sweep

through her, weightless spinning and inner

sleets, and she sits shaking, calling out that

she’s falling, and my father or I hold her

trying to save her from deep space.

Copyright © 2010 by John Steffler

from Once

An envelope with your rounded printing. I take out

a card of Henri Rousseau’s Child with Doll –

the stocky worried girl in a red dress, clutching

a worried doll, listening, knowing the whole

landscape is going to erupt through her, life

will depend on her –

then your twelve-week

ultrasound with its five night-blue images

framed in calibrations and ID.

I have albums tracing your quick expressions back

to your infancy, but here I’m looking at moonlight

falling into an excavated grave. Or is it

a distant galaxy? The small gathering bones

glow where faint light picks them out,

a constellation of vertebrae. Hubble

portrait. Reverse grave.

What a woman holds –

river of earth from the Milky Way, where we hatch,

to which we return. From my unwinding whorl I’m looking

through your night sky at forming stars.

Inside those I can almost see smaller stars.

Copyright © 2010 by John Steffler

Mail from My Pregnant Daughter

Wind off the Strait of Belle Isle rakes

the cape clean. Anything wanting to live here

finds it enjoys crouching in a still pocket

behind a rock (eight months of the year

a white drift) where once in a while a companion

will tumble in: an ant’s leg or cinquefoil leaf.

Just arrived is a scuffed mountain avens seed,

which in the next rain might burst its seams and

help pack the small summer room with green, except

for the week in July when it will parody snow.

Leif Eriksson dropped the erratic fact

of his briefly inhabited outpost here,

and now the fascination of tourists gusts

over the ancient site, their exclamations

and money tumble into the shadow it casts

along Route 436, feeding a clump

of restaurants, gift shops, B&Bs, new

bright-painted homes. The local people want

more boulders like L’Anse aux Meadows, more

nooks where money drifts in, especially now

that the Strait is raked clean of cod.

Copyright © 2010 by John Steffler