Priscila Uppal is the author of four previous collections of poetry: How to Draw Blood From a Stone (1998); Confessions of A Fertility Expert (1999); Pretending to Die (2001); Live Coverage (2003) and a novel, The Divine Economy of Salvation (2002), which was published by Doubleday in Canada and Algonquin Books of Chapel Hall in the United States, and translated into Dutch and Greek. Her poetry has been translated into Korean, Croatian, Latvian, and Italian. She is professor of Humanities at York University and co-ordinator of York’s Creative Writing Program. Priscila Uppal lives in Toronto, Canada.

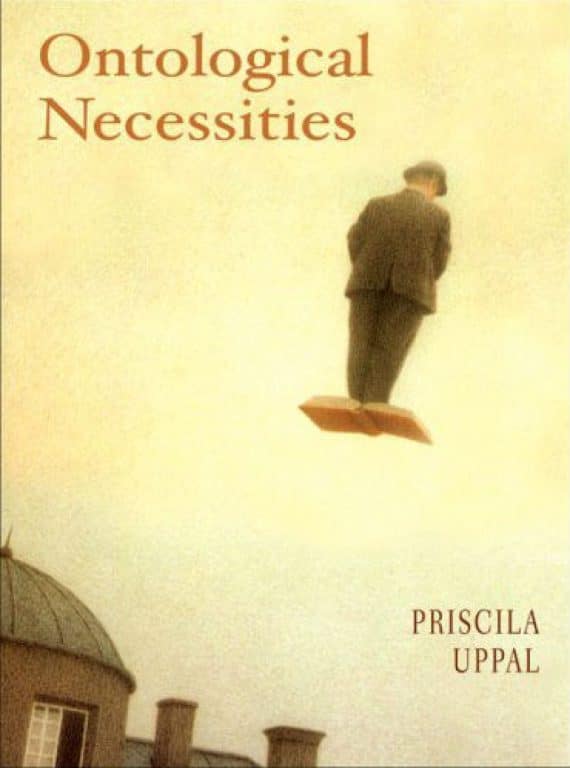

Priscila Uppal’s vibrant energy imbued everything from her academic and literary work to how she engaged with colleagues, students, friends and readers. Her poetry collection Ontological Necessities graced the Griffin Poetry Prize shortlist in 2007, and she supported and brightened every Griffin occasion she could attend. At the news of her passing on September 5, 2018, our deepest sympathies go to her loved ones, and to all who admired and connected with her work.

Judges’ Citation

Uppal has done the rare and difficult thing: she has brought a brand new voice to poetry.

Who are you? One of Priscila Uppal’s poems keeps asking itself. Are you the oyster shell of the new millennium, the sundial waitress in her two-bit automobile with a license to fish, the wristwatch of the nation, the woman’s shelter of the soul? The poems in Ontological Necessities are all that and much more. Audacious, irreverent, funny and, at the same time, deeply serious, they explore our notions of identity and various other conventions we live by striving to see through the lies. The ever-present horrors of our age; the injustice, the violence, the abuse and slaughter of the innocent, are almost always present. Uppal is a political poet who sounds like no other political poet, someone bound to get in trouble in every political system in the world. Her subject matter tends to be dark, but her telling of it is exhilarating. Every poem in her book comes as a surprise, and that includes the free translation of the Anglo-Saxon poem ‘The Wanderer’ with which the book concludes, and which in her version deals with the Iraq war and the fate of people displaced by such calamities. Uppal has done the rare and difficult thing: she has brought a brand new voice to poetry.

Selected poems

by Priscila Uppal

Long enough since the genre was popular

we’ve forgotten what to call it: weird mix of quotes and collectibles, private

thoughts and uncensored meditations in brief, like locks of hair and

child height charts of your considerations

and ponderings. An abandoned art, you practise it with care: each quote

equal to the other, simple entries like coordinates of unmarked

appearances

in the sky – twenty years, over

8,000 days – the weather is “what you make of sunshine,” and only

women “can

make a man successful,” haven’t you heard

“God is the messenger, and we are all brothers and sisters,” organizations

of hate “must be fought with the ultimate crest: humanity,” and you

note a quote with a love reserved

for precision and the unattained, and I

suspend like cracked meteors in the ether

of your common message: go to bed, what is truly important in this world

has already been said.

“When people deserve love the least

is when the need it the most,” we are the axis

of cliche, “like mother like daughter,” sign your name

on this one before I turn out the light

and resume my interrupted prayer.

Copyright © 2006 by Priscila Uppal

Common Book Pillow Book

Absolutely no angels in this death poem.

Half-baked poets offer angels for consolation

the way neighbours offer fruitcake at Christmas.

Absolutely no talk of Christmas in this death poem.

Resurrection went out with yesterday’s trash and

holy stars and wise men appear on hockey jerseys.

Absolutely no wise men in this death poem.

Wise men have never made dying understandable.

They’ve drawn no pie charts or graphs for the soul.

Absolutely no mention of souls in this death poem.

THe soul is not a ship, or a bird, or a flag, or a flower.

We have no power of attorney over it, no death connection.

Absolutely no mention of death in this death poem.

Angels are listening and the wise men are sketching.

Look at where all these souls are headed and tell no one.

Copyright © 2006 by Priscila Uppal

No Angels in This Death Poem

According to Freud’s observations and analysis of his nephew fantasy-making with a shoe, the fort-da game is the necessary foundational basis by which a child can rightfully count on a parent who leaves for work or an office party or a trip to the Bahamas with her younger lover to eventually return.

The child, controlling the outcome, sees that through simple will and aggression he can force the shoe to go, then facilitate retrieval whenever he so desires. This, according to Freud, makes it easier for the child to accept separation of all kinds. Fort-da is mourning play.

Hence, in tragedies, shoes play important roles. Actors must think carefully about where to step. Frequently, prints are drawn in light chalk on the stage. No one likes to share a pair. Letters are pulled from their lips, as are knives. When boots find their mark, victims claim the soles.

Children must be encouraged to play fort-da. Freud said so, and he had very healthy relationships. For those of you whose parents have left and never returned, you happen to be screwed, psychologically speaking. Perhaps, as in the most successful tragedies, you should seek revenge.

Copyright © 2006 by Priscila Uppal

On the Psychology of Crying Over Spilt Milk

Sorry, Sirs and Madams, I forgot to clean up after myself

after the unfortunate incidents of the previous century.

How embarrassing; my apologies. I wouldn’t advise you

to stroll around here without safety goggles, and I must insist

that you enter at your own risk. You may, however, leave

your umbrella at the door. Just keep your ticket.

We expected, of course, to have this all cleared away by the time

you arrived. The goal was to present you

with blue and green screens, whitewashed counters.

Unforeseen expenses.

Red tape.

So hard to find good help these days.

But, alas, excuses. Perhaps you will appreciate

the difficulties I’ve faced in providing you a clean slate.

If you step into a hole, Sirs and Madams, accept the loss

of a shoe or two. Stay the course.

Progress is the mother of invention. Here: take my hand.

Yes, that’s right. You can return it on the way back.

Copyright © 2006, Priscila Uppal, Ontological Necessities, Exile Editions