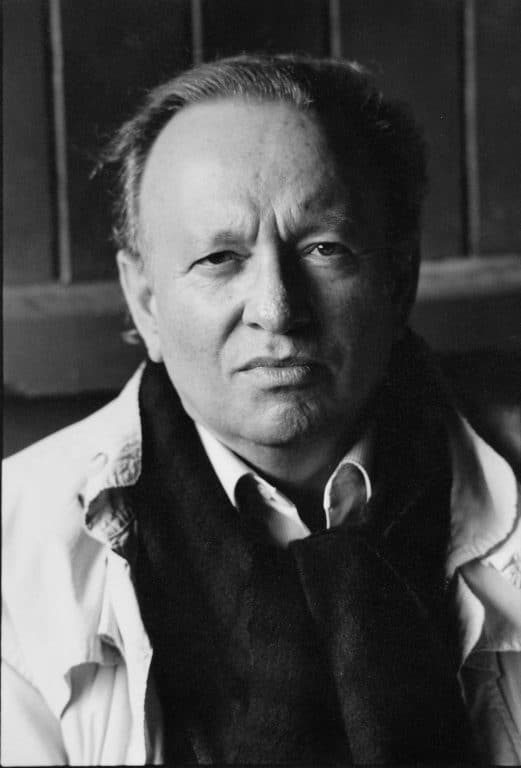

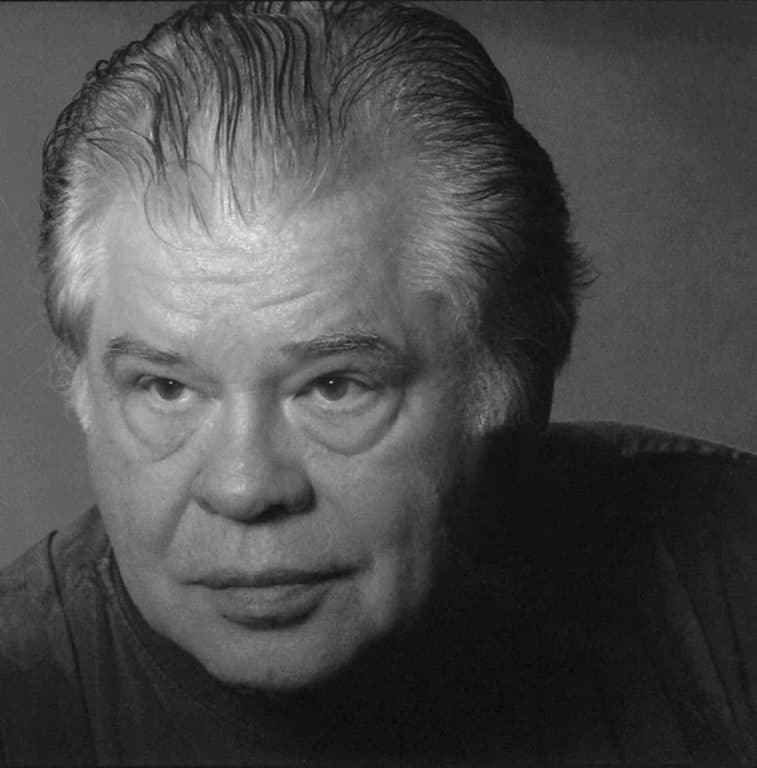

There is much to learn and explore in Durs Grunbein’s poem “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Border Dog (Not Collie)”, translated from German into English with sharp intensity by Michael Hofmann. We previously considered the first of the poem’s multiple parts, and now we’re going to scrutinize the ninth of its dozen sections.

The poem segment’s sardonic opening immediately leaves us wondering …

“Now listen to this: in the obituary they wrote about me

In my lifetime, they said I was so sweet-natured

That they wanted to keep me as a pet.”

Has someone or something indeed died? We’ve determined earlier in the poem that the unfortunate dog suggested here and throughout the poem metaphorically represents a severely frustrated narrator. Has a death notice been written for a dog, for the narrator or figuratively, for some aspect of the narrator’s existence? That the obituary, however it was composed, was written “in my lifetime” is a bit bewildering. Did the narrator see or imagine his obituary before he or some part of him died?

Is there a clue in …

“I was half zombie, half enfant perdu …”

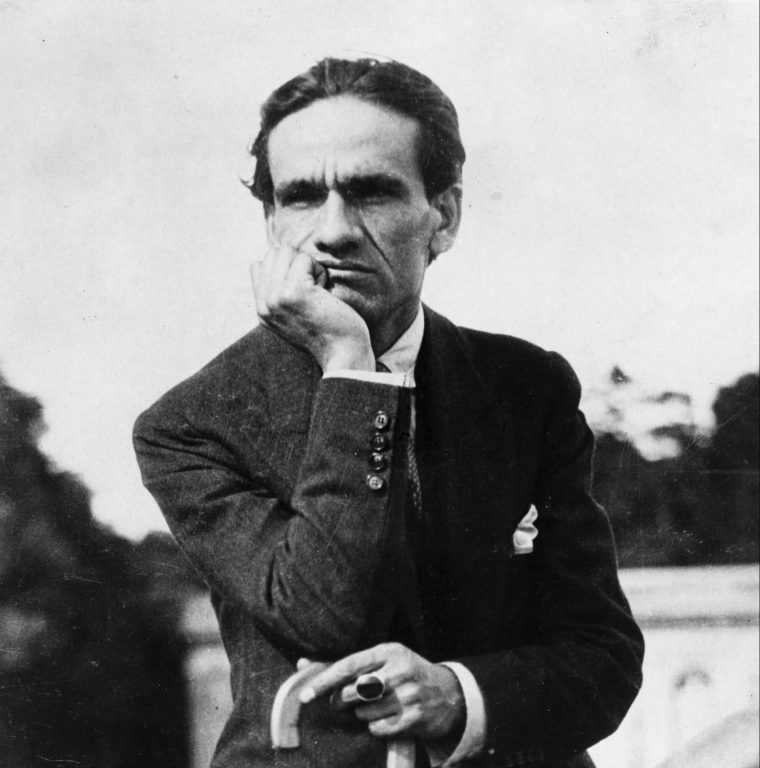

Some analyses of this poem connect it to “Enfant Perdu” by Heinrich Heine (1797-1856). Heine’s defiant tribute to liberty captures Grunbein’s narrator’s yearning. This translation of the Heine poem also makes a jolting reference to “brains” that has a strange and haunting echo here:

“Do pets have lighter brains?”

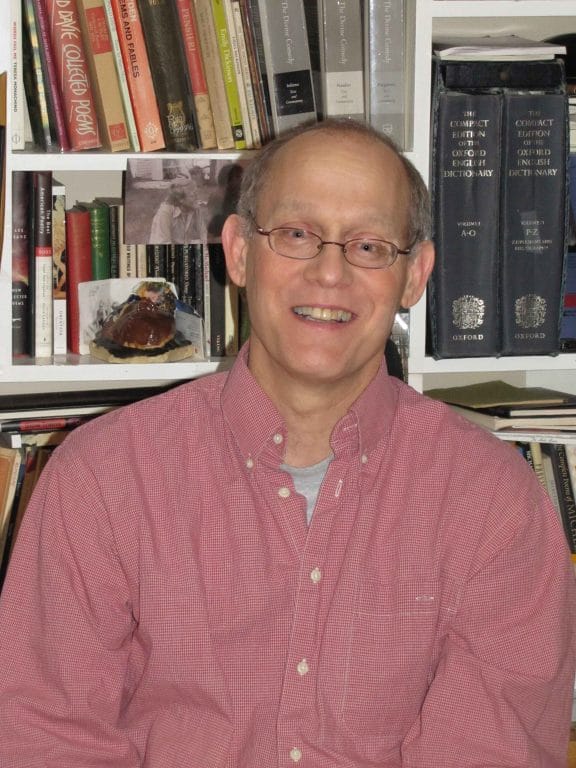

Whoever or whatever has died here, that a ghostly presence still has things to say from beyond is telling and memorable. This review of books featuring deceased narrators sums it up powerfully:

“Death’s portal opens in only one direction, but they are compelled to return, these revenants, some to watch, some to wait, some to want and want and not to have.”

As Hofmann’s translated words declare with dismissive chagrin (but maybe a molecule of hope, as something seems to survive):

“My double can look after me from here on in.”