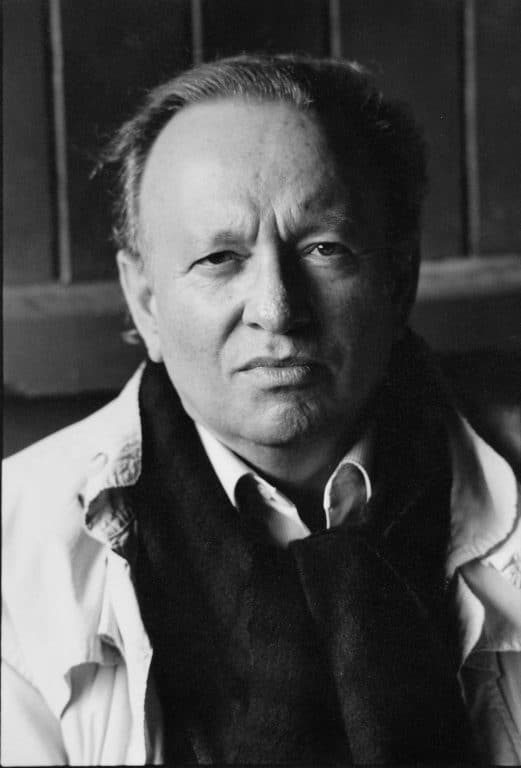

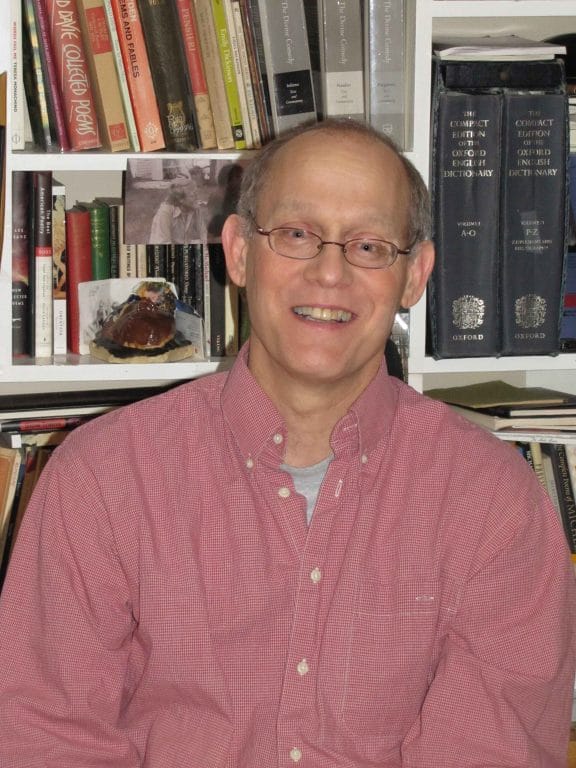

“Carl Phillips is a poet of the line and a poet of the sentence, both at once,” declares the judges’ citation for Phillips’ 2014 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted poetry collection Silverchest. The poem “Now Rough, Now Gentle” is an emphatic example of the poet’s prowess.

The poem’s opening line is brisk, verging on rough in…

“Carl Phillips is a poet of the line and a poet of the sentence, both at once,” declares the judges’ citation for Phillips’ 2014 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlisted poetry collection Silverchest. The poem “Now Rough, Now Gentle” is an emphatic example of the poet’s prowess.

The poem’s opening line is brisk, verging on rough in tone – you’re commanded to “never mind”. Hindsight is damned as rife with uselessness, regret and death are blithely paired, the only thing that is fresh or lovely here is also stolen, something is stirring, but maybe failing to stir … all of it sounds more than tinged with bitterness, and that is rough. That is, the dictionary meaning of “rough” as in harsh or, referencing the poem’s title, not gentle.

“Rough” can also mean preliminary, not finished in form. As the poem’s first sentence unspools, containing within it fragments of other sentences, much is posited as the words tumble forth, but the final phrase “who can say?” leaves things unfinished, not concluded. Wending through that sentence, the reader comes to understand that “rough” and “gentle” can denote and connote so many types of qualities, forms of interaction and so on.

The poem’s closing sentence, covering two and one-half lines, is tender, decidedly gentle even as its wistfulness retains a hint of the poem’s initial bitterness. In fact, this 16-line poem is only comprised of two sentences. Indeed, what the Griffin Poetry Prize judges zeroed in on first and foremost in their commentary on Phillips’ work is displayed perfectly in this poem, as it runs the gamut from sardonic to transcendent.

There is, by the way, an interesting echo of the poem’s title in this description of part of Phillips’ artistic process, where he reveals that he reads his work in progress aloud.

“I do read the poems aloud, yes — not while writing, as much, but in the revision stage. I want to test for where things are too rough, or aren’t rough enough, where they fall into patterns of sound and whether or not those are meaningful or distracting patterns.”

Whichever meaning or meanings of “rough” he’s referring to, the poet is clearly conscious of the rough and the gentle as he crafts his poetry.