Luljeta Lleshanaku was born in Elbasan, Albania. She is the author of seven books of poetry in Albanian. Book length translations of her work into other languages include Antipastoral (Italy, 2006), Kinder der natur (Austria, 2010), Dzieci natury (Poland, 2011), and Lunes en Siete Dias (Spain, 2017). She has won several prestigious awards for her poetry, including PEN Albania 2016, and the International Kristal Vilenica Prize in 2009. In 2012 she was one of two finalists in Poland for their European Poet of Freedom Prize.

Judges’ Citation

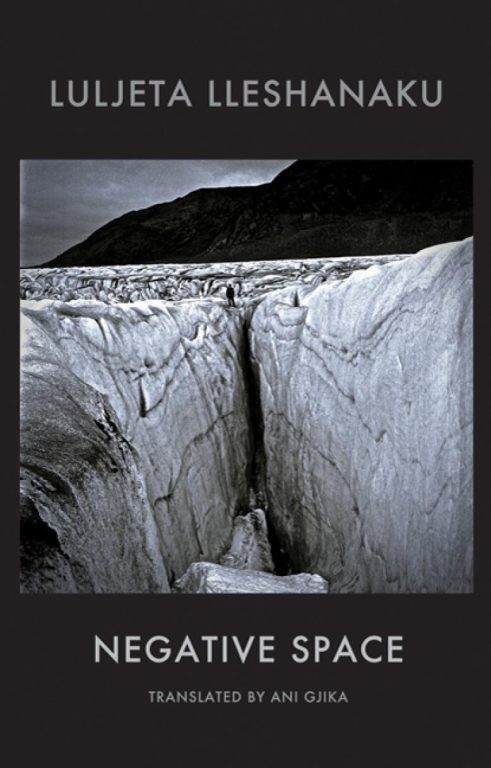

With a lesser known original language, the more precious the gift of translation! Luljeta Lleshanaku’s Negative Space offers a rare glimpse into contemporary Albanian poetry.

With a lesser known original language, the more precious the gift of translation! Luljeta Lleshanaku’s Negative Space offers a rare glimpse into contemporary Albanian poetry. Effortlessly and with crisp precision, Ani Gjika, herself a poet, has rendered into English, not only the poems in Negative Space, but also the eerie ambience which resonates throughout the book, the deep sense of impermanence that is one of the many consequences of growing up under severe political oppression. ‘Negative space is always fertile.’ Opening trauma’s door, we’re met by a tender and intelligent voice with stories illuminating existence in a shared humanity, thus restoring dignity. In a world fractured by terror and violence, Lleshanaku’s poetry is infinitely exciting, soothing us, its citizens.

Selected poems

by Luljeta Lleshanaku

Look what we have here:

some books bought with a little savings,

as if land purchased for a house

that you might never build. Plato, Hegel, The Marxist Movement,

heavy cloth covers. Sideways, behind Aristotle, rests Art Nouveau,

like the head of a woman nodding off on the train,

your shoulder still out of politeness.

Books in foreign languages, bought with the last change

from shops you’ll never visit again:

Tarkovsky’s Techniques, exchanged for five food vouchers;

Bergman, Hitchcock, Luis Buñuel reveal only part of the wall,

each the end of a misleading path inside a pyramid.

African Masks, Aztec Culture, Egyptian Gods

all bought on a rainy day perhaps, as an excuse to stay indoors.

And again the visual arts albums

labelled Ars in Latin like medicinal bottles

that camouflage a bitter taste.

Hugo, Turgenev, Stendhal . . .

relics of first love, second love, of . . .

A dark empty space

and further, Dostoyevsky’s White Nights

with its green irony on the cover that says,

‘Throw a coat over your shoulders first . . .’

And lower, Gaudí and other architectural books . . .

A smooth transition between what you wanted

and what you were able to attain.

Encyclopaedias, temples without roofs.

Shakespeare exchanged for a noisy Soviet radio.

Poetry books: thin, sly, bought at discounted prices,

breaking apart like crumbled bread thrown at swans in the park.

The only ones arranged horizontally

are The Erotic Art of the Middle Ages, The Ethical Slut, and Tropic of Cancer —

easy to find when feeling around in the dark,

like slippers under the bed.

In a corner, the holy books, the Gospels.

They’ve arrived here by themselves — you didn’t spend a cent to buy them.

Each volume almost never opened. How can you believe something

that doesn’t ask for anything in exchange?

And on the very bottom, The Barbarian Invasion, history, science . . .

Time to read with glasses. Linear reading. Andropause.

To show someone your library is an intimate gesture,

like giving him a map, a tourist map of the self

marked with the museums, parks, bridges, galleries, hotels, churches, subway . . .

and the graveyards that appear regularly

at the edges of every town, at the beginning of every epoch.

Copyright © 2018, Ani Gjika translated from the Albanian written by Luljeta Lleshanaku, Negative Space, Bloodaxe Books

This Gesture

the Albanian written by Luljeta Lleshanaku

3

Your body throws you under the bus; your body betrays you.

Your body is simply water and carbon.

I was 17 one morning in my prison cell

when after a night of delirium, running a 107-degree fever

caused by bronchopneumonia,

I woke up drenched in my own urine.

I was neither a child nor a man any more.

Then in the labour camp, out in the marsh,

I saw the theologian gathering rotten bits of cigarettes,

smelling the butts, trying to take a single drag.

But when I saw the former Sorbonne professor,

secretly digging through the trash and pick up a piece of watermelon rind,

which he then wiped on his pants and swallowed whole without chewing,

I knew I witnessed five thousand years of civilisation

extinguished in one moment.

Of course, it’s always the fault of the witness,

the wrong eyes at the wrong place.

Without a witness we wouldn’t even have crematoriums

and only white fumes would leak out of history’s nostrils.

4

He had such dignity, the old man who hung himself

(rejected here on earth and now also in heaven),

his bare feet like a saint’s, his body a frozen planet

revolving one last time around itself,

his head drooped to one side,

as if he were refusing to witness even his own death …

But it didn’t end here; they plucked out his gold teeth

as if removing three generations of his history.

Declassed, disgraced, even among the dead.

How can a toothless man protect himself at the last Judgement?

How could he formulate his arguments?

The dead would laugh; angels would shake their heads.

And so he too would be forgotten.

Simply water and carbon like everyone else.

The living went back to work, eyes cast down as if at their own funeral.

The whips against their joints and back

gave them no time to think much.

You can’t be last in line – this was the goal,

morning to night.

But where was our country at that moment? Where was Caesar?

From Negative Space by Ani Gjika, translated from the Albanian by Luljeta Lleshanaku

Copyright © Luljeta Lleshanaku 2012, 2015, 2018

Translation © Ani Gjika 2018

from Water and Carbon

the original written by Luljeta Lleshanaku

After the celebrations,

people, TV channels, telephones,

the year’s recently corrected digit

finally fall asleep.

Between the final night and the first dawn

a jagged piece of sky

as if viewed from the open mouth of a whale.

Inside her belly and inside the belly of time,

there’s no point worrying.

You glide gently along. She knows her course.

Inside her, you are digested slowly, painlessly.

And if you’re lucky, like Jonah,

at some point she’ll spit you out on dry land

along with heaps of inorganic waste.

Everything sleeps. A sweet hypothermic sleep.

But those few still awake

might hear the melancholy creaking of a wheelbarrow,

someone stealing stones from a ruin

to build new walls just a few feet away.”

Copyright © 2018

January 1, Dawn

the Albanian written by Luljeta Lleshanaku

- Luljeta Lleshanaku profile Poetry Foundation

- Luljeta Lleshanaku and Ani Gjika on Negative Space Poetry Society of America

- Luljeta Lleshanaku: Words Are Delicate Instruments Guernica