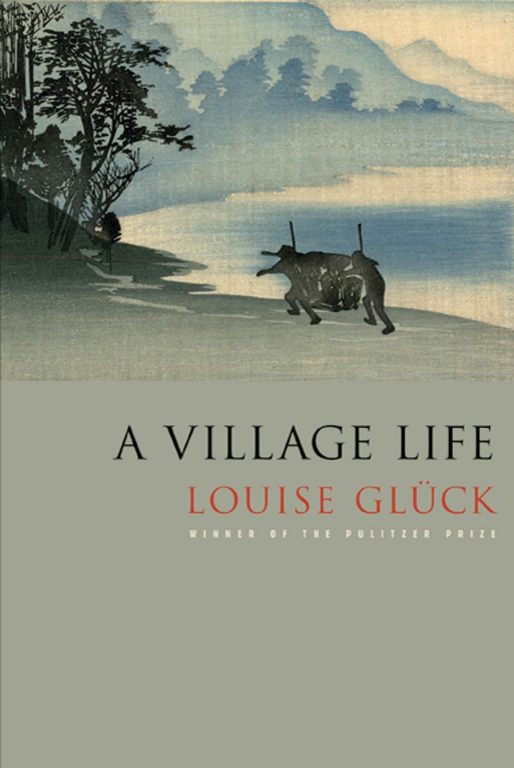

Louise Glück (1943-2023) was the author of numerous poetry books, including Winter Recipes from the Collective (2021); Faithful and Virtuous Night (2014), which won the National Book Award; Poems: 1962-2012 (2012), winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize; A Village Life (2009), which was a finalist for the International Griffin Poetry Prize, The Wild Iris (1992), which won the Pulitzer Prize; and Ararat (1990), which won the Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry from the Library of Congress.

In 2020, Glück was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for “her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.”

Her other awards include the Bollingen Prize, the Wallace Stevens Award, the Lannan Literary Award for Poetry, a National Humanities Medal, and a Gold Medal for Poetry from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She taught at Williams College, Yale University, Boston University, the University of Iowa, and Goddard College. We were saddened to learn of Louise Glück’s passing at the age of 80.

Judges’ Citation

In A Village Life, Louise Glück presents us with a choir of voices whose song enacts and contemplates our human quest for the very happiness that – as if instinctively – we refuse.

In A Village Life, Louise Glück presents us with a choir of voices whose song enacts and contemplates our human quest for the very happiness that – as if instinctively – we refuse. The result is a restlessness that seems never to leave us, as Glück suggests in ‘In the Café’: ‘It’s natural to be tired of earth./When you’ve been dead this long, you’ll probably be tired of heaven./You do what you can do in a place/but after a while you exhaust that place,/so you long for rescue.’ This clarity of wisdom everywhere punctuates these poems which, even as they concern restlessness, are cast in long lines shot through with imagery of pristine, archetypal simplicity producing a cinematic stillness; one thinks of the camera in a Bergman film. The tension between that stillness and the subject of restlessness produces a resonance that builds even as it shifts like thought, like the light and dark that constantly fall across the village itself. As for the village, it seems ultimately to be the human spirit itself, replete with hopes realized and dashed, dreams without resolution, memories to which we return, often enough, to our regret, and too late. A Village Life is a tour-de-force of imagination and artistry, and shows Glück putting her considerable powers to new challenges.

Selected poems

by Louise Glück

Like a child, the earth’s going to sleep,

or so the story goes.

But I’m not tired, it says.

And the mother says, You may not be tired but I’m tired—

You can see it in her face, everyone can.

So the snow has to fall, sleep has to come.

Because the mother’s sick to death of her life

and needs silence.

Copyright © 2009 by Louise Glück, A Village Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

First Snow

My body, now that we will not be traveling together much longer

I begin to feel a new tenderness toward you, very raw and unfamiliar,

like what I remember of love when I was young—

love that was so often foolish in its objectives

but never in its choices, its intensities.

Too much demanded in advance, too much that could not be promised—

My soul has been so fearful, so violent:

forgive its brutality.

As though it were that soul, my hand moves over you cautiously,

not wishing to give offense

but eager, finally, to achieve expression as substance:

it is not the earth I will miss,

it is you I will miss.

Copyright © 2009 by Louise Glück, A Village Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Crossroads

A cool wind blows on summer evenings, stirring the wheat.

The wheat bends, the leaves of the peach trees

rustle in the night ahead.

In the dark, a boy’s crossing the field:

for the first time, he’s touched a girl

so he walks home a man, with a man’s hungers.

Slowly the fruit ripens—

baskets and baskets from a single tree

so some rots every year

and for a few weeks there’s too much:

before and after, nothing.

Between the rows of wheat

you can see the mice, flashing and scurrying

across the earth, though the wheat towers above them,

churning as the summer wind blows.

The moon is full. A strange sound

comes from the field—maybe the wind.

But for the mice it’s a night like any summer night.

Fruit and grain: a time of abundance.

Nobody dies, nobody goes hungry.

No sound except the roar of the wheat.

Copyright © 2009 by Louise Glück, A Village Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Abundance

It’s very dark today; through the rain,

the mountain isn’t visible. The only sound

is rain, driving life underground.

And with the rain, cold comes.

There will be no moon tonight, no stars.

The wind rose at night;

all morning it lashed against the wheat –

at noon it ended. But the storm went on,

soaking the dry fields, then flooding them –

The earth has vanished.

There’s nothing to see, only the rain

gleaming against the dark windows.

This is the resting place, where nothing moves –

Now we return to what we were,

animals living in darkness

without language or vision –

Nothing proves I’m alive.

There is only the rain, the rain is endless.

Copyright © 2009 by Louise Glück, A Village Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Solitude

- Louise Glück on Poetry, Aging and a Surprise Nobel Prize New York Times

- Nobel Speech

- Colm Tóibín in conversation with Louise Glück New York Public Library