Raymond Antrobus was born in Hackney, London, England to an English mother and a Jamaican father. He is the recipient of fellowships from Cave Canem, Complete Works III, and Jerwood Compton Poetry. He is one of the world’s first recipients of an MA in Spoken Word Education from Goldsmiths, University of London. Antrobus is a founding member of Chill Pill and the Keats House Poets Forum. He has had multiple residencies in deaf and hearing schools around London, as well as Pupil Referral Units. In 2018 he was awarded the Geoffrey Dearmer Award by the Poetry Society.

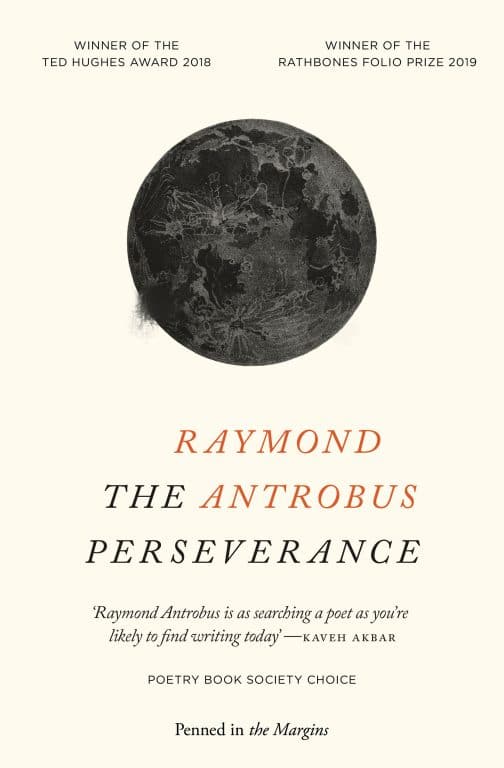

In addition to being shortlisted for the 2019 Griffin Poetry Prize, The Perseverance won the Ted Hughes Award, the Rathbones Folio Prize, the Somerset Maugham Award, and more.

Since The Perseverance, Raymond Antrobus has published, through Picador and Tin House, All The Names Given, a finalist for the 2020 T. S. Eliot Prize and the Costa Poetry Award, and Signs, Music, a finalist for the 2024 T. S. Eliot Prize. He lives in London, England.

Judges’ Citation

‘The truth is I’m not /a fist fighter,’ writes Raymond Antrobus, ‘I’m all heart, no technique.

‘The truth is I’m not /a fist fighter,’ writes Raymond Antrobus, ‘I’m all heart, no technique.’ Readers who fall for this streetwise feint may miss out on the subtle technique – from the pantoum and sestina to dramatic monologue and erasure – of The Perseverance. But this literary debut is all heart, too. Heart plus technique. All delivered in a voice that resists over-simple categorization. As a poet of d/Deaf experience, his verse gestures toward a world beyond sound. As a Jamaican/British poet, he deconstructs the racialized empire of signs from within. Perhaps that slash between verses and signs is where the truth is.

Selected poems

by Raymond Antrobus

after Danez Smith

I have left Earth in search of sounder orbits,

a solar system where the space between

a star and a planet isn’t empty. I have left

a white beard of noise in my place and many

of you won’t know the difference. We are

indeed the same volume, all of us eventually fade.

I have left Earth in search of an audible God.

I do not trust the sound of yours.

You wouldn’t recognise my grandmother’s Hallelujah

if she had to sign it, you would have made her sit

on her hands and put a ruler in her mouth

as if measuring her distance from holy.

Take your God back, though his songs

are beautiful, they are not loud enough.

I want the fate of Lazarus for every deaf school

you’ve closed, every deaf child whose confidence

has gone to a silent grave, every BSL user

who has seen the annihilation of their language,

I want these ghosts to haunt your tongue-tied hands.

I have left Earth, I am equal parts sick of your

oh, I’m hard of hearing too, just because

you’ve been on an airplane or suffered head colds.

Your voice has always been the loudest sound in the room.

I call you out for refusing to acknowledge

sign language in classrooms, for assessing

deaf students on what they can’t say

instead of what they can, we did not ask to be a part

of the hearing world, I can’t hear my joints crack

but I can feel them. I am sick of sounding out your rules –

you tell me I breathe too loud and it’s rude to make noise

when I eat, sent me to speech therapists, said I was speaking

a language of holes, I was pronouncing what I heard

but your judgment made my syllables disappear,

your magic master trick hearing world – drowning out the quiet,

bursting all speech bubbles in my graphic childhood,

you are glad to benefit from audio supremacy,

I tried, hearing people, I tried to love you, but you laughed

at my deaf grammar, I used commas not full stops

because everything I said kept running away,

I mulled over long paragraphs because I didn’t know

what a natural break sounded like, you erased

what could have always been poetry

You erased what could have always been poetry.

You taught me I was inferior to standard English expression –

I was a broken speaker, you were never a broken interpreter –

taught me my speech was dry for someone who should sound

like they’re underwater. It took years to talk with a straight spine

and mute red marks on the coursework you assigned.

Deaf voices go missing like sound in space

and I have left earth to find them.

Copyright © 2018

Dear Hearing World

Dad reads aloud. I follow his finger across the page.

sometimes his finger moves past words, tracing white space.

He makes the Moon say something new every night

to his deaf son who slurs his speech.

Sometimes his finger moves past words, tracing white space.

Tonight he gives the Moon my name, but I can’t say it,

his deaf son who slurs his speech.

Dad taps the page, says, try again.

Tonight he gives the Moon my name, but I can’t say it.

I say Rain-an Akabok. He laughs.

Dad taps the page, says, try again,

but I like making him laugh. I say my mistake again.

I say Rain-an Akabok. He laughs,

says, Raymond you’re something else.

I like making him laugh. I say my mistake again.

Rain-an Akabok. What else will help us?

He says, Raymond you’re something else.

I’d like to be the Moon, the bear, even the rain.

Rain-an Akabok, what else will help us

hear each other, really hear each other?

I’d like to be the Moon, the bear, even the rain.

Dad makes the Moon say something new every night

and we hear each other, really hear each other.

As Dad reads aloud, I follow his finger across the page.

Copyright © 2018 by Raymond Antrobus, The Perseverance, Penned in the Margins

Happy Birthday Moon

after Aaron Samuels

Some people would deny that I’m Jamaican British.

Anglo nose. Hair straight. No way I can be Jamaican British.

They think I say I’m black when I say Jamaican British

but the English boys at school made me choose: Jamaican, British?

Half-caste, half mule, house slave — Jamaican British.

Light skin, straight male, privileged — Jamaican British.

Eat callaloo, plantain, jerk chicken — I’m Jamaican.

British don’t know how to serve our dishes; they enslaved us.

In school I fought a boy in the lunch hall — Jamaican.

At home, told Dad, I hate dem, all dem Jamaicans — I’m British.

He laughed, said, you cannot love sugar and hate your sweetness,

took me straight to Jamaica — passport: British.

Cousins in Kingston called me Jah-English,

proud to have someone in their family — British.

Plantation lineage, World War service, how do I serve Jamaican British?

When knowing how to war is Jamaican British.

Copyright © 2018 by Raymond Antrobus, The Perseverance, Penned in the Margins

Jamaican British

My father had four children

and three sugars in his coffee

and every birthday he bought me

a dictionary which got thicker

and thicker and because his word

is not dead I carry it like sugar

on silver spoons

up the Mobay hills in Jamaica

past the flaked white walls

of plantation houses

past the canefields and coconut trees

past the new crystal sugar factories.

I ask dictionary why we came here –

It said nourish so I sat with my aunt

on her balcony at the top

of Barnet Heights

and ate saltfish

and sweet potato

and watched women

leading their children

home from school.

As I ate I asked dictionary

what is difficult about love?

It opened on the word grasp

and I looked at the hand

holding this ivory knife

and thought about how hard it was

to accept my father

for who he was

and where he came from

how easy it is now to spill

sugar on the table before

it is poured into my cup.

Copyright © 2018 by Raymond Antrobus, The Perseverance, Penned in the Margins