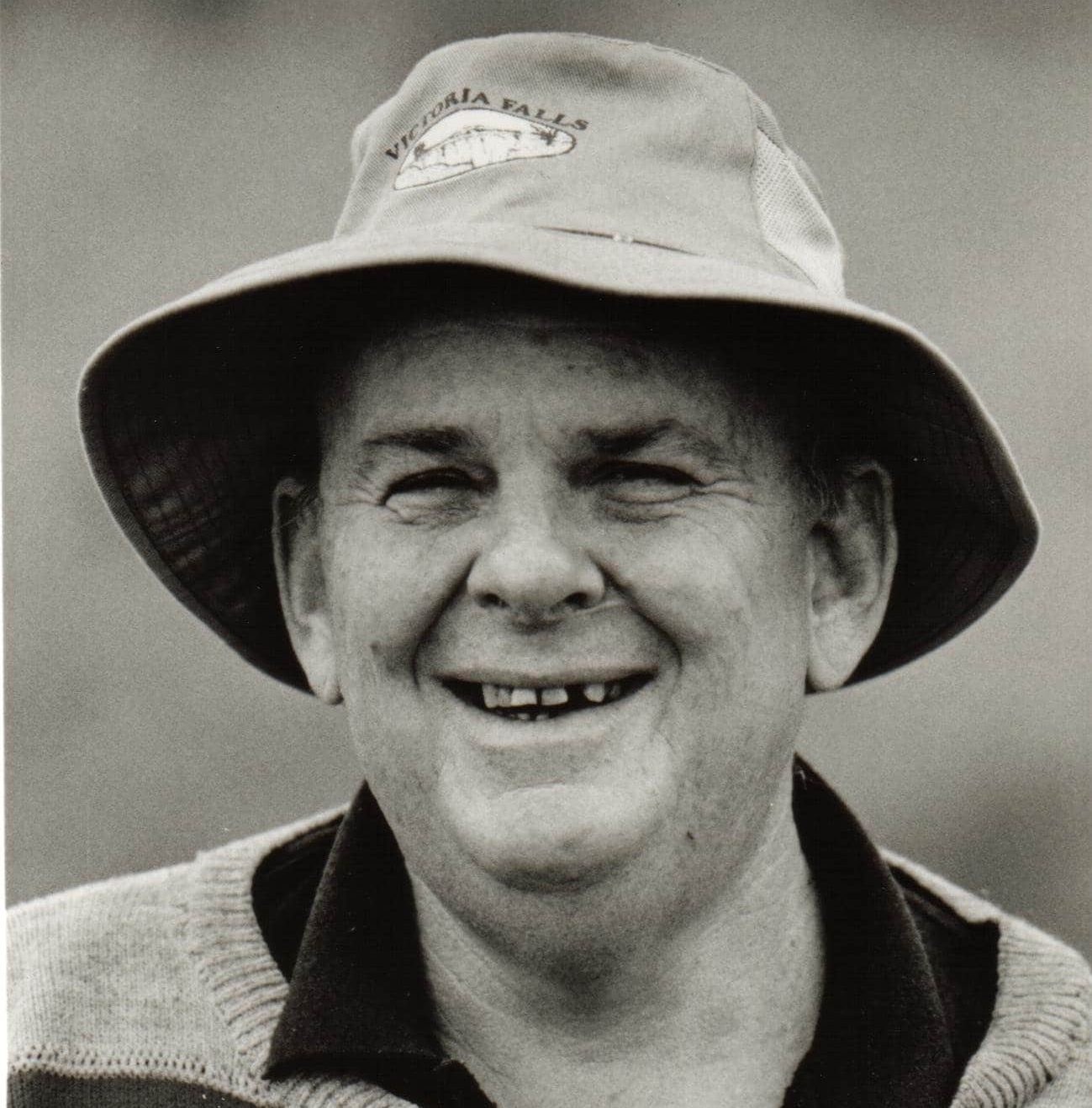

Australia-born Les Murray is the author of 23 titles published in Australia and several in the U.S. and England, including The Vernacular Republic (1982), The Daylight Moon (1988), The Rabbiter’s Bounty: Collected Poems (1991), The Boys Who Stole the Funeral Sequence (1991), Dog Fox Field (1992), Translations from the Natural World (1992), Subhuman Redneck Poems (1997), Fredy Neptune: A Novel in Verse (1999), Learning Human (2000) – Griffin Poetry Prize Shortlisted Book in 2001 – and Conscious and Verbal (2001), voted a Notable Book for 2001 by the American Library Association. Selected prose includes The Quality of Sprawl and A Working Forest. His latest book, Bi-Plane Houses, was published in the spring of 2006.

He has won the T.S. Eliot Prize and has been honoured by the Australian government with the Medal of the Order of Australia for his services to literature. He has been elected an Honorary Fellow by the Australian Academy of the Humanities and was awarded the prestigious Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry in 1998. In addition, he has won numerous National Book Council Awards in Australia, the Australian National Poetry Award, and the Australian Literary Society Gold Medal (1987), among others. He lives on the coast of New South Wales.

The Griffin Trust For Excellence In Poetry is saddened to learn of Les Murray’s passing on April 29, 2019. Among the close to 30 books he published over 40 years, we were honoured to have two of his works grace the 2001 and 2002 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlists. We offer our deepest sympathies to his loved ones.

- 2002

- 2001

Judges’ Citation

A generous selection of poems, written over a period of thirty-five years by the preeminent Australian poet of the late twentieth century.

A generous selection of poems, written over a period of thirty-five years by the preeminent Australian poet of the late twentieth century. Les Murray has a sure touch with the long leisurely poem, written in panavision and what he celebrates in ‘The Quality of Sprawl!’ ‘Sprawl is doing your farming by aeroplane, roughly, /or driving a hitchhiker that extra hundred miles home.’ Murray is also good on the Polaroid snapshot – of an oyster, for instance, with its ‘bloodless sheep’s eye.’ Whether he’s running a marathon or the hundred meters, Murray gives us beauty and bounty in equal measures.

Judges’ Citation

Conscious and Verbal, the title of the latest book – the eighth in little over a decade – by Les Murray, is taken from a hospital press release, informing Australians that their great national poet, after three weeks at death’s door with sudden catastrophic liver failure, was on the mend.

Conscious and Verbal, the title of the latest book – the eighth in little over a decade – by Les Murray, is taken from a hospital press release, informing Australians that their great national poet, after three weeks at death’s door with sudden catastrophic liver failure, was on the mend. One can hear the deprecating giggle, the understatement, in the phrase once Murray adopted it as a title. It is a typically rich and varied performance. What Murray can do is to write interestingly and characteristically about anything and everything; his imagination is fired by any sort of subject: city and country, staying at home or travelling abroad, memory and history, the present or the future, satire or hymn, culture or nature. Here, as well as the poem of his survival – called ‘travels with John Hunter’ (‘I was sped down a road/ of treetops and fishing-rod lightpoles/ towards the three persons of God/ and the three persons of John Hunter/ Hospital. Who said We might lose this one.’ – calm and witty and inventive, there are poems in Conscious and Verbal on the joys of libraries and swimming pools, on poetry and oysters, and Harley Davidsons. If you had to choose a poet to save your life, you could do worse than choose Les Murray.

Selected poems

by Les Murray

The civil white-pawed dog who’d strain

to make speech-like sounds to his humans

lies buried in the soil of a slope

that he’d tear down on his barking runs.

He hated thunder and gunshot

and would charge off to restrain them.

A city dog too alive for backyards,

we took him the pound’s Green Dream

but now his human name melts off him;

he’ll rise to chase fruit bats and bees;

the coral tree and the African tulip

will take him up, and the prickly tea trees.

Our longhaired cat who mistook him

for an Alsatian flew up there full tilt

and teetered in top twigs for eight days

as a cloud, distilling water with its pelt.

The cattle suspect the Dog lives

but three kangaroos stood in our pasture

this daybreak, for the first time in memory,

eared gazing wigwams of fur.

Copyright © 2001 by Les Murray

A Dog’s Elegy

All me are standing on feed. The sky is shining.

All me have just been milked. Teats all tingling still

from that dry toothless sucking by the chilly mouths

that gasp loudly in in in, and never breathe out.

All me standing on feed, move the feed inside me.

One me smells of needing the bull, that heavy urgent me,

the back-climber, who leaves me humped, straining, but light

and peaceful again, with crystalline moving inside me.

Standing on wet rock, being milked, assuages the calf-sorrow in me.

Now the me who needs mounts on me, hopping, to signal the bull.

The tractor comes trotting in its grumble; the heifer human

bounces on top of it, and cud comes with the tractor,

big rolls of tight dry feed: lucerne, clovers, buttercup, grass,

that’s been bitten but never swallowed, yet is cud.

She walks up over the tractor and down it comes, roll on roll

and all me following, eating it, and dropping the good pats.

The heifer human smells of needing the bull human

and is angry. All me look nervously at her

as she chases the dog me dream of horning dead: our enemy

of the light loose tongue. Me’d jam him in his squeals.

Me, facing every way, spreading out over feed.

One me is still in the yard, the place skinned of feed.

Me, old and sore-boned, little milk in that me now,

licks at the wood. The oldest bull human is coming.

Me in the peed yard. A stick goes out from the human

and cracks, like the whip. Me shivers and falls down

with the terrible, the blood of me, coming out behind an ear.

Me, that other me, down and dreaming in the bare yard.

All me come running. It’s like the Hot Part of the sky

that’s hard to look at, this that now happens behind wood

in the raw yard. A shining leaf, like off the bitter gum tree

is with the human. It works in the neck of me

and the terrible floods out, swamped and frothy. All me make the Roar,

some leaping stiff-kneed, trying to horn that worst horror.

The wolf-at-the-calves is the bull human. Horn the bull human!

But the dog and the heifer human drive away all me.

Looking back, the glistening leaf is still moving.

All of dry old me is crumpled, like the hills of feed,

and a slick me like a huge calf is coming out of me.

The carrion-stinking dog, who is calf of human and wolf,

is chasing and eating little blood things the humans scatter,

and all me run away, over smells, toward the sky.

Copyright © 2000 by Les Murray

The Cows on Killing Day

Sprawl is the quality

of the man who cut down his Rolls-Royce

into a farm utility truck, and sprawl

is what the company lacked when it made repeated efforts

to buy the vehicle back and repair its image.

Sprawl is doing your farming by aeroplane, roughly,

or driving a hitchhiker that extra hundred miles home.

It is the rococo of being your own still centre.

It is never lighting cigars with ten-dollar notes:

that’s idiot ostentation and murder of starving people.

Nor can it be bought with the ash of million-dollar deeds.

Sprawl lengthens the legs; it trains greyhounds on liver and beer.

Sprawl almost never says Why not? with palms comically raised

nor can it be dressed for, not even in running shoes worn

with mink and a nose ring. THat is Society. That’s Style.

Sprawl is more like the thirteenth banana in a dozen

or anyway the fourteenth.

Sprawl is Hank Stamper in Never Give an Inch

bisecting an obstructive official’s desk with a chainsaw.

Not harming the official. Sprawl is never brutal

though it’s often intransigent. Sprawl is never Simon de Montfort

at a town-storming: Kill them all! God will know his own.

Knowing the man’s name this was said to might be sprawl.

Sprawl occurs in art. THe fifteenth to twenty-first

lines in a sonnet, for example. And in certain paintings;

I have sprawl enough to have forgotten which paintings.

Turner’s glorious Burning of the Houses of Parliament

comes to mind, a doubling bannered triumph of sprawl –

except, he didn’t fire them.

Sprawl gets up the nose of many kinds of people

(every kind that comes in kinds) whose futures don’t include it.

Some decry it as criminal presumption, silken-robed Pope Alexander

dividing the new world between Spain and Portugal.

If he smiled in petto afterwards, perhaps the thing did have sprawl.

Sprawl is really classless, though. It’s John Christopher Frederick Murray

asleep in his neighbours’ best bed in spurs and oilskins

but not having thrown up;

sprawl is never Calum who, drunk, along the hallways of our house,

reinvented the Festoon. Rather

it’s Beatrice Miles going twelve hundred ditto in a taxi,

No Lewd Advances, No Hitting Animals, No Speeding,

on the proceeds of her two-bob-a-sonnet Shakespeare readings.

An image of my country. And would that it were more so.

No, sprawl is full-gloss murals on a council-house wall.

Sprawl leans on things. It is loose-limbed in its mind.

Reprimanded and dismissed

it listens with a grin and one boot up on the rail

of possibility. It may have to leave the Earth.

Being roughly Christian, it scratches the other cheek

and thinks it unlikely. Though people have been shot for sprawl.

Copyright © 2000 by Les Murray