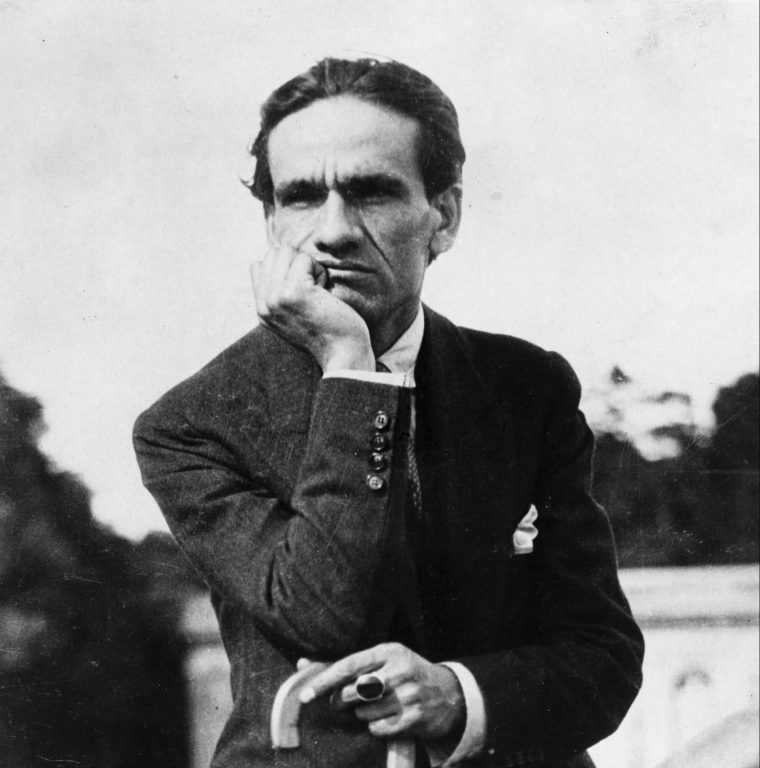

So striking is this poem from Matthew Rohrer’s 2005 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted collection A Green Light that the judges singled it out in their citation of the work. To be precise, they singled out the character who stars in this eponymous poem, and whose presence is felt throughout the collection.

Rohrer has adopted…

So striking is this poem from Matthew Rohrer’s 2005 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted collection A Green Light that the judges singled it out in their citation of the work. To be precise, they singled out the character who stars in this eponymous poem, and whose presence is felt throughout the collection.

Rohrer has adopted a persona in “The Adorable Little Boy” that, judged by that character’s words, offered directly and with no overt editorial intervention, might or might not strike the reader as endearing or appealing. The Academy of American Poets explains the use of persona in poetry:

“A persona poem is a poem in which the poet speaks through an assumed voice.

Also known as a dramatic monologue, this form shares many characteristics with a theatrical monologue: an audience is implied; there is no dialogue; and the poet takes on the voice of a character, a fictional identity, or a persona. Because a dramatic monologue is by definition one person’s speech, it is offered without overt analysis or commentary, placing emphasis on subjective qualities that are left to the audience to interpret.”

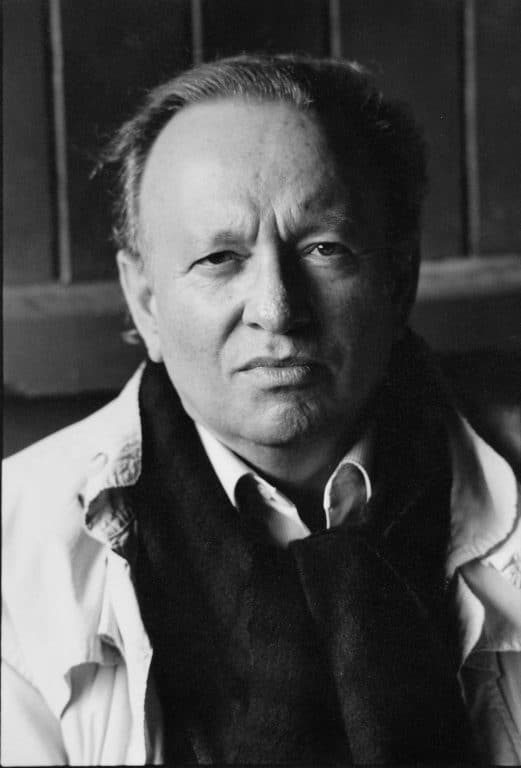

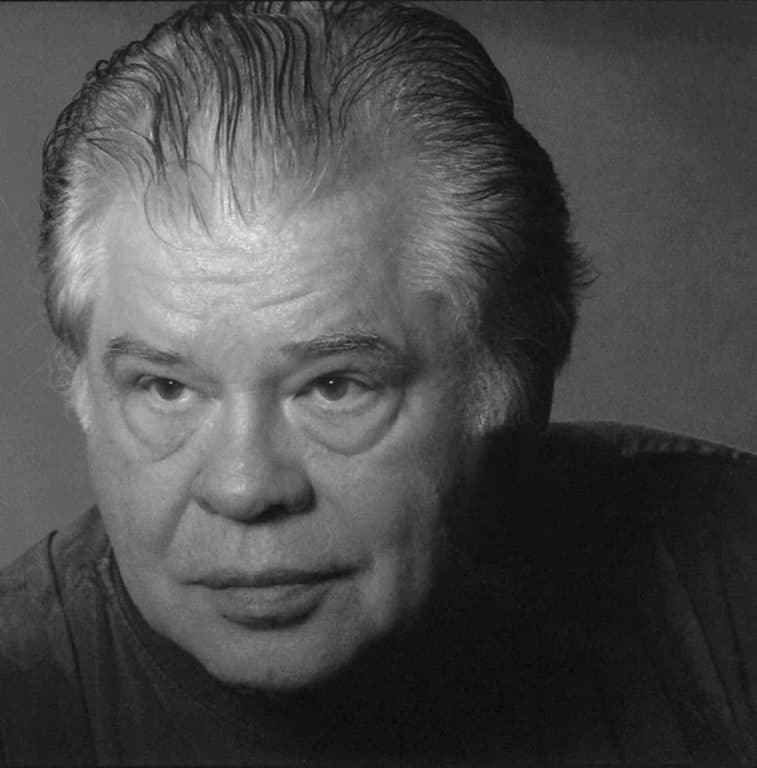

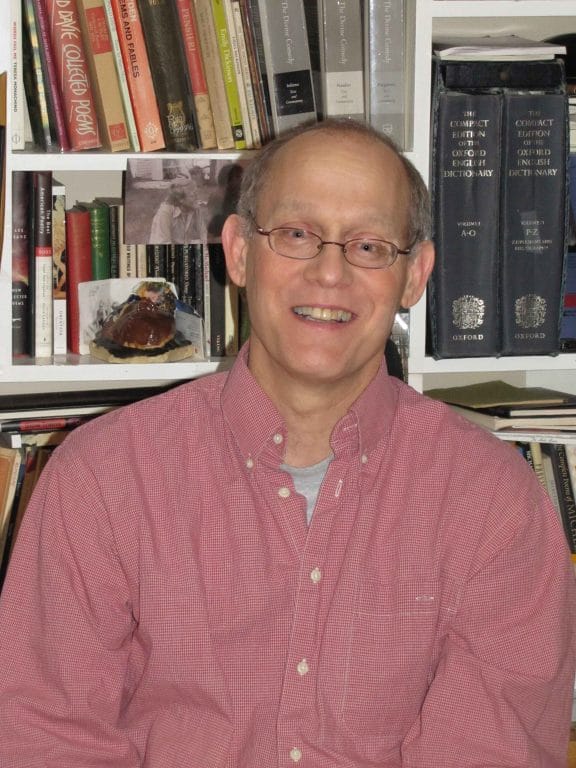

The Academy of American Poets goes on to present some interesting examples. We’ve touched on the use of persona in other Poem of the Week selections, including “Microscopic Surgery” by David W. McFadden, “Homage to Pessoa” by Frederick Seidel, “67” by Sarah Tolmie and “He thinks I should be glad because they” by Aisha Sasha John.

Taken a face value, then, we have before us an “Adorable Little Boy” with wrecked footwear, who is apparently tired of playing whatever this charming role is or was, and is now ready to drop the facade and admit sickness, cynicism and defeat. He wraps up his tenure in the role with some parting insults and insolence. Then he closes with the unexpectedly erudite “Pliny described trees that speak.” Non sequitur or not, he still wants us to admire him, doesn’t he?