Poet and translator Michael Hofmann was born in Freiburg, West Germany in 1957. The son of the German novelist Gert Hofmann, his translation of his father’s novel The Film Explainer won The Independent’s Foreign Fiction Prize in 1995. He grew up in England and attended schools in Edinburgh and Winchester. Hofmann did his postgraduate studies at the University of Regensburg and Trinity College, Cambridge from 1979 to 1983. Since 1983 he has worked as a freelance writer, translator and reviewer.

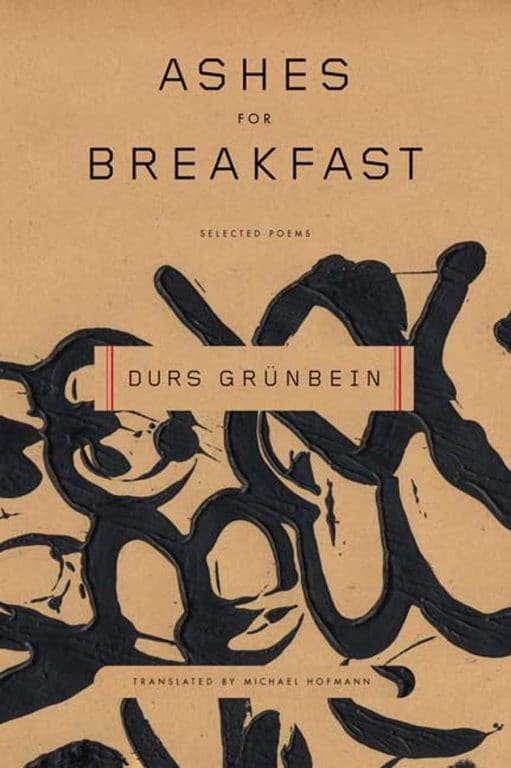

Hofmann has translated work by Bertolt Brecht, Joseph Roth, Patrick Süskind, Herta Mueller and Franz Kafka. He has twice won the Schlegel-Tieck Prize (Translator’s Association), first in 1988 for his adaptation of The Double Bass by Patrick Süskind (1987) and again in 1993 for his translation of Wolfgang Koeppen’s Death in Rome (1992). Ashes for Breakfast has been shortlisted for the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize. Hofmann’s published poetry includes Nights In the Iron Hotel (1983), which won the Cholmondeley Award; Acrimony (1986), which won the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize; Corona, Corona (1993) and Approximately Nowhere (1999). In 1994, Hofmann co-edited After Ovid: New Metamorphoses with James Lasdun, which included contributions by Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney. Behind the Lines: Pieces on Writing and Pictures, a collection of Hofmann’s reviews from the Times Literary Supplement, the London Review of Books, The New York Times and The Times was published in 2001. He lives in London.

Judges’ Citation

Michael Hofmann’s translations are live-action engagements of one poet with another – of languages reacting, competing, consoling and teasing – and propose new answers to old questions about whether poetry can travel this well or at all.

Born in Dresden, a ‘deathtrap for angels’, Durs Grünbein is the most significant poet to have emerged from the old East. His poems have a remarkable quality of contemplation, which enables them to shrug off pathos and irony, and so to reveal their personal and political depths. Unromantic, contained, but always moving and moved, he is ever alert to history’s ‘sudden nearness’ and brings it to us as mirror, window and trapdoor. Michael Hofmann’s translations are live-action engagements of one poet with another – of languages reacting, competing, consoling and teasing – and propose new answers to old questions about whether poetry can travel this well or at all.

Selected poems

by Michael Hofmann

9

Now listen to this: in the obituary they wrote about me

In my lifetime, they said I was so sweet-natured

That they wanted to keep me as a pet.

It makes me ill to hear them drooling

About my loyalty, my affection, my trustworthiness around children.

Tripe! There’s a term for everything alien.

Looks as though time has caught up with me.

And my voice is swimming in the confession:

“I was half zombie, half enfant perdu …”

Perhaps eventually space gulped me down

Where the horizon closes up.

My double can look after me from here on in.

My orneriness is puked out, plus the question:

Do pets have lighter brains?

Copyright © 2005 by Durs Grunbein / Translation and preface 2005 by Michael Hofmann

from Portrait of the Artist as a Young Border Dog (Not Collie)

the German written by Durs Grünbein